The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) emerged a winner in Germany's snap general election on February 23. It doubled its share of the vote, which signals a historic shift in the country’s political landscape. While the AfD has no path to government, its growing influence is poised to reshape German politics. These results highlight how influential the AfD has become in the public sphere.

The election followed the collapse of Germany's three-party coalition of Social Democrats, Greens, and Liberals (FDP), which was plagued by infighting. With the economy in a two-year recession, rising living costs, and a series of deadly terrorist attacks by migrants and foreign residents, the short and heated campaign centered on immigration, which many mainstream politicians framed as a security issue. Economic concerns, inflation, energy costs, and strained public finances also dominated the debate. These issues resonated with a public deeply worried about the nation’s future—83% of voters expressed concern about the country’s situation, while an all-time low of only 14% approved of the outgoing government’s performance.

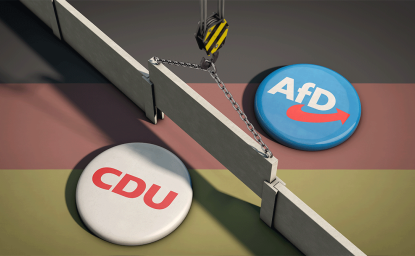

Voter turnout surged to 82.5%, the highest in a national election since 1990. The center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and its sister party, the CSU, led with 28.6% of the vote, while the AfD came in second with 20.8%, more than doubling its previous share. CDU leader Friedrich Merz is expected to become Germany’s next chancellor, but with whom he will govern remains uncertain. The most likely scenario is a narrow majority coalition with the Social Democrats; a broader coalition including the Greens is less likely. Coalition talks will begin soon, but deep policy divisions among mainstream parties suggest tough negotiations ahead. Merz aims to finalize a coalition agreement by Easter as pressure mounts to restore political stability in Europe’s largest economy.

The new government faces major domestic and international challenges. Domestically, it must address economic stagnation, rising social discontent, and growing demands for stricter migration policies. Internationally, it must promote European unity while navigating shifting US policies—especially as the Trump administration pushes for a ceasefire with Russia, bypassing Ukraine and its European allies. The absence of a centrist supermajority further complicates efforts to amend the constitution to fund critical security initiatives.

Despite its electoral gains, the AfD remains excluded from formal power as mainstream parties continue to enforce a ‘firewall’ against cooperation with the far-right. Founded in 2013 in opposition to Chancellor Angela Merkel’s handling of the Eurozone crisis, the AfD has evolved into a far-right, populist, and nativist party. It first entered the Bundestag in 2017 with nearly 13% of the vote and is now represented in fourteen of sixteen state parliaments. In the September 2024 state elections in eastern Germany, it won the state election in Thuringia and came in a close second in Saxony and Brandenburg. Classified by Germany's domestic intelligence agency as a suspected right-wing extremist group, and in three states as a confirmed right-wing extremist group, some AfD branches and members are under surveillance. Leading party figures have employed xenophobic and antisemitic rhetoric, revived Nazi-era slogans, and promoted mass deportation of immigrants. Beyond immigration, the AfD opposes military aid to Ukraine, sanctions on Russia, and EU climate policy while advocating for Germany to exit the Eurozone.

In the run-up to the Bundestag election on Sunday, the AfD capitalized on public fear following terrorist attacks, doubling down on its anti-immigration stance. The party also benefited from unprecedented, high-profile international endorsements. Elon Musk called the AfD 'Germany's only hope', while US Vice President J.D. Vance criticized German leaders for refusing to work with the far-right. Although the direct electoral impact of these interventions is unclear, they amplified the AfD’s message on social media platforms like X and boosted the party’s confidence.

The AfD not only became the second-largest party nationally but also emerged as the dominant force in all five eastern German states, where it won more votes than the outgoing governing coalition combined. For the first time, it also won majorities in two western constituencies in Rhineland-Palatinate and North Rhine-Westphalia. This surge is attributed to widespread disillusionment with mainstream parties, the AfD's skillful framing of migration as a security threat, and its exploitation of fears about terrorism, cultural integration, and strained social services. In eastern Germany, there is a strong sense of being unheard by the West, especially when it comes to migration and policies that are seen as out of touch with regional realities. The AfD's rhetoric, once seen as extreme, has gradually become more normalized, making its views more acceptable to voters who might have previously rejected them.

Although excluded from formal power, the AfD will now lead the opposition, allowing it to shape the political agenda from the fringes. The party is expected to adopt an obstructionist strategy to undermine the new government and strengthen its position ahead of the 2029 elections. It will prioritize its anti-immigration politics, likely pressuring the new CDU-led government to tighten migration and asylum law—a trend already seen with a recent CDU-initiated non-binding motion to restrict immigration that passed parliament with AfD support. The AfD's rise is also expected to hinder efforts to attract urgently needed skilled workers from abroad, particularly in regions where the party is strongest. Almost half of business association leaders report difficulties in recruiting foreign talent in AfD strongholds.

Climate policy is another area where the AfD's influence will be felt. It is the only party in the German Bundestag to outright reject the scientific consensus on man-made climate change, portraying climate action as excessive and as ideologically driven. With its growing support, the AfD adds further obstacles to effective climate action—already difficult due to the scale of the problem, competing stakeholders, business interests, and the short-term costs for long-term benefits. As the AfD gains ground, mainstream parties may become more cautious about their climate ambitions, lest they lose further voter support.

While the AfD’s rise could act as a disciplining factor, prompting mainstream parties to cooperate better and stabilize the political center, the new CDU-led government faces a difficult balancing act. To counter the AfD's growing influence, it must deliver tangible solutions to Germany's economic and social challenges. Without meaningful change, the AfD’s political clout is likely to grow stronger in the years ahead.

Author

Global Europe Program

The Global Europe Program is focused on Europe’s capabilities, and how it engages on critical global issues. We investigate European approaches to critical global issues. We examine Europe’s relations with Russia and Eurasia, China and the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa. Our initiatives include “Ukraine in Europe”—an examination of what it will take to make Ukraine’s European future a reality. But we also examine the role of NATO, the European Union and the OSCE, Europe’s energy security, transatlantic trade disputes, and challenges to democracy. The Global Europe Program’s staff, scholars-in-residence, and Global Fellows participate in seminars, policy study groups, and international conferences to provide analytical recommendations to policy makers and the media. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Germany Post Election: Conservatives and Far-Right Enjoy Electoral Success

Change in the Ballot Box in Africa

In Germany’s Elections, America was an Issue