The Role of “Ethnic” Cafes in Migrants’ Integration in Moscow

Interview with Vera Peshkova, Former Galina Starovoitova Research Scholar, and Researcher, Institute of Sociology, Russian Academy of Sciences, on May 30, 2014. Kennan Institute project “The Role of Immigrant Infrastructure in the Migrants' Integration and the City Space Transformation (on the Case of "Ethnic" Cafes in Moscow).”

Malinkin: How new a phenomenon are the “ethnic” cafes in Moscow? And what caused them to emerge?

Peshkova: There are a few factors which influenced this. First, migration [to Moscow] has been growing over the last 10 years. More and more people have been coming, and those that came earlier are now more integrated, have adapted more, and know the local rules better. Some of them have also become wealthier in this period. While during their first years they had to earn and send money home, over the last 3-4 years some of them within the Kyrgyz and Uzbek communities (I focus on Central Asian migrants for my research) are doing better and have more disposable income to patronize cafes or even open their own. It is also important to note that a few hundred thousand Kyrgyz migrants have gotten Russian citizenship. This gives them more possibilities compared to the Uzbeks, for example, who can't get Russian citizenship so easily. As the Kyrgyz build their capital, they have money to invest in building cafes as well as send home. My colleagues in St. Petersburg have similar findings there as well – they are seeing that more migrants have more free time and more money for pleasure.

So some migrants are starting to break into the café and restaurant scene - did something happen that allowed the market to open up to them?

No, I believe that it's mostly economics. There is a combination of informal and formal rules for the cafes. Many cafes appear near markets, and there is no particular diversity strategy for business. There are just more and more newcomers, and in their growing numbers they have more possibilities now to start their own businesses.

Are most of the ethnic cafes in Moscow near markets?

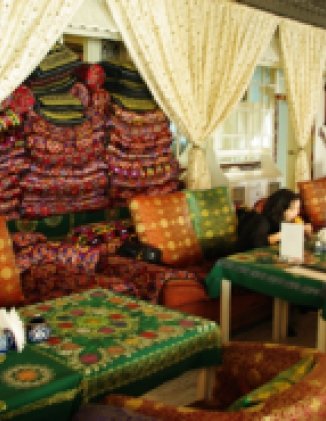

There are a lot of these cafes around markets, but this is not the only place they appear. They are also near railway stations, big highways, gas stations, and especially outside of Moscow on the MKAD. It's easier to open these cafes, and teahouses in particular, on the big highways that cross the MKAD. As for Kyrgyz café-clubs, they tend to be near metro stations, but not in the city center, and often in more “hidden” places.

Besides Central Asian migrants, who you focus on, are there other ethnic migrant groups that are opening more cafes?

There are a lot of cafes with Caucasian cuisine - especially Azerbaijani. In the case of Azerbaijani cafes, run by Azerbaijani businessmen, they often started their businesses at bazaars or markets, in particular at Chirkizovskiy Market in Moscow. But many of the Azerbaijani migrants arrived in Moscow earlier than the Kyrgyz or Uzbek migrants, so they have had more time. Also, business in Moscow in the 90s was different – it was more flexible. There were more informal rules and more economic niches were available because the Moscow market was so diverse.

Do the Azerbaijani cafes tend to have more Russian patrons? Or are they more targeted at migrants?

They don't have special intentions. They are just businesses, trying to make a profit and welcoming everybody.

This is in contrast to how you have described the Central Asia cafes as places for migrants to see each other, to have a community. Do other migrants - from the Caucasus for example - meet in other places in Moscow?

Many of the Caucasian migrants go to Uzbek (“chaikhana”) because they tend to have halal food and drinks (non-alcoholic). Muslims from many different ethnic backgrounds eat in Uzbek teahouses. Azerbaijani and other Caucasians like to visit Azerbaijani cafes as well, but often the theme of the restaurant is broader – Caucasian - not just Azerbaijani themed. These cafes tend to be more expensive, and they usually have alcohol. The Azerbaijani and Armenian migrants tend to be more established, and many of them are citizens of Russia. Sometimes it's difficult to draw the line between migrants and citizens. Some Kyrgyz are such new citizens that we still refer to them as migrants in our research[1]

At what point are these migrants no longer "migrants"? After 5 years? 10 years? How long would you say most of the people were staying?

I don't have that information for this project, but just looking at data from other projects on migrants in Moscow, it's a very complicated question regarding how they self-identify, if they consider themselves migrants or not, even if they have citizenship and whether there is any connection between being a citizen and feeling like you are a migrant or not. According to another project I am involved in, many migrants, even if they have citizenship, continue to go home every year - they go home for a few months and come back, or even for a full year and come back. So it’s a really flexible number – often they are still migrants. Many of the Kyrgyz, for example, intend to return home for their pensions. They might be trying to earn money in Moscow for a new car, but they don't want to stay in Moscow. They will go home for their pensions. It’s a really complex question - how we understand who is a migrant.

Overall, how well would you say migrants are integrating in Moscow? Do the ethnic cafes help them to integrate? Why or why not?

Cafes oriented towards migrants attract them with the opportunity to enjoy both “ethnic,” traditional practices (e.g, to listen to their national music, eat their national food, and speak their native language), and new customs that they have learned in Moscow (for example, the fast-food culture, going on blind dates, etc.). These cafes play a double role in Moscow’s social space: they simultaneously unify and marginalize. On the one hand, they can aide in the social exclusion of migrants, especially in the Kyrgyz case, because the cafes, along with tickets agencies, brokerage agencies, specialized media, and pharmacies, form an “alternative” social service sphere in Moscow. On the other hand, the cafes become a sort of mediation zone, facilitating the incorporation of migrants into Moscow’s urban space. The mere existence of the cafes can be considered an indicator of the adaptation of migrants in Moscow.

Mary Elizabeth Malinkin

Matthew Rojansky, Director, Kennan Institute

[1] A project which was supported by RHSF (Российский гуманитарный научный фонд) grant №13-33-01032.

About the Authors

Kennan Institute

The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Russia and Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the surrounding region though research and exchange. Read more