North Korea's American Allies

NKIDP e-Dossier no. 18

North Korea's American Allies:

DPRK Public Diplomacy and the American-Korean Friendship and Information Center, 1971-1976

By Brandon Gauthier

January 2015

Throughout the 1970s, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) waged an intensive diplomatic campaign to attract new supporters abroad and participate in the international community. From 1971-1978 alone, North Korea established ties with more than sixty new states; gained admission to the Non-Aligned Movement; and became a member of several United Nations organizations.[1] Pyongyang focused much of its diplomatic efforts on Africa in particular, presenting Kim Il Sung’s wise leadership as a model for the post-colonial world.[2]

Alongside these initiatives, Pyongyang launched public diplomacy campaigns in approximately fifty countries and funded some 200 “friendship” organizations abroad.[3] Through “people-to-people diplomacy,” North Korea hoped to improve its standing in the international community and foster support for its positions in the United Nations General Assembly.

North Korea sought to influence United States public opinion as part of that broader campaign over the first half of the 1970s. The DPRK published full-page advertisements in the American media[4], and Kim Il Sung offered exclusive interviews to Harrison Salisbury and Selig Harrison of the New York Times and Washington Post, respectively.[5] The DPRK’s nominal legislative body, the Supreme People’s Assembly, even sent two unprecedented letters to the United States Congress in 1973 and 1974.[6] In all of these initiatives, Pyongyang attempted to create public support for the removal of American troops from South Korea and portrayed itself as a victim of U.S. imperialism.

The documents presented here describe the efforts of the American-Korean Friendship and Information Center (AKFIC), an organization at the forefront of that public diplomacy effort.[7] In close cooperation with the North Korean government, members of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA), and a small number of professors, formed the AKFIC as an “anti-imperialist peace organization” that demanded the removal of U.S. troops from South Korea. Seeking to appeal to a burgeoning anti-war movement in the United States, the group argued that the continued presence of American forces in Korea would provoke a new conflict on the divided peninsula—a “second war in Asia nobody wants.”[8]

The AKFIC did not, however, simply parrot Pyongyang’s propaganda about the greatness of Kim Il Sung. To the contrary, the group reformulated North Korean arguments through the lens of the Vietnam War in an effort to gain support from the anti-war movement. The organization emerged as the result of both North Korean efforts to sway American public opinion and as a product of a radical far-left that conceived of U.S. foreign policy as a threat to “anti-imperialist” movements across the developing world. During the AKFIC’s brief existence from 1971-1976, the group gained few supporters in the United States. But its history remains significant, providing an example of North Korean collaboration with foreign publics in “private-public partnerships” throughout the 1970s.[9]

A logo for the American-Korean Friendship and Information Center, taken from an AKFIC publication, Korea Focus.

The founding of the AKFIC came after a delegation of the CPUSA, including Joseph Brandt, Henry and Fern Winston, and Victor and Ellen Perlo, visited North Korea at the invitation of DPRK officials in October 1970.[10] There, Henry Winston, Chairman of the National Committee of the CPUSA, expressed support for Kim Il Sung’s government on behalf of the American people. Upon the delegation’s return, Brandt—formerly the editor of the CPUSA’s Daily World—began reaching out to activists from diverse causes, hoping to build support for a new organization opposed to the presence of U.S. forces in Vietnam and Korea.[11]

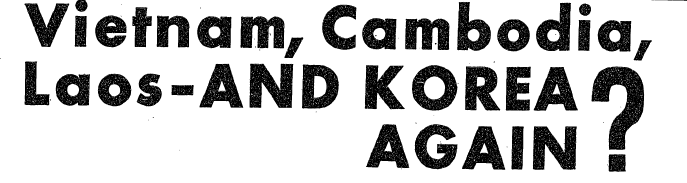

On February 24, 1971, Professor Howard Parsons of the University of Connecticut, Bridgeport, joined Brandt in announcing the creation of the American-Korean Friendship and Information Center from a newly rented Fifth Avenue office in New York City. As they held the organization’s first press conference, an advertisement appeared in the New York Times, announcing the creation of the AKFIC and warning of a new war in Korea if the U.S. did not remove its troops from the peninsula (Document No. 1). “Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos—AND KOREA AGAIN?” exclaimed the headline. If the removal of U.S. forces from South Vietnam would end the war in Southeast Asia, the group claimed, the removal of American GIs from South Korea would prevent a new one in East Asia. “BRING ALL THE TROOPS HOME NOW!” the advertisement declared.[12]

An advertisement, paid for by the American-Korean Friendship and Information Center, appeared in the New York Times to announce the founding of the AKFIC in February 1971 (Document No. 1)

Concurrently, the AKFIC published a position paper, “Operation War Shift” (Document No. 2), describing its objectives in the context of the Vietnam War. The paper asked readers: “Will the decade of the 1970s witness a new Vietnam in Korea?”[13] The White House, the organization argued, sought to destroy the DPRK and would allow a revitalized Japan to dominate Korea once again. The American public, the AKFIC implored, had to demand the withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Korea and insist that the White House end its support for Park Chung Hee’s regime in Seoul—the alternative, the position paper argued, was “a new holocaust” in Korea.[14]

AKFIC publications, seeking to appeal to the anti-war movement, reiterated these themes repeatedly. After the withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Vietnam in January 1973, the group urged the peace movement to focus its energies anew on Korea. The organization stated: “We believe that millions of American peace-loving people, who played a role in securing peace in Vietnam will continue to fight against the pressure of imperialist arms in all of Asia, especially Korea.”[15] Those who had struggled against “U.S. aggression” in Southeast Asia, the AKFIC argued, should “engage with us in the struggle to remove U.S. troops from Korea and leave Korea to the Korean people as Vietnam is now being left to the Vietnamese people.” From this perspective, U.S. policies in South Vietnam and South Korea were inseparable—one could not oppose American involvement in the former while remaining ambivalent about the latter.

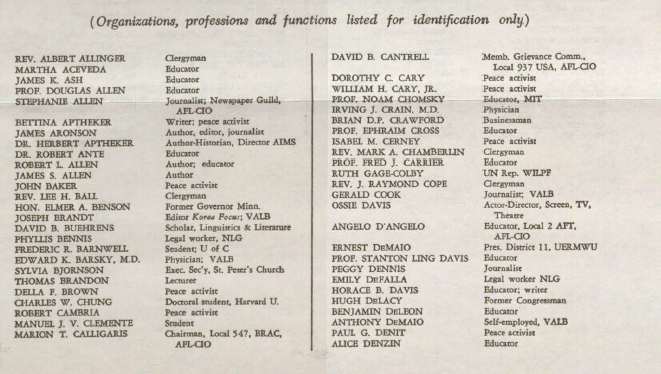

With this conviction, the AKFIC engaged in numerous activities to attract support from the American public. The group printed a periodic journal Korea Focus, hosted public forums and college lectures, and participated in anti-war rallies. The organization claimed to have the backing of 100 “organizing sponsors,” including professors, attorneys, artists, religious figures, and activists from numerous causes.[16] In reality, most of these supporters—from Howard Zinn to Jean Quan (an Asian-American activist who currently serves as the mayor of Oakland)[17]—did little else other than agree to have their names included on a list in exchange for North Korean literature.[18] Thus, the group never succeeded at attracting much support from the anti-war movement, much less the American public; a small number of passionate figures from the CPUSA and academia would remain the organization’s most active supporters.[19]

A list of "supporters" of the American-Korean Friendship and Information Center, published in an issue of Korea Focus in 1974 (Document No. 11)

The AKFIC disavowed any ties with North Korea or any other foreign state (Document No. 5). The group claimed to operate solely off of private donations, paying for its Manhattan office through fundraising efforts like “Operation Shoestring” in 1971.[20] (However, John Woodford, a former Vice Chairmen of the group, and Dae-Sook Suh, a prominent historian of Korean communism, both contend that Pyongyang funded the organization.[21]) In turn, the AKFIC made no secret of its loyalties. “We are partisan,” the group declared unabashedly, “we support 100 per cent…the people of the DPRK under a socialist system and we are 100 per cent behind the efforts of the DPRK to reunify the Korean nation.”[22] If North Korea’s American supporters disclaimed any association with Pyongyang, they made no effort to hide the fact that they worked energetically on its behalf in the United States.

Financial contributions aside, North Korea supported the AKFIC in numerous ways. Pyongyang, for instance, provided literature and movies for the group’s events and invited official delegations to visit the DPRK and report on their experiences in Korea Focus (Document No. 6 and Document No. 12). They even arranged for an AFKIC interview with Kim Il Sung (Document No. 4).[23] The North Korean leader himself praised the group’s efforts at giving “wide publicity to our people’s struggle [in the United States]…exposing the fascist dictatorship of South Korean reactionaries…as well as U.S. aggression in Korea.”[24]

North Korean leader Kim Il Sung answers questions posed by the American-Korean Friendship and Information Center in 1974 (Document No. 4).

In that regard, the AKFIC repeatedly sought to draw public attention to North Korean initiatives towards the United States. When North Korea’s Supreme People’s Assembly sent a letter to the U.S. Congress in April 1973—calling for the removal of U.S. forces from South Korea and an end to U.S. “interference in the internal affairs of the Korean people” (Document No. 8)—the AKFIC lobbied the legislative body on Pyongyang’s behalf, contacting every member of Congress. In doing so, the group expressed its displeasure that the American legislative body had refused to respond to the North Korean letter (Document No. 7). In the aftermath of a second overture from North Korea’s SPA in March 1974, the AKFIC mobilized a letter-writing campaign among its supporters (Document No. 10 and Document No. 11), urging Congressional representatives and senators to embrace the DPRK’s formula for peace and respond to Pyongyang. The ultimate refusal of Congress to do so was “shockingly discourteous,” from the AKFIC’s perspective—an “incomprehensible refusal to explore a welcome opportunity to create a meaningful state of peace in a most critical area of Asia.” Those complaints, however, did little else other than remind the House Committee on Internal Security about the existence of the AKFIC.[25]

As Pyongyang reduced funding for overseas “friendship” organizations in the latter half of the 1970s, the AKFIC faced financial problems and quietly disbanded in 1976.[26] The anti-war movement had little sympathy for its arguments equating U.S. policies in Korea and Vietnam. College students, as Bruce Cumings and Jon Halliday have noted, never ran “through the streets of Berkeley shouting, ‘Kim, Kim, Kim Il Sung.’”[27] The mysterious Cold War beginnings of the DPRK—as well as extraordinarily bitter memories of the Korean War and subsequent crises between the U.S. and North Korea—left few Americans sympathetic to North Korean appeals to “leave Korea to the Koreans.”[28] To most, Kim Il Sung’s regime remained the “ugliest of the communist uglies,” as Life magazine put it in 1972.[29]

The documents provided here offer a rare window into the thinking of North Korea’s American sympathizers in the twilight and aftermath of the Vietnam War. Representing an all but forgotten moment of cooperation between Pyongyang and a disaffected radical far-left in the CPUSA and academia, they demonstrate how the AKFIC conceptualized a uniquely North Korean vision of Korea’s past, present, and future (See Document No. 2 and Document No. 13, in particular). More broadly, these documents are emblematic of the innovative ways that North Korea sought to foster change at home through “people’s diplomacy” abroad in an era of globalization that proved seductive even for the so-called “Hermit Kingdom.”

Brandon K. Gauthier graduated from Elon University in 2006 with a B.A. in political science and completed his M.A. in history at Fordham University in 2010. He is presently a Ph.D. candidate in American history at Fordham University. Specializing in U.S. foreign relations, his dissertation examines the history of U.S.-DPRK relations from 1948 to 1996. Gauthier’s research specifically historicizes competing cultural and political visions of North Korea in American society and explains the process through which integrated links between culture, identity, and foreign policy shaped U.S.-DPRK diplomatic history. He has previously written for the Atlantic.com, Yonsei Journal of International Studies, The Oral History Review, Shreveport Times, and NKnews.org.

Document List

Document No. 1

“Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos—and Korea Again?”

[Source: New York Times, February 25, 1971, p. 41.]

Document No. 2

American-Korean Friendship and Information Center, “Operation War Shift: Position Paper, Second (Revised) Edition,” 1971

[Source: Central Connecticut State University Library, 951.9 O546. Obtained by Brandon Gauthier.]

Document No. 3

Insert included in “Operation War Shift: Position Paper, Second (Revised) Edition,” 1971

[Source: Central Connecticut State University Library, 951.9 O546. Obtained by Brandon Gauthier.]

Document No. 4

Kim Il Sung, Korea Must Be Reunified: A Call for Friendship between the Peoples of the United States and the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea (New York: American-Korean Friendship and Information Center, 1974)

[Source: Mississippi State University Mitchell Memorial Library, DS917 .K56 1972. Obtained by Brandon Gauthier.]

Document No. 5

“[About the] AFKIC: American-Korean Friendship and Information Center,” 1972

[Source: Korea Focus 1, no. 2 (Spring 1972): 62-64. Obtained by Brandon Gauthier.]

Document No. 6

“A Visit to the DPRK: A Report from the Delegation of the American-Korean Friendship and Information Center to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” 1972

[Source: Korea Focus 1, no. 2 (Spring 1972): 23-29. Obtained by Brandon Gauthier.]

Document No. 7

“For Congress to Act We Must Speak Out, Loud and Clear!,” 1973

[Source: Korea Focus 2, no. 2 (Spring 1973): 27, 30. Obtained by Brandon Gauthier.]

Document No. 8

“Letter to the Congress of the United States from the Supreme People’s Assembly, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea,” 6 April 1973

[Source: Korea Focus 2, no. 2 (Spring 1973): 28-29. Obtained by Brandon Gauthier.]

Document No. 9

“Comments from Leading American Senators,” 1973

[Source: Korea Focus 2, no. 2 (Spring 1973): 28-29. Obtained by Brandon Gauthier.]

Document No. 10

Letter from George B. Murphy, Jr., Fred J. Carrier, and Joseph Brandt, 1974

[Source: Enclosed in Korea Focus 3, no. 1 (August-September 1974). Obtained by Brandon Gauthier.]

Document No. 11

“A Letter to Congress: Appeal of Constituents and Voters to Our Elected Representatives in the Congress of the USA,” 6 April 1973

[Source: Enclosed in Korea Focus 3, no. 1 (August-September 1974). Obtained by Brandon Gauthier.]

Document No. 12

Fred Carrier, “North Korean Journey: A View of Workers’ Democracy,” 1974

[Source: Enclosed in Korea Focus 2, no. 3 (January-February 1974). Obtained by Brandon Gauthier.]

Document No. 13

Korea: Uneasy Truce in the Land of the Morning Calm (New York: American-Korean Friendship and Information Center, 1976)

n[Source: Frostburg State University, Archives Pamphlet, 1112. Obtained by Brandon Gauthier.]

[1] See Charles K. Armstrong Tyranny of the Weak: North Korea and the World, 1950-1992 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2013), 168, 178-179; Dae-Sook Suh, Kim Il Sung: The North Korean Leader (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), 262; Byung-Chul Koh, The Foreign Policy Systems of North and South Korea (Berkley, CA: University of California Press, 1984), 11-12.

[2] See Charles Armstrong’s discussion of “Juche in Africa,” Tyranny of the Weak, 192-197.

[3] Dae-Sook Suh, Kim Il Sung: The North Korean Leader, 267. Public diplomacy, as Nicholas Cull has noted, consists of “listening” (ascertaining and examining the feelings of a foreign public); “advocacy” (directly advocating a policy position to a foreign populace); “cultural diplomacy” (using cultural contacts to influence a foreign public’s perceptions of the initiating country); “exchange diplomacy” (engaging in reciprocal exchanges); and “international bro adcasting” (using state funds to disseminate news to a foreign public). See Nicholas J. Cull, The Cold War and the United States Information Agency: American Propaganda and Public Diplomacy, 1945-1989 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), xiv-xvi.

[4] For a discussion of North Korean advertisements in the Western media from 1969 to 1997, see Benjamin R. Young, “How North Koreans ads in western newspapers backfired,” NKnews.org, September 27, 2013 http://www.nknews.org/2013/09/how-north-koreans-ads-in-western-newspapers-backfired/.

[5] See “Excerpts from Interview with North Korea Premier on Policy towards US,” New York Times, May 31, 1972; Selig S. Harrison, “Kim Seeks Summit, Korean Troop Cuts,” Washington Post, June 26, 1972. For Harrison Salisbury’s personal notes on this trip, see, Columbia University Rare Books & Manuscript Library, Harrison Salisbury Papers 1927-1999, Box 329, Folder 2: “Travel: North Korea Trip.”

[6] Andrew Nahm, “The United States and North Korea since 1945,” in Korean-American Relations, 1866-1997, eds. Yur-Bok Lee and Wayne Patterson (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1999), 113.

[7] This introduction is based on a prior essay on the AKFIC by the author. See Brandon K. Gauthier, “The American-Korean Friendship and Information Center and North Korean Public Diplomacy, 1971-1976,” Yonsei Journal of International Studies 6, no. 1 (Spring/Summer 2014): 151-162. The AKFIC is briefly mentioned in Dae-Sook Suh, Kim Il Sung: The North Korean Leader, 392n41; Nahm, “The United States and North Korea since 1945,” in Korean-American Relations, 1866-1997,, 112.

[8]“Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos – AND KOREA AGAIN,” New York Times, Feb. 25, 1971, 41.

[9] North Korea, as Charles Armstrong states, pursued a “peculiar and limited kind of globalization…avant la lettre” in the 1970s that was a precursor to South Korea’s segyewha policy some twenty years later. See Armstrong, Tyranny of the Weak, 168. On “private-public partnerships,” see: Kenneth Osgood, ed., The United States and Public Diplomacy: New Directions in Cultural and International History (Boston, MA: Brill, 2010), 8-9n17.

[10] See: Richard H. Ichord, “Advertisers and Agitators,” Washington Report, April 12, 1970, WR 71-7. Ellen Perlo later discussed parts of this trip in an article for the AKFIC’s journal. See Ellen Perlo, “Happy Children: Asia's Future is in Their Hands,” Korea Focus 1, no. 2 (Spring 1972): 37-38.

[11] For more information on Joseph Brandt, including his correspondence, reports, and speeches from the 1960s to the 1990s, see NYU Tamiment Library, Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, CPUSA Records, TAM.132, Series IX, Subseries A, Box 152, Folder 13.

[12] Emphasis added.

[13] Emphasis added. AKFIC, “Operation War Shift: Position Paper,” Second Revised Edition, 1971, 3.

[14] AKFIC, “Operation War Shift: Position Paper,” Second Revised Edition, 1971, 3

[15] “Korea Focus Executive Board” Korea Focus 2, no. 1 (Jan.-Feb. 1971): 1.

[16] For the lists of organizing sponsors, see Document No. 1 and Document No. 3.

[17] Mayor Quan’s office did not respond to the author’s request for an interview about her participation in the AKFIC. The AKFIC also included Nan Orrock—currently a State Senator in Georgia—on its list of organizing sponsors under the name of Nan Guerrero. State Senator Orrock’s office would not discuss her participation in the group with the author.

[18] Robert S. Cohen, telephone interview by the author, December 10, 2013.

[19] Former Communist Party Vice Presidential Candidate Jarvis Tyner recalls that Joseph Brandt enthusiastically promoted the AKFIC at CPUSA meetings and ensured that Communist Party bookstores carried North Korean literature. Jarvis Tyner telephone interview by the author, March 4, 2014. Officials at Villanova University nearly fired Professor Fred Carrier, a leading figure in the AKFIC, from the History Department for his outspoken support for North Korea; Dr. James Bergquist, Professor Emeritus of History at Villanova University, personal communication with the author, April 11, 2014. Carrier authored a book on his own experiences in North Korea on behalf of the AKFIC entitled: North Korean Journey: The Revolution against Colonialism (New York: International Publishers, 1975).

[20] “Operation Shoe String,” Korea Focus 1, no. 1 (Fall 1971): 63.

[21] Dr. Suh, who never joined, remembers teasing AKFIC members over their financial ties as they screened a North Korean film at the University of Hawaii. “Please don’t do a half-ass job,” he told them, “North Korea does not have that much money.” Dae-Sook Suh, telephone interview by the author, February 25, 2014. John Woodford, former editor-in-chief of Muhammad Speaks, explained that he was quite surprised when Joe Walker—a friend and fellow Vice Chairman of the AKFIC—somehow acquired the funds to travel to the DPRK with Joseph Brandt and Howard Parsons in August 1971. John Woodford, telephone interview by the author, February 25, 2014.

[22]“[About the] AKFIC: American-Korean Friendship and Information Center,” Korea Focus 1, no. 2 (Spring 1972): 63.

[23] Prof. Howard Parsons described the AKFIC’s first trip to the DPRK in Korea Focus (Document No. 5), and in “Socialism in the Land Of the Fresh Morning: A Journey to Korea,” New World Review 40, no. 1 (April 1972): 67-76.

[24]AKFIC Pamphlet, “KOREA MUST BE REUNIFIED: A Call for Friendship between the Peoples of the United States and the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea by KIM IL SUNG: An Exclusive Interview with the President of the DPRK” (New York, 1974), 5.

[25] During internal security hearings, the House Committee denounced the AKFIC in the congressional record as a front organization for the CPUSA. See: Hearings Before the Select Committee on Committees: House of Representatives, Ninety-Third Congress, Vol. 1 of 3, Part 2 of 2 (Washington, D.C.: US GPO, 1973), 485-486.

[26] None of the DPRK’s “friendship” organizations, Dae-Sook Suh notes, survived without North Korean funding, see: Kim Il Sung: The North Korean Leader, 267. The CPUSA would, however, maintain contacts with the DPRK. At one point, Kim Il Sung sent CPUSA General Secretary Gus Hall a large box of presents, including: “1. Flower Bottle Embroidered with Silver Thread 2. Tea Set 3. Bed Cover 4. Embroidery of Scenery 5. Red Insam [Ginseng],” see: NYU Tamiment Library, Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, CPUSA Records, TAM.132, Series IX, Subseries A, Box 196, Folder 10.

[27] Bruce Cumings and Jon Halliday, Korea: the Unknown War (New York: Pantheon, 1988), 204. Quoted in Bradley K. Martin, Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2006), 134.

[28] Charles K. Armstrong has noted that “the history of the DPRK was too ambiguous—neither a Soviet ‘satellite nor a clear-cut case of indigenous revolution—to appeal to the far-left vanguard of the West.” See Armstrong, Tyranny of the Weak, 177.

[29] “Editorials,” Life, August 4, 1972, 34.s

About the Author

Brandon Gauthier

Read More

North Korea International Documentation Project

The North Korea International Documentation Project serves as an informational clearinghouse on North Korea for the scholarly and policymaking communities, disseminating documents on the DPRK from its former communist allies that provide valuable insight into the actions and nature of the North Korean state. It is part of the Wilson Center's History and Public Policy Program. Read more

Cold War International History Project

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Through an award winning Digital Archive, the Project allows scholars, journalists, students, and the interested public to reassess the Cold War and its many contemporary legacies. It is part of the Wilson Center's History and Public Policy Program. Read more

History and Public Policy Program

The History and Public Policy Program makes public the primary source record of 20th and 21st century international history from repositories around the world, facilitates scholarship based on those records, and uses these materials to provide context for classroom, public, and policy debates on global affairs. Read more