Islamists Struggle to Match Religious Values to Politics

Mainstream Islamist movements across the Arab world have struggled to close the gap — or, really, even define the gap — between religious ideals and the mundane realities of everyday politics.

Shadi Hamid, a fellow at the Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World at the Brookings Institution’s Saban Center, is the author of Temptations of Power: Islamists and Illiberal Democracy in a New Middle East (Oxford University Press, 2014). In the following interview, Hamid examines Islamists’ attempts to matching religious values to mundane politics before and after the Arab uprisings.

What is the status of political Islam in the Arab world?

Mainstream Islamist movements across the Arab world have struggled to close the gap — or, really, even define the gap — between religious ideals and the mundane realities of everyday politics. They have few models on which to draw. Islamists were well aware of this, which is why there was an ambivalence, even an aversion, to power, to the extent that they would lose elections on purpose before the Arab spring.

The Algerian Islamist Abdel Kader Hachani captured the dueling sentiments of fear and ambition quite well, when, after the Islamic Salvation Front dominated the first round of elections in 1991, he warned a crowd of supporters: “Victory is more dangerous than defeat.” Similarly, in May 2011, I had a conversation with the Brotherhood’s Essam el Erian (left) , when he told me, “The people won’t accept an Islamist president.” That’s why I wanted to call the book “Temptations of Power.”

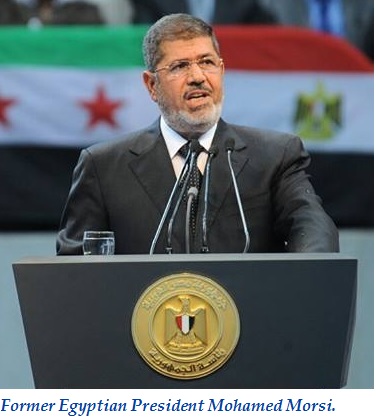

How did the Muslim Brotherhood react to Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi’s ouster in July 2013?

Brotherhood activists almost seemed relieved in the weeks after Morsi was ousted. I entered Rabaa al Adawiya Square to speak with el Erian after security forces had killed more than 140 Morsi supporters in two separate incidents. He was wearing a T-shirt and sweatpants and looked more calm and comfortable than before —despite the specter of bloodshed. Another Brotherhood official, Gehad al Haddad, told me he was “very much at peace.”

A weight – the weight of power – had been lifted. It was almost as if they had returned to a purer, more natural state: the state of opposition, something they had become used to over the course of more than eighty difficult years. Of course, this was before the August 14, 2013 Rabaa massacre, in which security forces killed some 600 pro-Morsi protestors and injured 2,000 others. They knew there would be bloodshed, but this was something else entirely. The sheer scale of violence was unprecedented.

Did any explicitly Islamist parties win elections in the Arab world before 2011? If so, what was their experience?

The Jordanian Brotherhood was the only democratically-elected Islamist group that participated in government before the Arab uprisings. For a brief period in 1991 – only six months – the Brotherhood controlled five ministries in a cabinet led by Prime Minister Mudar Badran. The group’s hawks (suqour) counseled against joining the government but lost the internal debate. There was no point, in their view, to accept token ministries, to have enough power to be criticized but not enough to actually change anything.

The Brotherhood’s most prominent hawk, Mohamed Abu Faris, who I interviewed extensively for this book, published Participation in the Cabinet under Un-Islamic Regimes, in which he presents his case for abstaining from government. It makes for a fascinating read, especially today. He argues, for instance, that ministers in “un-Islamic” regimes have little choice but to bind themselves to constitutions that are based on un-Islamic sources of law.

After 1993, the issue has become even more contested, with hawks opposing any participation in the executive branch as long as the government maintains the peace treaty with Israel. For the Islamic Action Front, which proportionally has more Palestinian members than any other party, Israel is not just a foreign policy issue but a domestic one as well.

How have Islamists’ views evolved, both during the decades they were in the opposition and since the Arab uprisings?

At the organizational level, mainstream Islamists have mostly avoided delving into more foundational questions about the nature of the nation-state and how to reconcile it with non-Islamic sources of law. When they talk about politics, it is striking just how little theology figures into the discussion. For a movement ostensibly devoted to Islamization, Islamists had precious little to say in the lead-up to the Arab uprisings about the intellectual framework that would guide their approach to governing.

Which raises the question of how and why? Over the decades, Islamists had, in fact, changed. They didn’t become liberals – if they did, they’d no longer be Islamists. But there was a process of relative moderation, if we compare their positions on key issues, such as women’s and minority rights and political pluralism in one time period to a previous one. In effect, they diluted their Islamism in order to reach out to leftists and liberals (who offered a layer of protection against regime repression) and to appeal to the international community, something which became increasingly important after September 11, 2001, and particularly during George W. Bush’s “freedom agenda.”

Which raises the question of how and why? Over the decades, Islamists had, in fact, changed. They didn’t become liberals – if they did, they’d no longer be Islamists. But there was a process of relative moderation, if we compare their positions on key issues, such as women’s and minority rights and political pluralism in one time period to a previous one. In effect, they diluted their Islamism in order to reach out to leftists and liberals (who offered a layer of protection against regime repression) and to appeal to the international community, something which became increasingly important after September 11, 2001, and particularly during George W. Bush’s “freedom agenda.”

This dilution helped Islamists build cross-ideological coalitions against authoritarian regimes, but it only postponed – and obscured – fundamental questions about Islam and its relationship to the State, which would come to the fore after the democratic openings of the Arab spring. Even as the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt veered to the right, it preferred to speak in broad generalities about Islam and the Islamic state. They instinctively knew that details could be dangerous and would do little but frighten an array of domestic and international actors, who were all to ready to assume the worst about Islamist intentions.

The Brotherhood’s political party platform in 2007 was a telling example. It said that women could not hold the position of head of state (although they argued that this was simply an organizational position and did not reflect any desire to introduce a constitutional prohibition). It was not actually a new position and was the group’s longstanding policy, as expressed in its 1994 statement on “The Muslim Woman in Muslim Society and the Position toward Her Participation.” In the intervening years, however, they mostly stayed mum about it, which reflected a kind of strategic ambiguity. The lesson was learned, once again: When it comes to divisive issues such as women’s rights — to say nothing of more foundational issues such as the limits of popular sovereignty— it is easier to stick with generalities and to hide behind a kind of vague majoritarianism.

Photo credits: Jordan map by OCHA [CC-BY-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, Former President Mohamed Morsi via his official Facebook page

Related Program

The Islamists

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more