DIRECTOR'S REVIEW: Bumper Cars and Demolition Derby

On one of those exquisite spring evenings that Kyiv can offer up, I found myself wandering around the Ukrainian capital with a couple of former Kennan Institute scholars. This was a moment of intense political "crisis" in Ukraine, during which raucous demonstrators had peacefully surrounded the headquarters of the security forces just the day before. The evening's fare reflected the city's mood. We set out first for a Party of Regions rally on the Maidan—where we just missed hearing Prime Minister Yanukovych speak—before we walked a few hundred yards down the Khreshchatyk through a flimsy and relaxed police line to an even larger "meeting" of Our Ukraine supporters listening to Yulia Tymoshenko hold forth. After this high political excitement, we strolled around the fragrant streets of Kyiv in bloom. Suddenly, we happened upon an encounter between two groups of political opponents. Tymoshenko supporters decked out in orange were helping out-of-town Yanukovych supporters sporting blue and yellow find the entrance to the metro.

On one of those exquisite spring evenings that Kyiv can offer up, I found myself wandering around the Ukrainian capital with a couple of former Kennan Institute scholars. This was a moment of intense political "crisis" in Ukraine, during which raucous demonstrators had peacefully surrounded the headquarters of the security forces just the day before. The evening's fare reflected the city's mood. We set out first for a Party of Regions rally on the Maidan—where we just missed hearing Prime Minister Yanukovych speak—before we walked a few hundred yards down the Khreshchatyk through a flimsy and relaxed police line to an even larger "meeting" of Our Ukraine supporters listening to Yulia Tymoshenko hold forth. After this high political excitement, we strolled around the fragrant streets of Kyiv in bloom. Suddenly, we happened upon an encounter between two groups of political opponents. Tymoshenko supporters decked out in orange were helping out-of-town Yanukovych supporters sporting blue and yellow find the entrance to the metro.

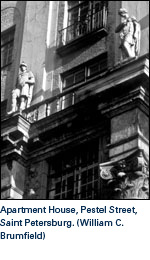

A week later I was meeting in St. Petersburg with a group of former Kennan Institute scholars who had been beaten badly at a political rally a few days before. The fragile working relationships between opposition groups and local security forces had broken down suddenly when special forces troops from neighboring regions were unleashed on the crowd. There would be no loud but orderly demonstrations confronting security forces in the Northern Palmyra; no home-grown activists showing out-of-towners the way to the metro. Political life in Russia was becoming a blood sport.

Ukraine and Russia have been on different trajectories for some time, presenting an ideal setting for comparative social science research. Ukraine is a country visibly divided by fractures and fissures which run through the entire social landscape. Politicians are like bumper cars, clumsily careening toward one another in an amusement park before bouncing off more or less unharmed only to come crashing together yet again. Society sorts out its own coping mechanisms every day on the streets so as not to allow divisions to overshadow an increasingly good life.

Russian politics, on the other hand, resemble the American automobile sport of demolition derby, in which drivers of old, beat-up cars viciously crash together with increasing violence until only one victor is left to ramble around the field. The good life in Russia seems reserved for the strong.

Russian reality is more complex than its ever-more controlled political life might suggest, with very real divisions and contrasts existing across the sprawling Russian Federation. The social science question posed by contemporary Russia is more difficult than that presented by contemporary Ukraine. Ukraine's complexities are open for all to see. Russia's contradictions are hidden behind layers of obfuscation. No observers mistake Ukraine for the Soviet Union; analysts talk and write about the return of Soviet political practices in Russia every day. This perspective—which, at times, appears to be shared by the Russian political class—is misplaced.

While today's Russian Federation unquestionably has more strategic and economic assets than the Russian Federation of a decade ago, Russia remains a smaller country than the USSR in every respect. The boundaries—physical and mental—that so sharply demarcated the Soviet Union from the world outside have been shattered. Large numbers of Russians live in daily contact with the outside world in contrast to their Soviet predecessors, who lived in not-so-splendid isolation. The demographic and health crises that helped to bring about the end of the Soviet Union continue to eviscerate Russian society; the challenges of configuring a 21st century educational system seem more daunting than the Soviet goal of training people for their one job of a lifetime. Most importantly, today's Russia lacks an encompassing ideology that seeks human transformation at home and abroad.

Russia is changing in positive and dynamic ways. New paths for social mobility are opening up, an emergent middle class is sorting out its place in the universe, and cultural life is enriched by society's innate incongruities and contradictions. Russia continues to produce exceptional human beings who add fresh insight into the human condition and great beauty to human existence.

Russia is changing in positive and dynamic ways. New paths for social mobility are opening up, an emergent middle class is sorting out its place in the universe, and cultural life is enriched by society's innate incongruities and contradictions. Russia continues to produce exceptional human beings who add fresh insight into the human condition and great beauty to human existence.

Ukraine and Russia present profound intellectual and policy challenges to all who seek to understand what is happening in each country. No easy model imposed from abroad or from within can explain the complexities of either society. Both countries are societies that are much more than their political systems.

Integrating the Contradictions of Eurasian Life

In 1954, George F. Kennan wrote that "we must be gardeners and not mechanics in our approach to world affairs. We must come to think of the development of international life as an organic and not a mechanical process. We must realize that we did not create the forces by which this process operates. We must learn to take these forces for what they are and to induce them to work with us and for us by influencing the environmental stimuli to which they are subjected, but to do this gently and patiently, with understanding and sympathy, not trying to force growth by mechanical means, not tearing the plants up by the roots when they fail to behave as we wish them to." In other words, we need to think holistically about the complexities of the world around us, bringing together the insights of multiple disciplines and intellectual traditions, and combining the insights of abstract theory with those of everyday life.

The Kennan Institute's offices and networks of scholars have been working over the past year to develop this multi-disciplinary approach. Particular attention has been given to three areas of study that returned to prominence after the end of the Soviet Union: religious diversity, migration and tolerance, and modernization. All three topics have been consistent features of human experience throughout history, and each theme deserves concentrated study in the post-Soviet context.

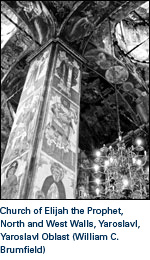

To the surprise of many, the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 revealed a diverse, multicultural, multi-confessional population living in its ruins. Religious beliefs and practices of many forms had persisted even while churches, synagogues, mosques, and other religious institutions were summarily repressed and destroyed. This religious diversity—and the newly dynamic and sometimes global nature of religious movements within it—is of profound importance in the region today, particularly as people continue to add new meanings to their lives after the collapse of a dominant political ideology with totalitarian ambitions.

Over the past several years, the Kennan Institute has initiated a number of activities supporting academic analysis of the diverse religious practices and beliefs visible throughout the former Soviet Union. The Institute's Washington, D.C. office is coordinating the research of its resident scholars, the deliberations of smaller working groups and larger public lectures and conferences, and is preparing publications which explore the religious dimension of contemporary life in Russia, Ukraine, and other post-Soviet countries. These activities draw on the knowledge of American and international specialists, promoting an active conversation about the meaning and significance of religious diversity throughout the region.

Over the past several years, the Kennan Institute has initiated a number of activities supporting academic analysis of the diverse religious practices and beliefs visible throughout the former Soviet Union. The Institute's Washington, D.C. office is coordinating the research of its resident scholars, the deliberations of smaller working groups and larger public lectures and conferences, and is preparing publications which explore the religious dimension of contemporary life in Russia, Ukraine, and other post-Soviet countries. These activities draw on the knowledge of American and international specialists, promoting an active conversation about the meaning and significance of religious diversity throughout the region.

Another process affecting international affairs is the enormous rise in the number of transnational migrants in the world. According to the United Nations, there are currently 185 million people living in countries other than those of their birth, up from 80 million people three decades ago. Migration is an especially pressing issue for the countries of the former Soviet Union, in which large-scale international migration is a relatively new phenomenon. While the collapse of the Soviet state brought with it expanded freedom of movement, it also resulted in increased restrictions at many destination points for migrants, providing new administrative challenges.

The Kennan Institute has focused a great deal of attention on this growing policy issue. Along with lectures, workshops, working groups, and seminars held over the past several years at all three Kennan offices, the Kennan Kyiv Project has given special attention to the issue, sponsoring a number of activities intended to explore the scale and nature of migration, and of the social and official responses to the presence of migrants within the country.

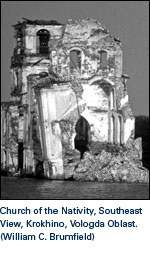

Along with religion and migration, the question of how to modernize a country successfully while minimizing the human and material costs has returned to Russia, Ukraine, and other countries in the region. As the socialist state dissolved into fragments, several realities became clear: markets were undernourished and undeveloped; property rights were not secure; Soviet infrastructure was disintegrating with little capital available to fix it; and demographic shifts lurched the countries toward crisis.

Along with religion and migration, the question of how to modernize a country successfully while minimizing the human and material costs has returned to Russia, Ukraine, and other countries in the region. As the socialist state dissolved into fragments, several realities became clear: markets were undernourished and undeveloped; property rights were not secure; Soviet infrastructure was disintegrating with little capital available to fix it; and demographic shifts lurched the countries toward crisis.

Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and the countries of Central Asia and the Caucasus face similar problems and opportunities for reform. How will they evaluate ideas about how society develops and improves? How will discourse about (and shifting attitudes toward) "democracy," "development," "globalization," and "the West" shape the reforms that these countries put into place? What can explain some of the backlash against these reforms—with countries such as Russia in particular decrying the violence with which markets opened and property went into the hands of oligarchs—and the political power of the evolving discourse on "the third way"?

For several years now, the Kennan Moscow Project has paid close attention to the question of whether or not there can be multiple forms of modernity. Is there, for example, such a thing as a "Russian-style" modernity in which Russians creatively interpret the accumulated experience of other countries while paying special attention to ethno-cultural, economic, social, and political factors? Is there a Ukrainian modernity or an Uzbek, Kazakh, or Georgian one? Some regional scholars have insisted that the specifics of the transformation processes in these regions should be considered within the framework of modernization theory. They adhere to the so-called "neo-modernistic" version of the theory, which argues that the rate, rhythm, and consequences of modernization differ greatly in various countries and spheres of social life. Others insist that modernization is a universal process that—as some schools of economists and political scientists have long insisted—cannot succeed in full form when the state interferes with processes such as the liberalization of markets. In the context of large-scale change at a global level, such competing views deserve a full and careful airing.

These and other issues continue to attract the attention of leading scholars and policymakers. The Kennan Institute will continue to focus on these core areas in the 2007–08 program year, in addition to the more traditional areas of inquiry, such as politics, economics, international relations, terrorism, and environmental issues.

These and other issues continue to attract the attention of leading scholars and policymakers. The Kennan Institute will continue to focus on these core areas in the 2007–08 program year, in addition to the more traditional areas of inquiry, such as politics, economics, international relations, terrorism, and environmental issues.

It remains to be seen whether the dominant pattern of politics in Russia and Ukraine will change significantly. Indeed, in light of the upcoming elections, Ukrainian and Russian politics most likely will continue to resemble bumper cars and demolition derbies, with the collateral damage scattered around the infield. To paraphrase George F. Kennan, however, we must be more than just mechanics when investigating these very public collisions. Other powerful social and economic forces are at work in Russia and Ukraine that merit persistent investigation and discussion. The Kennan Institute's focus on religious diversity, migration, and modernization—as well as other relevant themes—provides the necessary context to evaluate the ongoing political debates in Ukraine and Russia.

Blair A. Ruble

October 1, 2007

Related Links

Related Program

Kennan Institute

The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Russia and Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the surrounding region though research and exchange. Read more