On June 26, the Wilson Center’s Mexico Institute hosted a discussion about the current status and future prospects of Mexico’s justice sector reform. Since 2008, Mexico has been implementing a series of reforms that will transform the nation’s criminal justice system to make it more transparent and accountable, thereby improving the nation’s administration of justice and public security. Here are key aspects of that reform:

- Introduction of oral trials using adversarial procedures, the creation of alternative sentencing options, and alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms;

- Greater emphasis on the rights of the accused (i.e., the presumption of innocence, greater due process guarantees including adequate legal defense);

- Modifications to police agencies and their role in criminal investigations;

- Tougher measures for combating organized crime.

According to Wilson Center Global Fellow and panelist David Shirk, central to Mexico’s reforms, “is a package of ambitious legislative changes and constitutional amendments…that are to be implemented throughout the country by 2016. Together, these reforms touch virtually all aspects of the judicial sector, including police, prosecutors, public defenders, the courts, and the penitentiary system.”

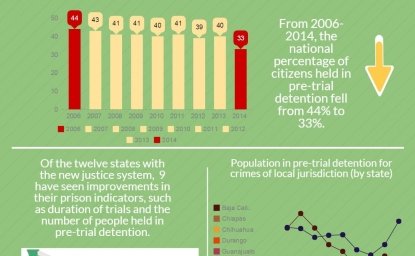

With the deadline for implementation just around the corner, an update on the reform’s status seems timely. As the map below shows, twelve of Mexico’s 31 states and the Federal District have adopted the new judicial system. Of the remaining states, 14 have reformed their constitutions and adopted the new criminal procedures but have not yet fully implemented the reforms. Only 6 states have yet to begin the reform process. Mexico is also in the process of adopting a unified criminal code that all state and federal courts will have to follow. Overall, it’s been an ambitious and complex process of reformation that is still unfolding.

In his presentation, David Shirk argued that while the introduction of oral trails in Mexico’s justice system are important, in his view, the most transformative aspect is the shift from an “inquisitorial” model of justice – where trails and judgements are made based on the written record – to an adversarial system of justice – where defense attorneys and prosecutors argue their cases before a judge in open court. This system, for the first time, also allows for alternative sentencing mechanisms, such as a juicio abreviado, or plea-bargaining. The panel was hopeful that these alternatives would reduce the number of cases heard in court, and thereby reduce court congestion and back-log.

A second key factor in the reform’s success is the transformation of law school curriculum to train new and future officers of the courts, as well as retrain those already in practice. According to David Shirk, a great deal of money and time still needs to be invested in training, as well as professional oversight of many of the current and future officers of the court that will be involved in putting the reforms into practice:”We have not properly prepared the other actors that operate in the new criminal justice system.” Ultimately, the success of the reforms will depend on revising the educational requirements and vetting procedures for applicants to practice law under the new system. Moreover, since federal, state, and local law enforcement officers have been delegated more responsibility within the reformed system, such as responsibility for the protection of the crime scene, the vetting procedures in each branch of government will also need to be reevaluated to incorporate higher standards of transparency and accountability.

To date, one important element of that retraining has been exchanges between law schools and legal experts from other countries (including the U.S.) with experience in the adversarial justice system. Still, according to David Shirk:

“Efforts to promote professionalism among lawyers are needed, as they will be primarily responsible for ‘quality control’ in the Mexican criminal justice system. Although Mexico has recently adopted a new code of ethics, Mexican lawyers are not presently required to receive post-graduate studies, take a bar exam, maintain good standing in a professional bar association, or seek continuing education in order to practice law. All of these are elements of legal professionalism that developed gradually and in a somewhat ad hoc manner in the United States, and mostly in the post-war era.”

Finally, according to another panelist, Leoba Castañeda, the Dean of the Law School at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, in order to ensure that the reforms are being implemented there should be a transparent evaluation done within five years of the 2016 deadline: “We have to change the way we administer justice now, but what is equally important is that in four or five years, an evaluation done.” With time running out on the 2016 deadline, it will be up to the new generation of lawyers in Mexico to ensure that these reforms are taken seriously and implemented properly in the future.