Explainer: Jihadist Movements in 2021

A year-end briefing by Daniel Byman, a professor at Georgetown University and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

A year-end briefing by Daniel Byman, a professor at Georgetown University and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

For the global jihadist movement, the most notable event of 2021 was the defeat of U.S. forces in Afghanistan and the Taliban takeover there. Otherwise, the year largely marked a continuation of past trends. As in 2020, al Qaeda and the Islamic State did not conduct or even inspire a successful terrorist attack on the United States. Data for 2021 are still being gathered, but the scale of jihadist activity in Europe has also declined in recent years.

By contrast, the groups were far more active in Muslim-majority countries. Al Qaeda affiliates and Islamic State “provinces” were fighting in the Maghreb, South Asia, Somalia, Syria, Yemen, and other areas. Many of these affiliates have gotten weaker, including al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). AQAP helped facilitate the last successful jihadist attack on the United States – the shooting at Naval Air Station Pensacola in December 2019. AQAP was the most active affiliate in conducting anti-Western international terrorism. The affiliates are largely locally focused, consumed with civil wars and regional politics and less involved in anti-Western terrorism.

An important exception to this relatively steady state was the victory of the Taliban in Afghanistan. This was a clear win for the jihadist movement, demonstrating (to them at least) that persistent struggle against the United States and its allies produces victory. In addition, al Qaeda and the Taliban remain close, and the Taliban will probably continue to offer sanctuary to al Qaeda members. Exact numbers are elusive, but the United Nations reported that 400 to 600 al Qaeda members fought with the Taliban as it was approaching victory.

But a return to the pre-9/11 level of threat is not likely. The Taliban, as well as its Pakistani allies, has many reasons to stop al Qaeda from using Afghanistan as a base for anti-Western terrorist attacks, and U.S. and allied counterterrorism capabilities are far stronger than they were in the pre-9/11 era.

The constant U.S. and allied efforts to kill senior jihadist leaders continued in 2021. France, for example, reportedly killed Adnan Abu Walid al Sahrawi, who headed the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), and the United States has conducted successful strikes against jihadi leaders in Syria and Yemen, among other countries.

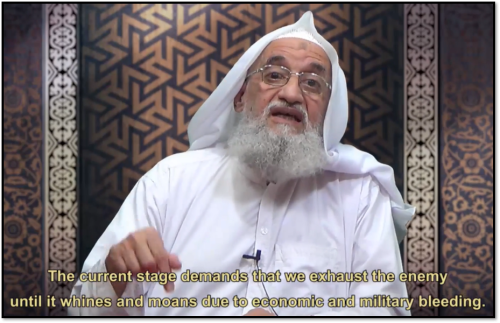

One important question is the status of longtime al Qaeda leader Ayman al Zawahiri. Rumors swirled that Zawahiri had died. His appearance in a video released in September quelled some of these rumors, but Zawahiri’s statement was dated—he did not comment, for example, on the Taliban victory despite the movement’s centrality to al Qaeda for decades. His absence from the day-to-day, or even the month-to-month, of many jihadist struggles suggests that he is exercising at best limited control over the movement.

Sunni jihadism poses a limited threat to the U.S homeland, but it remains a major threat to many governments in Muslim-majority countries. Since 9/11, jihadist groups overseas have had little success orchestrating attacks on the U.S. homeland—foiled by better domestic defense, global intelligence cooperation, and disruption of their sanctuaries and leadership structures. In both the United States and Europe, however, individuals inspired by jihadism remain a particular concern and sporadic attacks are likely to continue in the coming years.

In Muslim-majority countries, however, there are numerous branches of al Qaeda and the Islamic State that pose dangerous threats to regional governments and local stability. In many cases, such as Yemen and Nigeria, jihadist groups are participants in broader, bloody civil wars that are killing hundreds of thousands of people. In the Horn of Africa, groups like the Shebaab are conducting attacks on neighboring states like Kenya, widening the conflict zones.

From a U.S. point of view, the importance of many of these conflicts beyond humanitarian concerns is questionable. Mali, Somalia, Yemen, and many other countries are of negligible strategic importance, and the Biden administration’s pivot to Asia further reduces the U.S. focus on the Middle East.

Al Qaeda- and Islamic State-affiliated groups do not appear poised to topple governments in the region. But they do contribute to regional instability and worsen the already-bloody civil wars in the area.

The remnants of the Islamic State that are present in Iraq and Syria remain one top concern. They do not appear to be prioritizing international terrorism, but they are a threat to Iraq’s stability, particular at a time when its democratic institutions are in a fragile state. Islamic State violence heightens sectarian tension, weakens the legitimacy of the government, and otherwise poses a threat to an important regional state.

The return of the Taliban to power in Afghanistan also increases the risk from al Qaeda, with many uncertainties about how this will shape the future course of the movement. A particular concern is Taliban and al Qaeda support for other jihadist movements in South Asia. In the past, Pakistan has worked with the Taliban to use Afghanistan as a launching pad for jihadist attacks on India and for training jihadist groups.

Al Qaeda maintained the loyalty of affiliates in the Maghreb, Somalia, Yemen, and elsewhere despite the challenge posed by the Islamic State – a considerable accomplishment. But the extent to which it controls its affiliates is constantly in question. These groups at times mouth al Qaeda propaganda, but their agendas and actions are mostly (but not entirely) local. Al Qaeda has long struggled to control its affiliates. Some key groups, such as its former affiliate in Syria, Jabhat al Nusra, rejected the core – while others, such as the Islamic State, became deadly rivals. Other groups like al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb use the al Qaeda brand but do not substantially shift their targeting.

The Islamic State brand has lost some of its allure due to the collapse of the caliphate. In addition, many of its “provinces” have struggled militarily, with significant declines in once-promising Libya.

The biggest success for the Islamic State in 2021 was its province in Afghanistan, the Islamic State Khorasan (ISK or ISIS-K). Ironically, the success of the Taliban, an enemy, helped ISK in several ways. Ending the U.S. military presence removed one important ISK enemy. In addition, ISK is now positioned to attract those disgruntled with the Taliban’s leadership, even if those individuals reject ISK’s long-term goals. Nevertheless, ISK will struggle in the face of Taliban pressure, particularly as the Taliban no longer is devoting the vast majority of its efforts to fighting the United States and the U.S.-backed government in Afghanistan.

With the important exception of the withdrawal from Afghanistan, the United States and its allies largely continued their mix of military training, leadership strikes, and other efforts to keep jihadist groups down.

Perhaps more important than military strikes, however, is the global intelligence effort the United States orchestrates against these groups. For the United States and Europe, this cooperation has greatly hindered efforts by al Qaeda and the Islamic State to conduct attacks in their countries. In addition, improved domestic intelligence and greater vigilance have made these governments more effective in stopping homegrown extremism.

Daniel Byman is a professor at Georgetown University and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. His latest book is Road Warriors: Foreign Fighters in the Armies of Jihad. Follow him @dbyman.

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more