Long before Auschwitz, long before Treblinka and Sobibor, there was Babi Yar—the sprawling ravine on the outskirts of Kyiv where the Nazis, with support from the locals, murdered 33,771 Jews in a two-day killing spree on September 29 and 30, 1941. The Holocaust as the “final solution” began here, in Ukraine and other Soviet territories. Over the fall of 1941 the number of victims at Babi Yar grew to 100,000, to include, beside the Jews, the mentally ill, Roma, Ukrainian nationalists, Communists, and other undesirables.

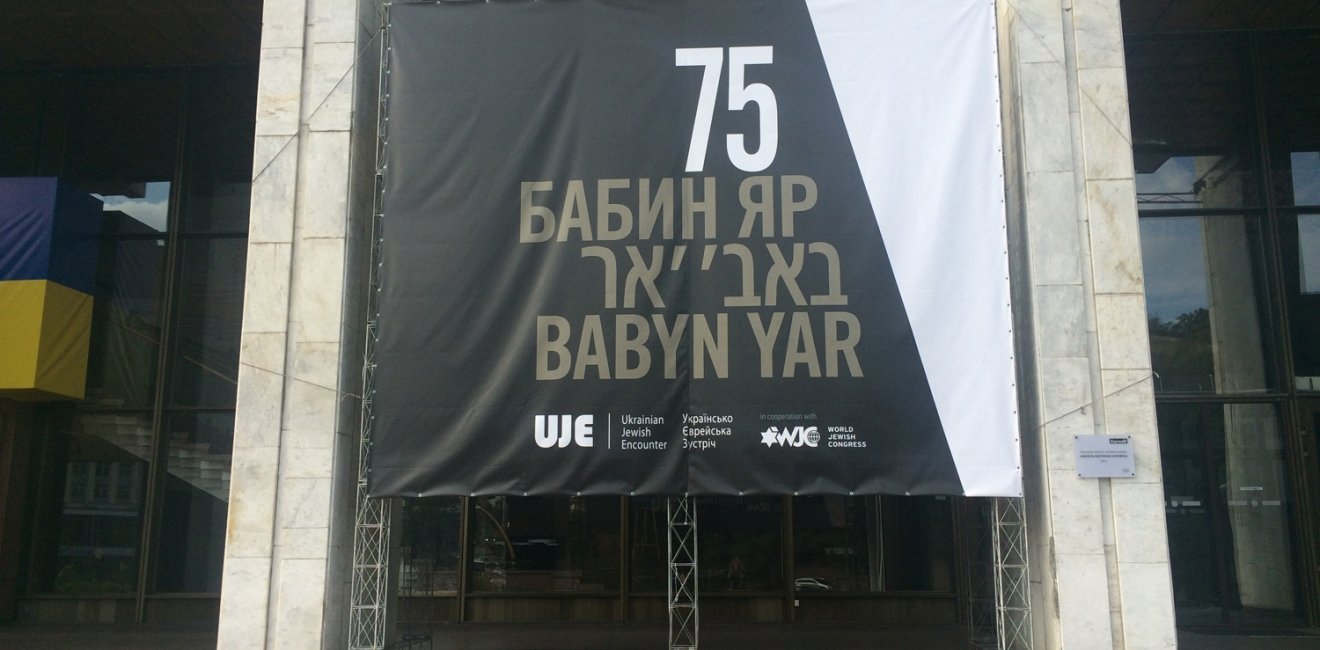

This week, as Kyiv commemorates the 75th anniversary of the tragedy, the city is home to much commemorative activity. Penny Pritzker, the U.S. secretary of commerce, who is said to have a personal connection to Babi Yar, is expected to arrive for the official ceremony. Israel’s president, Reuven Rivlin addressed a special parliamentary hearing on Babi Yar earlier in the week. Numerous American Jewish organizations are descending on Kyiv. A Canadian organization, Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), has put together a symposium, with participation from the celebrated historian Timothy Snyder. And the German Federal Agency for Civic Education will be holding its own symposium, “Mapping Memories.”

The buzz is understandable and appropriate. Seventy-five years after the event, Babi Yar, more than a site of the murder of innocents, stands as a symbol. First and foremost, it is a symbol of the other Holocaust—the “Holocaust by bullets” that unfolded behind the Iron Curtain and that remains poorly understood, even though 2.7 million, or half of all the Holocaust’s victims, perished here. “Every big city in Ukraine has its own Babi Yar,” said Dr. Egor Vradiy at the UJE’s symposium here in Kyiv. Boris Maftsir, a former researcher from Yad Vashem who made a documentary about the Holocaust in Belarus and is now making one about Babi Yar, estimates that there are as many as 400 sites of Jewish mass murders in Ukraine from the Word War II era.

Babi Yar is also a symbol of denial, desecration, and forgetting. Soviet historiography denied the specifically Jewish nature of the Nazi murders, referring to the murdered as “peaceful Soviet citizens.” The horrific ways in which the site and the bodies were treated in the following decades rival in horror the original murders. Eventually, what was once a series of ravines, some nearly 14.5 meters (45 feet) deep, became a virtually flat surface where locals walk their dogs and get together for a beer. The very landscape of Babi Yar seems to have been erased, along with the lives that were destroyed here.

Whereas in most of Europe and the United States, the Holocaust and its specific events are a horrific yet hardly controversial subject, in Ukraine a discussion of Babi Yar and of the Holocaust in general can become maddeningly complicated. Reactions can run the gamut from indifference, to repeating Soviet-era views that discount the specifically Jewish nature of the Holocaust, to resurrecting Nazi propaganda canards equating all Soviet Jews with communists and coming dangerously close to justifying the murders, to confessing to a general ignorance about the history of ethnic and religious minorities in Ukraine. Myths and stereotypes abound on all sides.

A discussion of the Holocaust also almost inevitably turns to other disasters that have befallen Ukraine in the twentieth century, including Holodomor—the policy of starvation that Stalin perpetrated against the Ukrainian countryside in the 1930s, resulting in the deaths of millions—and the 1944 deportation of Crimean Tatars. And there is the unresolved issue of the Volyn massacre, which the Polish Sejm just recently concluded was an act of genocide by ethnic Ukrainians against the Poles, a decision that many Ukrainians consider to have been politically motivated.

In this, Ukraine is not unique. According to the prominent Ukrainian historian Georgiy Kasianov, in conflating these various tragedies, Ukraine has followed the Central European model. “When [other Central European countries] were entering the EU,” he told me, “they really didn’t want to talk about Holocaust. They insisted that they themselves were victims of a double genocide: first at the hands of the Soviets, then at the hands of the Germans.”

The Vanished Civilizations

In this maze of competing genocide narratives, finger-pointing, and defensive posturing, politics overtakes history, perpetuating fear and obscuring what really matters. The most concerning part of this is that in multiethnic and multiconfessional Ukraine, it suggests that the tragedies of some of the other ethnic groups that continue to share the country with ethnic Ukrainians, such as Jews and Poles, are not considered to be part of the national Ukrainian tragedy.

To be sure, there is a desire to do the right thing. Ukraine has conducted Babi Yar commemorations on a regular basis since independence, and this year’s spurt of activity is by all estimates the largest in its history. Speaking at the Israeli Knesset last December, Ukraine’s president Petro Poroshenko said: “We must remember the negative events in history, when collaborators helped the Nazis seek the Final Solution. Following its establishment, Ukraine asked for forgiveness, and I am doing it now at the Israeli Knesset in front of the children and grandchildren of victims of the Holocaust, who experienced that horror first hand. I am doing this in front of all the citizens of Israel.”

These observations and commemorations are significant. Yet the problem is deeper than these symbolic gestures and deeper even than Holocaust awareness and education alone. Post-independence Ukraine’s history books have largely ignored the history of the country’s ethnic minorities. “Already in the early 1990s,” wrote Kasianov, “a new standard for writing national history was set … which presented the history of Ukraine as a history of ethnic Ukrainians. Other peoples who lived in the territory of contemporary Ukraine served at best as background for this ethnic-national history, and in the worst case were presented as enemies of Ukrainian statehood…. The names that were chosen to represent the national pantheon [of new national heroes] corresponded to the policy of ethno-symbolism. In the same way that the rewritten school history ignored other ethnic groups that had been part of Ukraine’s history, they were absent from the pantheon.”

[[{"fid":"69446","view_mode":"default","fields":{"field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Babi Yar Lecture","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"Participants in the youth programming at the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter's symposium on the 75th anniversary of Babi Yar in Kyiv on September 25, 2016.","field_file_source[und][0][value]":"Izabella Tabarovsky","field_file_caption[und][0][value]":"Participants in the youth programming at the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter's symposium on the 75th anniversary of Babi Yar in Kyiv on September 25, 2016."},"type":"media","attributes":{"alt":"Babi Yar Lecture","title":"Participants in the youth programming at the Ukrainian Jewish Encounter's symposium on the 75th anniversary of Babi Yar in Kyiv on September 25, 2016.","height":"1080","width":"1920","class":"media-element file-default"}}]]

In Ukraine that, in contrast to some other East European countries, remains ethnically and religiously diverse, what’s needed is an educational program that reincorporates the history of ethnic minorities that have lived side by side with Ukrainians for centuries.

At stake is whether or not Ukraine succeeds at realizing the vision of itself as a modern, tolerant nation. The examples of other countries show that to be effective, tolerance needs to become a deeply felt value and a deeply held belief that expresses itself in action. Tolerance needs to be continually nurtured and reinforced. Fifty years after Martin Luther King, racism remains part of the fabric of American society. In Poland, after the publication of Jan Gross’s book Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland, which led to a national conversation about the Poles’ role in the Holocaust, the tides have once again started turning. In Europe, xenophobic violence, including anti-Semitism, is on the rise.

Eradicating ghosts of the past takes more than declarations. It takes, first of all, encountering the other face to face, through dialogues about history and today’s problems, through programs that enhance the understanding of one another.

In a recent conversation, Vadim Altskan, a historian and senior project director at the International Archival Programs of the Mandel Center at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, observed that the new generation of Ukrainians, even those living in cities that used to be 70 to 80 percent Jewish, know nothing about that history. “An entire civilization vanished. Yet if these young people come across Jewish graves at an overgrown cemetery or ruins of synagogues, they have no idea what this is. It’s six or seven centuries of history! You can’t get rid of it. It exists. And without discussing these difficult questions, nobody will move forward.”

For Altskan, what’s at stake is the very heart and soul of the Ukrainian nation. “People need to know what happened on their earth: who lived on it, how this civilization disappeared,” he told me. “It’s like a lagoon, an empty space. And sooner or later it will need to be filled with something. If not this generation then the next one, as in Germany, will be asking itself: how could it happen, what happened?”

Reinserting the Lost Pages

Some of the events taking place in Kyiv this week take aim precisely at that. UJE’s symposium includes special programming for youth, presentations by well-known historians such as Timothy Snyder, film showings, and theatrical productions, many of them geared toward addressing some of the most painful subjects, including local collaboration with the Nazi regime. Some 190 young people have been selected to participate in the programming. Of special note is the work being done by Tkuma, the Dnipro-based Ukrainian Institute for Holocaust Studies, headed by Dr. Ihor Shchupak, which has published a number of books and teachers’ manuals to teach tolerance through Holocaust studies.

The 75th anniversary of Babi Yar has created a resurgence of interest in this part of history. A number of teachers I spoke with said that the history of the Jewish people in Ukraine is of great interest to their students.

But fears persist. There is a sense that Ukraine is still too fragile to deal with hard issues and that presenting the nation with controversial historical topics will divide it. Addressing this concern at a public lecture organized in Kyiv by the Kennan Institute, Altskan told the packed audience of historians, students, and museum workers that today’s Ukraine does not need to be afraid of its past. “If we try to cover something up, our enemies will always find it and publish it in the front pages of their newspapers. In order to deprive them of it, we must tell this story ourselves. This is what will allow us to take that ideological weapon away from our enemies.”

Notably, this history is far from exclusively tragic. The Soviet policy of de-facto Holocaust denial not only led to ignorance about events and the names of those who died. It also obscured the names of those ethnic Ukrainians and others who could by rights be considered the Righteous among the Nations: ethnic Ukrainians and members of other ethnic groups who saved the Jews. Numerous other examples of peaceful and supportive coexistence between Jews and Ukrainians as well as other national groups exist and need to be brought out and highlighted.

[[{"fid":"69451","view_mode":"default","fields":{"field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Babi Yar Memorial at Night","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"The Menorah Memorial at Babi Yar at night.","field_file_source[und][0][value]":"Photo by Izabella Tabarovsky","field_file_caption[und][0][value]":"The Menorah Memorial at Babi Yar at night."},"type":"media","attributes":{"alt":"Babi Yar Memorial at Night","height":"1080","width":"1920","class":"media-element file-default"}}]]

The Day After

The fundamental value of Holocaust studies is in the moral questions they force us to ask ourselves, and the conclusions we draw, about what kind of citizens we want to be. What would I have done had I been there? Would I have had the strength to choose the right path? Could I have seen the humanity of the victims when everybody else turned a blind eye to them?

The study of mass tragedies depends on our ability to make individual stories come alive. The history of the 6 million is in the shaking voice of an elderly woman who as a girl witnessed her Jewish classmate being taken away to be murdered. It’s in the story of a survivor who lost 20 relatives in the Holocaust and pleads with Boris Maftsir, her interviewer, to show her interview abroad in case someone survived and she could finally escape the loneliness that still crushed her decades after the war. It’s in the stories of those who rescued others, and those who today work in their own personal way to discover their town’s forgotten history or to atone for the horrors perpetrated by a larger group. The challenge for Ukrainian educators will be to help create this kind of emotional connection to the tragedy of the Holocaust, which for now remains distant for most Ukrainian schoolchildren, to evoke empathy and identification.

The measure of success of this week’s commemoration will then be what happens the day after. It is notable that much of the discussion this week is being driven by foreigners. After the distinguished foreign guests depart and the exhibitions close, Ukraine will once again be left one-on-one with its history. What will matter then is what it is that Ukrainian children are learning about their past. Will they know that Jews, Poles, and other ethnic groups were once their neighbors, living side by side with them for hundreds of years? Will they be open to learning about their culture? Will the political will exist to turn tolerance into a value that is built on education, dialogue, and joint action throughout the country?

How Ukraine as a nation chooses to answer them, what lessons it chooses to incorporate into its school curricular, its political discourse, and its historical narrative, will determine whether or not the deaths of 100,000 mean something for future generations.

The opinions expressed here are solely those of the author.