“Where have you been TakenoLAB?” Cedrick John asked in the original poem he performed at the Sub Granting Ceremony at the TakenoLAB ICT Academy. The poem went on to list what TakenoLAB has accomplished: “made our dreams come true,” “taught us skills and entrepreneurship,” and “took us from zero to hero.”

TakenoLAB is a school of technology that offers courses and training to refugees and Malawians. Located just outside the gates of the Dzaleka refugee camp in the Dowa District of Malawi, the school was founded in 2015 by Burundian Remy Gakwaya who lived in the camp as a refugee for more than two decades prior to being resettled in the United States in 2022. TakenoLAB continues to thrive under Gakwaya’s remote supervision and the local direction of Deborah Ntakirutimana, a Burundian who has been a refugee since she was only a few months old—her whole life.

TakenoLAB’s training is for everyone, regardless of nationality or refugee status. Their courses, all offered at no cost, include digital skills, e-lancing, and entrepreneurship.

I visited TakenoLAB when I came to the camp for the first time in November 2021 to attend the Tumaini Festival, an impressive multi-day event that attracts thousands of visitors to the camp each year. Tumaini’s founder and visionary is Trésor Nzengu Mpauni (aka Menes La Plume), a refugee from the Congo who has won international recognition for this innovative project. The festival is packed with music, dance, poetry, and theater performances along with the sales of visual arts and foods by those who are and who are not refugees.

The Tumaini Festival was the inspiration for my book project, My Culture, My Survival: Arts Initiatives by Refugees for Refugees. Since attending the festival, I have been traveling to different countries documenting the agency and creativity of displaced people who use the arts to do something positive for themselves, their communities, and their host countries. Refugees are too often stereotyped and maligned, but my project highlights that displaced people are smart, creative, fun, thoughtful, and loving. They cook, eat, laugh, lead, socialize, learn, read, write, sing, dance, paint, tell stories, and fall in love. As with anyone else, they also fight, struggle, grieve, cry, and feel despair.

In 1994, the Malawian government converted a former prison near the capital city of Lilongwe into a camp to provide refuge for thousands of people fleeing the civil war in neighboring Mozambique. Dzaleka, run as a partnership between the government and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, or UNHCR, has since grown into a large camp and thriving small city of more than 52,000. The majority of its residents currently are from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Burundi.

Xenophobia and anti-refugee sentiment are rampant in Malawi. In a country with a high level of poverty, many Malawians resent refugees because of the social services and economic support they believe refugees receive.

Tumaini means “hope” in Kiswahili. As with any arts festival, it is fun. But even more importantly, it brings people into the camp. Visitors who may have had little previous direct contact with refugees have the opportunity to interact with camp residents not just as refugees but as fellow human beings who have talents and skills and are welcoming hosts. In as much as the festival is about promoting arts and culture, Mpauni’s vision is to change people’s attitudes toward refugees and promote refugee advocacy.

Refugees living in Dzaleka do receive some humanitarian support, which is constantly shifting. In 2024, each individual receives about $5 per month along with other occasional handouts. The amount does not cover anywhere near what an individual or family needs to survive, much less thrive. Malawi refugee laws are restrictive. Unlike their Malawian citizen counterparts, refugees cannot legally leave the camp for more than 24 hours without authorization, do not have access to land for farming, cannot legally work, and cannot apply for citizenship. Camp residents do what they can to generate bits of income here and there to make ends meet.

UNHCR resettles a small number of Dzaleka residents each year in third countries, mostly Canada, Australia, and the United States. However, the demand is far greater than the opportunities. Many camp residents have lived in Malawi for 10-30 years. Returning to their home countries is dangerous and not an option. Many young people, such as Ntakirutimana and her younger siblings, left when they were very young or have never been to their home country. A poignant memory of my first visit to the camp was when her younger sister Divine Irakoze, who was born in a refugee camp in Tanzania and is stateless, rested her head in her hands and sighed, “I just want a nationality, any nationality.”

Within this difficult environment where feelings of despair are palpable, creativity and entrepreneurship nevertheless thrive. TakenoLAB is only one example among hundreds of refugee-led initiatives intended to create opportunities and better the lives of camp residents. The projects range from youth empowerment, education, mental health support, occupational training, religious worship, disability programs, community and peace building, conflict resolution, and arts and cultural activities.

From 2021-2023, I coordinated the Dzaleka Art Project with youth in the camp. It is a community-based collaborative project that documents some of the creative, entrepreneurial initiatives of camp residents engaged in the arts. This website offers a rich tapestry of talent, creativity, and leadership within the camp, especially among youth.

On August 2, my first day back to Dzaleka refugee camp during my 2024 visit on, I was honored that Ntakirutimana invited me to participate in the TakenoLAB ceremony. Given the negative attitudes of many Malawians, it is significant that refugees and Malawian citizens benefit from TakenoLAB’s offerings. On this day, 25 students, refugees and Malawian citizens alike, celebrated the completion of a free 6-month course in entrepreneurship. For their final projects, each produced a business proposal. The top 10 were awarded $1,000, a significant amount that they could use as capital to launch new business ideas, mostly related to agriculture.

This event was only the beginning of a lively week of documenting refugee-led initiatives by Dzaleka residents including artistic and cultural initiatives, and classes that aim to increase refugee self-reliance.

On August 3, I attended Miss Culture Dzaleka, the first in what is expected to be an annual beauty pageant. Some were wearing smart businesses suits and others were in sleek long formfitting dresses, the young contestants balanced on elegant high heels.

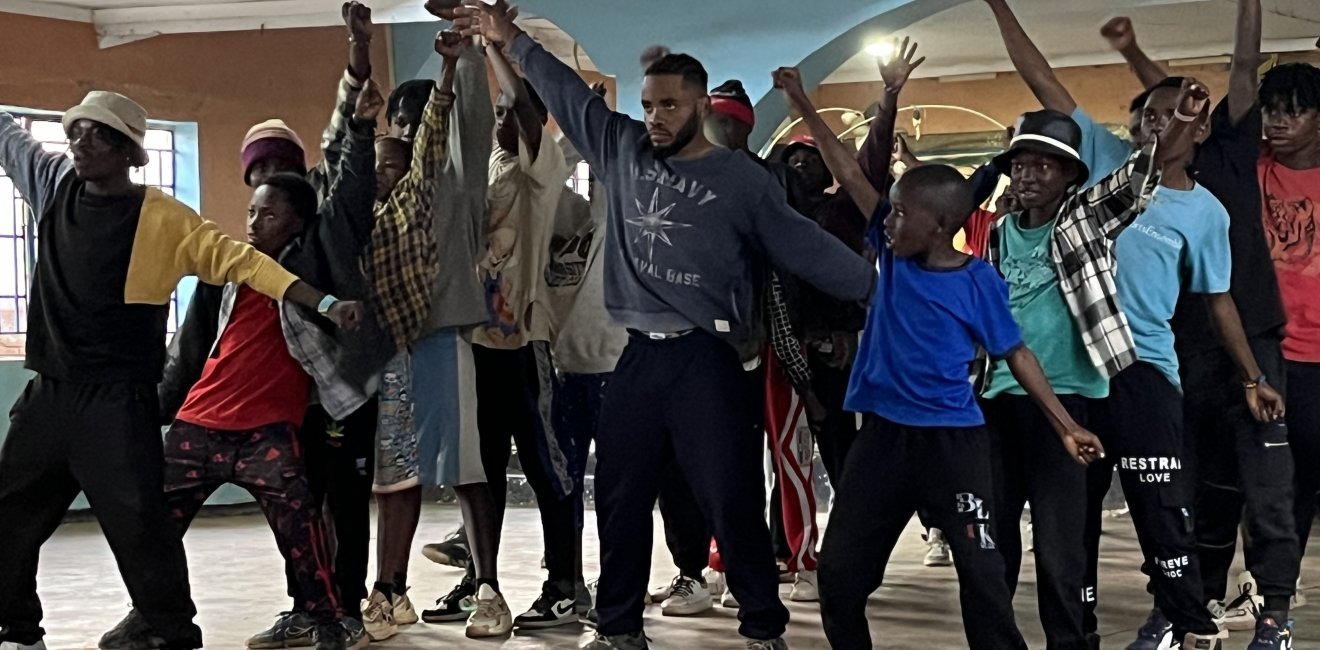

In the morning of August 6, I joined the Umoja Women Craft, an association of fifteen women, mostly between the ages of forty and sixty who weave Burundian style traditional baskets from sisal and colorful shredded plastic bags to earn income and conserve a cultural tradition while forced to live far from home. That afternoon, I attended the rehearsal of Indengabaganizi, a Rwandan traditional dance group. Blaise Nyonguru and Fabrice Bizimana, young men with little direct knowledge of their own traditions, created the troupe for young Rwandans in the camp to learn about and participate in a culture from which they are far removed.

On August 7, I visited David Bin Wakandwa at the music production studio that he runs with his friend Fadhili Aoci. The two young Congolese men have been developing their skills through online courses and YouTube instructional videos, and they procure bits and pieces of equipment as they can. The business promotes music in the camp by enabling musicians to produce recordings, while also generating income for Wakandwa and Aoci to sustain their families.

That afternoon, I attended a free photography class offered by Congolese photographer Primo Luanda Bauma. Many young people in the camp struggle with having little to do and having no hope for their futures. Bauma started this initiative to occupy youth, give them an artistic means to express themselves, and offer training that could potentially enable them to make some money. It also helps him personally. Having been uprooted from his life and having few opportunities to work in the camp, helping other young refugees gives Bauma’s life meaning and direction.

On August 8, I visited Salama Africa. Congolese brothers Toussaint and Fred Farini started it in 2014 because they knew that young camp residents had limited opportunities for their futures. Loving the arts themselves, they created a rigorous dance group that became famous in the camp and in Malawi, helping to shift positively the narrative about refugees in the country. Salama Africa has given young dancers visibility and a way to make money. It has since become a thriving organization that has received international attention for its work developing professional dancers along with providing training in drawing, photography, videography, technology, and many other skills.

What I experienced in this short week is only the tip of the iceberg of leadership and entrepreneurism in the camp.

The guests of honor at the TakenoLAB ceremony included top leadership of the camp and of the Dowa District. In her speech, Priscilla Kalumo, the UNHCR Education Officer, emphasized that TakenoLAB is adding critically needed capacity to the camp. It is helping UNHCR and the Malawi government reach their target goals of increasing tertiary education and training opportunities for camp residents and Malawi citizens. Doroth Mzungu, the Educational Principle of Dowa District, ended her speech thanking TakenoLAB “for helping development in Malawi and contributing to the government’s goals.”

There is a common assumption around the world that refugees drain the social and economic fabric of their host countries. Yet, refugees are people who actively do what they can in their new environments to meet their needs and contribute to their refugee and host communities. As is evident from the vibrant activities generated by Dzaleka residents, the leadership, talents, and skills of displaced peoples are a resource that should be recognized, nurtured, and promoted by host countries because they are beneficial to refugee and host populations alike.

Author

Professor, George Mason University

Refugee and Forced Displacement Initiative

The Refugee and Forced Displacement Initiative (RAFDI) provides evidence-based analyses that translate research findings into practice and policy impact. Established in 2022 as a response to an ever-increasing number of people forcibly displaced from their homes by protracted conflicts and persecution, RAFDI aims to expand the space for new perspectives, constructive dialogue and sustainable solutions to inform policies that will improve the future for the displaced people. Read more