The Algerian Revolution and the Communist Bloc

CWIHP e-Dossier No. 62

The Algerian Revolution and the Communist Bloc: Evidence from the Algerian National Archives

by Pierre Asselin, Professor of History, Hawaii Pacific University

February 2015

The onset of the Algerian War of Independence in November 1954 was an important development in the international history of the Cold War. Coming as it did on the heels of the end of the First Indochinese War, the Algerian conflict further emboldened national liberation forces throughout the colonial and semi-colonial world, a region of increasing importance to policymakers in Washington and Moscow. For Soviet and other communists committed to world revolution and proletarian internationalism in particular, the so-called Third World offered infinite possibilities, a fertile ground for the pursuit and realization of their aspirations, including the neutralization of American and other western imperialistic ambitions.

Entering the Algerian National Archives (Archives nationales d’Algérie). Photo: P. Asselin.

The leaders of the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN, Front de libération nationale), the umbrella organization that coordinated the struggle against France, were nationalists, first and foremost, who believed in the merits of revolutionary violence to secure the independence of their country (applied through the movement’s armed wing, the National Liberation Army [ALN, Armée de libération nationale]). While they may have harbored leftist proclivities at one point or another, those leaders never considered themselves—or pretended to be—communists or dedicated socialists. In fact, according to one document (Document No. 3.1), members of the Algerian Communist Party (PCA, Parti communiste algérien) were in their eyes “counter-revolutionaries” working “outside” the revolution. Theirs was a movement seeking the abolition of French colonial control, and its substitution with sovereign Algerian rule under a secular nationalist regime.

However, such proclivities did not mean that FLN leaders altogether refused to engage the socialist camp and collaborate with it. Despite their lack of adherence to communist ideals and manifest contempt for Algeria’s own communist party, they recognized the congruence of certain interests between themselves and the communist camp, and the potential for using that camp to meet their ends by soliciting its assistance.

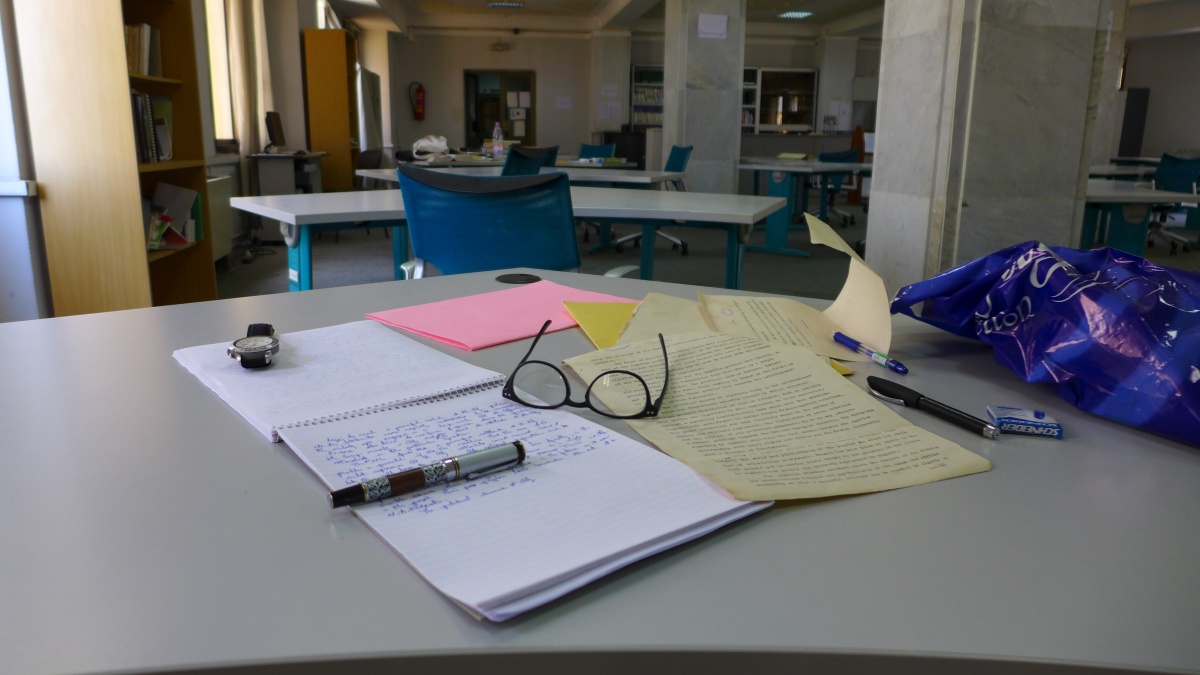

Inside the reading room at the Algerian National Archives. Photo: P. Asselin.

In September 1958, the FLN founded the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA, Gouvernement provisoire de la République algérienne) under the presidency of Ferhat Abbas, a moderate nationalist.[1] The GPRA effectively replaced the Coordination and Implementation Committee (CCE, Comité de Coordination et d’Exécution), the core decision-making organ within the FLN. Based first in Cairo (1958-60) and then Tunis (1960-62), the GPRA not only directed the Algerian revolutionary effort, but also served the purposes of legitimizing the Algerian independence struggle internationally while acting as a potent diplomatic tool for enlisting foreign support for that struggle. The GPRA eventually secured recognition from a variety of states (Document No. 13), which in turn allowed it to open in those states diplomatic missions whose primary tasks consisted of publicizing the plight of the Algerian people while soliciting material and other forms of assistance from host and other governments. Among the states that promptly recognized the GPRA were members of the socialist camp, which would thereafter play an increasingly meaningful role in the Algerian conflict. Indeed, it was not long after its establishment that the GPRA engaged communist bloc countries with a view to garnering moral, political, and material support from it. To that latter end it dispatched missions to communist states, or otherwise entertained relations with them through their diplomats posted in Egypt and Tunisia.

Evidence from the Algerian National Archives (ANA, Archives nationales d’Algérie) sheds revealing light on the relations entertained by the GPRA with the socialist camp. While that record is partial at best, it nonetheless provides us with interesting insights into the way Algerian revolutionary leaders perceived the communist bloc and sought to curry favor from it (Document No. 1.1 and Document No. 14). It also gives us a sense of the type of support proffered by members of that bloc (Document No. 2, Document No. 3.2, Document No. 7, and Document No. 15), as well as of the means by which material assistance reached the ALN in Algeria proper (Document No. 4).

One document addresses the GPRA’s efforts to “internationalize” the Algerian struggle by using the United Nations (Document No. 10), a story related in Matthew Connelly’s A Diplomatic Revolution, and another its attempt to pressure the Afro-Asian bloc into doing more on behalf of Algeria (Document No. 11).[2] To be sure, despite their limited resources, Algerian revolutionary leaders closely monitored the so-called international situation, and actually sought to tailor their foreign policy accordingly (Document No. 8, Document No. 12, and Document No. 14). Among the most remarkable documents in this collection are a summary of a meeting that took place in Havana in 1961 between two GPRA envoys and Fidel Castro and Che Guevara (Document No. 5), and the minutes of a meeting during which the Chinese ambassador in Cairo lectured GPRA envoys on the merits of fighting while negotiating (Document No. 6).

***

My visit to the Algerian National Archives —my first and only, to this point—took place in June of 2014, and lasted two weeks. Due to a recent reshuffling of personnel, including the appointment of a new director, access to materials proved more challenging than I—as well as two American graduate students who arrived shortly after I did—had anticipated. Like most American scholars seeking to conduct research in Algeria, prior to my visit I sought “sponsorship” from a local organization —the Centre d’études maghrébines en Algérie (CEMA) in Oran, in this instance—which provided me with a letter of invitation (to secure a visa) and petitioned the ANA on my behalf for access to its collection.[1]

Working with GPRA documents at the Algerian National Archives. Photo: P. Asselin.

I had been told that CEMA sponsorship effectively guaranteed access to the archives; it turned out that was no longer the case. For reasons never made clear to me, the ANA’s new director would not honor CEMA’s petition on my behalf, which I only found out after my arrival in Algiers. Under the new leadership, an assistant to the Director told me (as the latter was away on “mission”), researchers must petition the National Archives directly to gain access to its collection. After lengthy discussions with the Assistant, during which I explained my purposes and specified that I am actually a Vietnam scholar seeking documentation on relations between Algeria and Vietnam/the Communist camp during the Cold War, I was given permission to request and eventually read files from the GPRA record group, but reminded that next time I would need to petition the ANA directly.[2] In retrospect, that experience was in many ways reminiscent of my first attempts to access the collection of National Archives Center 3 in Hanoi, nearly two decades ago. As has proven true of my dealings with the Vietnamese, so it might be with the Algerians that the more familiar they become with one’s person and work, the easier they make it to access their archives. Scholars such as Jeffrey Byrne of the University of British Columbia would know more about this and related matters; after all, Byrne is a bona fide Algeria specialist who has repeatedly visited that country for research. His advice to me actually proved invaluable on making my trip as productive as it was.

The ANA main building is located at 20 Rue Hassan Bennamane in Birkhadem, Algiers, and is easily accessible by public transportation from the city center. The reading room is on-site, and consists of 26 large tables and very comfortable office-type chairs; the members of its staff proved incredibly helpful and friendly, and speak impeccable French. For students of the Cold War, the <GPRA, 1958-62> record group (fond) is arguably the most interesting and easily accessible. Practically all files in that collection are in French, which, ironically enough, remained the lingua franca of Algerian revolutionary authorities throughout the war. Access to other pertinent record groups is likely to require an extended stay in Algiers, and a great deal of patience. Post-independence (1962) diplomatic materials are for all intents and purposes off-limits. To my knowledge, only one western scholar—the aforementioned Byrne—has been granted permission to peruse such records. I was told by the ANA staff during my visit that to see Foreign Ministry files of the post-independence era, I would have to present a formal request to that end to the Algerian Foreign Ministry through its embassy in Washington, D.C., or its mission in New York. I have yet to do so.

I extend my utmost gratitude to the Cold War International History Project and its director, Christian Ostermann, for a generous grant that helped make possible this research trip to Algeria. Profuse thanks, too, to my student, Paulina Kostrzewski, for her assistance in transcribing all the documents that appear in this collection and, above all, for her patience and diligence.

Pierre Asselin is professor of history at Hawaii Pacific University in Honolulu. He is the author of A Bitter Peace: Washington, Hanoi, and the Making of the Paris Agreement (University of North Carolina Press, 2002) and Hanoi’s Road to the Vietnam War, 1954-1965 (University of California Press, 2013). Other recent and notable publications include “The Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the 1954 Geneva Conference: A Revisionist Critique” in Cold War History (2011); “Revisionism Triumphant: Hanoi’s Diplomatic Strategy in the Nixon Era” in Journal of Cold War Studies (2011); and “‘We Don’t Want a Munich’: Hanoi’s Diplomatic Strategy, 1965-1968” in Diplomatic History (2012). His work has featured prominently in France and as well as in Vietnam. He is co-editor of The Cambridge History of the Vietnam War, Volume III: Endings (Cambridge University Press, forthcoming [2018]), and working on the completion of Vietnam’s American War: A History with Documents (Cambridge University Press, forthcoming [2016]), which surveys the Vietnamese communist experience during the Vietnam War. He is also developing a third monograph exploring the origins and conduct of Hanoi’s so-called diplomatic struggle during the Vietnam War on the basis of archival evidence from Vietnam, Algeria, and elsewhere.

List of Documents

Document No. 1.1

Development of Relations with Socialist Countries since March 19, 1961

[Source: Dossier 08/13/07 : Rapport sur le GPRA et ses possibilités politiques dans les pays de l’Est à l’exception de la Yougoslavie [Report on GPRA Political Possibilities in Eastern bloc Countries, with the Exception of Yugoslavia] (sans date); Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document 1.2

Annex #1 to 'Development of Relations with Socialist Countries since March 19, 1961'

[Source: Dossier 08/13/07 : Rapport sur le GPRA et ses possibilités politiques dans les pays de l’Est à l’exception de la Yougoslavie [Report on GPRA Political Possibilities in Eastern bloc Countries, with the Exception of Yugoslavia] (sans date); Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document 1.3

Annex #2 to 'Development of Relations with Socialist Countries since March 19, 1961'

[Source: Dossier 08/13/07 : Rapport sur le GPRA et ses possibilités politiques dans les pays de l’Est à l’exception de la Yougoslavie [Report on GPRA Political Possibilities in Eastern bloc Countries, with the Exception of Yugoslavia] (sans date); Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document 1.4

Report attached to 'Development of Relations with Socialist Countries since March 19, 1961'

[Source: Dossier 08/13/07 : Rapport sur le GPRA et ses possibilités politiques dans les pays de l’Est à l’exception de la Yougoslavie [Report on GPRA Political Possibilities in Eastern bloc Countries, with the Exception of Yugoslavia] (sans date); Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 2

Letter from the GPRA Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the GPRA Ministry of the Interior, ‘Material Assistance,’ 10 February 1962

[Source: Dossier 55/03/01 : [untitled] ; Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 3.1

Summary of Meeting between Third Secretary Hassenkhe and Head of Socialist Countries Bureau Yaker, 16 May 1961

[Source: Dossier 47/04/01 : Compte-rendu d’entretien entre la section des pays socialistes et les représentants de la République Démocratique d’Allemagne [Summary of Meetings between the Bureau for Socialist Countries and the Representatives of the German Democratic Republic] (16-17 Mai 1961); Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 3.2

Summary of Meeting between Ambassador to Arab States Kiesewetter and General Secretary Belhocine and Head of Bureau Waker, 17 June 1961

[Source: Dossier 47/04/01 : Compte-rendu d’entretien entre la section des pays socialistes et les représentants de la République Démocratique d’Allemagne [Summary of Meetings between the Bureau for Socialist Countries and the Representatives of the German Democratic Republic] (16-17 Mai 1961); Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 3.3

Appendix to 'Summary of Meeting between Ambassador to Arab States Kiesewetter and General Secretary Belhocine and Head of Bureau Waker,’ 18 June 1961

[Source: Dossier 47/04/01 : Compte-rendu d’entretien entre la section des pays socialistes et les représentants de la République Démocratique d’Allemagne [Summary of Meetings between the Bureau for Socialist Countries and the Representatives of the German Democratic Republic] (16-17 Mai 1961); Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 3.4

Annex #1 to 'Summary of Meeting between Ambassador to Arab States Kiesewetter and General Secretary Belhocine and Head of Bureau Waker'

[Source: Dossier 47/04/01 : Compte-rendu d’entretien entre la section des pays socialistes et les représentants de la République Démocratique d’Allemagne [Summary of Meetings between the Bureau for Socialist Countries and the Representatives of the German Democratic Republic] (16-17 Mai 1961); Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 4

A. Bouzid, ‘Summary of Armament during the 1954 Revolution,’ July 1996

[Reference Collection of the Algerian National Archives. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 5

Note to the GPRA Minister of Foreign Affairs, ‘Mission to Cuba,’ 18 January 1962

[Source: Dossier 10/03/22 : Compte-rendu de mission de M. Lakhdar Brahimi à Cuba destinée au Ministre des affaires étrangères [Summary of the Mission of Mister Lakhdar Brahim to Cuba for the Minister of Foreign Affairs] (18 Janvier 1962); Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 6

Notes of Meeting between Boussouf, Benaouda, and Belhocine and the Chinese Ambassador, 20 April 1961

[Source: Dossier 18/05/25 : Procès-verbal analytique d’entretien du 20 et 21/4/1961 entre les Algériens (Boussouf, Benouda, Belhocine) et les Chinois (Ambassadeur et un secrétaire interprète) [Analytical Minutes of the Meeting of 20 to 21 April 1961 between the Algerians (Boussouf, Benouda, Belhocine) and the Chinese (Ambassador and Interpreter Secretary)] (sans date); Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 7

Letter to the GPRA Prime Minister, ‘Mission Summary,’ 1 September 1960

[Source: Dossier 11/01/13 : Compte-rendu de la réunion de la mission du Ministre de l’armement et des liaisons générales en date du 24 Aout 1960 au Caire auprès des ambassadeurs de Chine populaire et d’URSS destinée au Président du Conseil [Summary of the Mission of the Minister of Armaments and of General Communications of 24 August 1960 in Cairo to the Ambassadors of the People’s Republic of China and the USSR for the Prime Minister] (1 Septembre 1960) ; Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 8

Report from the General Secretary, ‘Our Diplomatic Action,’ 8 November 1960

[Source: Dossier 55/02/05 : Note au Vice-Président du Conseil, Ministre des affaires étrangères [Note to the Vice President of the Council, Minister of Foreign Affairs] (8 Novembre 1960) ; Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 9

The Algerian Problem, 1962

[Source: Dossier 37/01/11: Le problème algérien : comparaison avec la lutte chinoise [The Algerian Problem: Comparison with the Chinese Struggle] (1962) ; Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 10

The Internationalization of the Algerian Problem and Its Inscription on the Agenda of the General Assembly of the United Nations from 1957-1959

[Source: Dossier 37/01/10 : Internationalisation de la question algérienne et son inscription dans l’ordre du jour des travaux de l’assemblée générale des Nations Unies de 1957-1959 [The Internationalization of the Algerian Problem and Its Inscription on the Agenda of the General Assembly of the United Nations from 1957-1959] (1957-59); Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 11

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the GPRA, ‘Declaration of the Algerian Delegation at the Council of the Organization for Afro-Asian Solidarity,’ 23 January 1961

[Source: Dossier 43/02/07: Déclaration de la délégation algérienne au conseil de l’organisation de la solidarité Afro-asiatique [Declaration of the Algerian Delegation at the Council of the Organization for Afro-Asian Solidarity] (24 Janvier 1961) ; Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 12

Letter from the GPRA Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ‘Confidential Note to the Heads of Missions and Delegations,’ 31January 1962

[Source: Dossier 40/04/32: Note confidentielle de la direction centrale du Ministère des affaires étrangères aux chefs de missions et délégations à l’extérieur portant sur la position du FLN vis-à-vis des questions internationales débattues et ses positions [Confidential Note from the Central Direction of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the Heads of Missions and Delegations Abroad, on the Positions of the FLN on Major International Issues] (1962) ; Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 13

List of Recognitions of the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA)

[Source: Dossier 33/02 : Tableau des reconnaissances des pays pour le Gouvernement Provisoire de la République Algérienne (GPRA) [List of States Recognizing the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic] (sans date) ; Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 14

Note from the GPRA Secretary General to Foreign Missions and Delegations, ‘Our Foreign Policy,’ 4 October 1960

[Source: Dossier 41/05/14 : Note de Mabrouk Belhocine, secrétaire général par intérim du Ministère des affaires étrangères, aux missions et délégations à l’extérieur portant sur la politique extérieure du GPRA [Note from Mabrouk Belhocine, Interim Secretary General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, for Missions and Delegations Abroad, on the Foreign Policy of the GPRA] (4 Octobre 1960); Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

Document No. 15

Note from the GPRA General Secretary, ‘Issue: War Material,’ November 1960

[Source: Dossier 18/01/03 : Compte-rendu de l’entretien M. Krim Belkacem et M. Lin Cha Na, Premier conseiller, Ambassade de Chine [Summary of the Meeting between M. Krim Belkace and M. Lin Cha Na, First Adviser, Chinese Embassy] (1 Octobre 1960); Fond: GPRA, 1958-62; Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Alger. Translated from French and transcribed by Pierre Asselin, with Paulina Kostrzewski.]

[1] The CEMA is a private and independent research center under the American Institute for Maghrebian Studies (AIMS, Institut américain d’études maghrébines). Its mission consists in facilitating scholarship focusing on North Africa.

[2] I am not certain if these procedures remain in effect. Anyone interested in mining these archives should contact the ANA directly and, at a minimum, seek the advice of the very helpful staff at CEMA and of its director, Robert Parks (parks[at]cema-northafrica.org). Robert and his assistant, Karim Ouaras (ouaras[at]cema-northafrica.org), were instrumental in making my research trip possible, and I will be eternally grateful for all the help they rendered.

[1] Benyoucef Benkhedda succeeded Abbas as president in 1961. Other prominent members of the GPRA included Krim Belkacem (Vice President [1958-62], Minister of the Armed Forces [1958-60], Minister of Foreign Affairs [1960-61], Minister of the Interior [1961-62]); Ahmed Ben Bella (Vice President, in detention); Abdelhafid Boussouf (Minister of Armaments and of General Relations [1960-62]); and Hocine Ait Ahmed (Minister of State, in detention)

[2] Matthew Connelly, A Diplomatic Revolution: Algeria’s Fight for Independence and the Origins of the Post-Cold War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003).

About the Author

Pierre Asselin

Pierre Asselin is the Dwight E. Stanford Chair in the History of US Foreign Relations at San Diego State University. He is the author of A Bitter Peace: Washington, Hanoi, and the Making of the Paris Agreement (University of North Carolina Press, 2002), which won the 2003 Kenneth W. Baldridge Prize, and Hanoi’s Road to the Vietnam War, 1954-1965 (University of California Press, 2013), winner of the 2013 Arthur Goodzeit Book Award.

Read More

Cold War International History Project

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Through an award winning Digital Archive, the Project allows scholars, journalists, students, and the interested public to reassess the Cold War and its many contemporary legacies. It is part of the Wilson Center's History and Public Policy Program. Read more

History and Public Policy Program

The History and Public Policy Program makes public the primary source record of 20th and 21st century international history from repositories around the world, facilitates scholarship based on those records, and uses these materials to provide context for classroom, public, and policy debates on global affairs. Read more