Al Qaeda & ISIS 20 Years After 9/11

Twenty years after the 9/11 attacks, the global jihadist movement has more fighters in more countries than ever before.

Twenty years after the 9/11 attacks, the global jihadist movement has more fighters in more countries than ever before.

Katherine Zimmerman is a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and an adviser to AEI’s Critical Threats Project.

Twenty years after the 9/11 attacks, the global jihadist movement has more fighters in more countries than ever before. The way Salafi-jihadi groups, including al Qaeda, have sought to achieve their aims has evolved since 2001, but the core belief that violent jihad must be waged to restore Islam in Muslim societies has not changed.

Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda had prioritized the fight against the United States and the West—the “far” enemy—while delaying attacking the regimes in Muslim-majority states—the “near” enemy. By contrast, Abu Bakr al Baghdadi and the Islamic State prioritized the near war over the far war, while still seeking to inspire attacks in the West.

The United States and its allies, meanwhile, developed sophisticated counterterrorism and intelligence capabilities to disrupt and prevent terror attacks. The threat from the global jihadist movement subsequently shifted in new directions. In 2021, key trends included:

The Taliban’s announcement of its government for the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan” on September 7, 2021, heralded a new era under the fundamentalist interpretation of Sharia, or Islamic law, that Salafi-jihadi groups support. Salafi-jihadi groups had already celebrated the Taliban’s victory over the U.S.-backed Afghan forces after the U.S. and NATO withdrawal. The global movement has been reinvigorated, taking the Taliban’s success as proof of a winning strategy.

Moreover, foreign fighters have reportedly traveled to Afghanistan, adding to the thousands already present in the country. The Taliban’s Afghanistan will almost certainly provide Salafi-jihadi groups a sanctuary to strengthen themselves for their own fights globally.

AQAP: al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

ISIS: Islamic State in Iraq and al Sham

AQIS: al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent

ISKP: Islamic State Khorasan Province

AQIM: al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb

ISSP: Islamic State Sinai Province

ISCAP: Islamic State Central Africa Province

ISWAP: Islamic State West Africa Province

ISEA: Islamic State East Asia

JNIM: Jamaat Nasr al Islam wa al Muslimin

ISGS: Islamic State in the Greater Sahara

Salafi-jihadi groups globally have proven to be resilient since the Global War on Terrorism began in 2001. All groups have been able to recover from key leadership losses. They have increasingly embedded in local conflicts, which has required them to respond to shifting dynamics within insurgencies. This adaptation as well as the targeting of externally oriented terror cells by the United States and its partners has degraded the components of groups focused on the global jihad.

Salafi-jihadi groups have achieved some of their objectives despite pulling back from the far war. They have retained the ability to reconstitute even in theaters where counterterrorism campaigns have weakened them. Groups have held together because the political and socioeconomic conditions that originally drove recruitment remain in place. Moreover, they have capitalized on popular grievances and local instability worsened by the coronavirus pandemic.

Foreign fighters who have returned to their homelands from Iraq and Syria pose a looming threat. They are better situated to conduct local terror attacks or travel to join other Salafi-jihadi groups. These fighters may also travel to Afghanistan as it again becomes a destination for the development of a Salafi-jihadi cadre.

The influence and activities of Salafi-jihadi groups have spread across the African continent, catalyzed in part by local conditions and weak governments and security forces.

In East Africa, al Shabaab, which controls parts of south-central Somalia, continues to challenge Somali security forces and African Union peacekeeping troops. It has exploited Somali security forces’ preoccupation with election-related activities, a partial drawdown of African Union peacekeeping forces, and the withdrawal of U.S. military forces from Somalia to expand on the ground. Al Shabaab has targeted US military forces and foreign interests in the region and has sought the capability to target commercial aviation.

The Islamic State branch has a small footprint in Somalia and serves as a crucial link between the Islamic State Central African Province (ISCAP) in Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Islamic State leadership in Iraq and Syria.

The Islamic State operates as ISCAP in Mozambique and in the DRC, though links between the two groups are not clear. In 2021, ISCAP sparked a full-fledged insurgency in northern Mozambique, including seizing control of key towns. Regional states are responding to ISCAP’s threat by deploying troops to Mozambique to counter the group. ISCAP expanded its area of operation in the DRC and has recruited foreign fighters to its insurgency. In August 2021, the Congolese government accepted U.S. counterterrorism assistance, which may limit ISCAP’s ability to grow. Nonetheless, ISCAP’s insinuation into local insurgencies in both Mozambique and the DRC may help it continue to strengthen.

In North Africa, the Islamic State Sinai Province (ISSP) has withstood Egyptian military pressure but has not strengthened significantly. Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) continues to operate from safe havens in southwestern Libya. AQIM has prioritized the success of Jamaat Nasr al Islam wa al Muslimin (JNIM) by directing resources into the Sahel. AQIM also works closely with the Tunisia-based Uqba ibn Nafa Brigade. Cells linked to the Islamic State have been dismantled in Algeria, Libya, and Morocco. Anecdotal evidence indicates some returnees from Iraq and Syria have sought to join groups in the Sahel.

In West Africa, Salafi-jihadi groups have expanded and strengthened. JNIM, primarily based in Mali, has spread into neighboring countries to include recruiting cells in Senegal and attack cells in Cote d’Ivoire, as well as threatening Benin, Ghana, and Togo. It has maneuvered within local conflicts in Mali, taking advantage of inter-communal violence to grow its influence within different communities. The group retains strong ties to AQIM and has proven resilient against counterterrorism operations.

The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), operating primarily in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, has prioritized the conduct of large-scale attacks against security forces and community-based armed groups. ISGS and JNIM have come into direct conflict as they have each expanded. Regional counterterrorism forces, backed by a French-led special forces mission, have targeted the leadership of these groups but have not reduced their influence on the ground.

The Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) has grown as it has weakened a rival Salafi-jihadi group, Boko Haram, from which it splintered originally. The Islamic State claims ISGS attacks under ISWAP’s name, though—like ISCAP Mozambique and DRC—the two organizations are geographically distinct. ISWAP has absorbed some Boko Haram factions and has pursued a more successful strategy than its rival at building support within local communities.

Sustained counterterrorism pressure, particularly in Iraq and Yemen, has limited the growth of the Islamic State and weakened al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). Regional instability, however, has enabled Salafi-jihadi groups to survive and creates an environment for them to grow again.

In Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State in Iraq and al Sham (ISIS) remains active even though ongoing counterterrorism operations have weakened it. In eastern Syria, ISIS has been reconstituting its combat capabilities and transitioning to guerrilla warfare. Northwestern Syria, which is primarily under the control of Hayat Tahrir al Sham, another Islamist movement, serves as a sanctuary for ISIS families and a key transit point to enter Turkey. In Iraq, ISIS has reduced strength but continues to operate attack cells, including in Baghdad and the surrounding area.

In northwestern Syria, Hayat Tahrir al Sham has portrayed itself as “moderate” but still embraces Salafi-jihadi ideology. It has targeted Hurras al Din, also known as al Qaeda in Syria, seeking to consolidate control and crack down on those actively focused on the global jihad within its territories. Hurras al Din was weakened in 2020 but still draws hardline recruits.

In Yemen, AQAP has strengthened over the course of 2021 after counterterrorism pressure from the United States and the United Arab Emirates had significantly weakened it. AQAP began a counteroffensive against UAE-backed troops in southern Yemen and continued to clash with al Houthi fighters in central Yemen. Counterterrorism operations never removed AQAP from its historical sanctuaries, which prevented its defeat. The Islamic State branch operating in central Yemen has remained weak.

Salafi-jihadi groups in Afghanistan and the region had been positioning for the expected withdrawal of U.S. and NATO forces from Afghanistan in August 2021. They have been strengthening on the ground despite counterterrorism pressure. Counterterrorism efforts have disrupted Islamic State-linked cells in Indonesia and the Philippines. They have not successfully stopped all attacks, however.

In Afghanistan and Pakistan, the Taliban has provided al Qaeda and AQIS with support for their operations. Al Qaeda’s presence expanded in Afghanistan throughout the first half of 2021, and AQIS has successfully integrated into the local insurgency, making it difficult to separate it from the Taliban. The Haqqani Network, whose leader is a top official in the Taliban, has continued to facilitate regional cooperation among other Salafi-jihadi groups. The Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, which had been weakened by Pakistani counterterrorism operations, may have begun to reconstitute in the Pakistani tribal areas from its sanctuaries in Afghanistan.

The Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) was weakened in 2020. But it stood to gain new recruits in 2021 by presenting itself as a harder line alternative to the Taliban. German authorities disrupted a Tajik terror cell with ties to ISKP plotting attacks on U.S. forces in Germany in 2020.

In Southeast Asia, groups linked to the Islamic State continue to pose terror threats, but authorities have been able to disrupt some plots. Jamaah Ansharut Daulah claimed credit for the Palm Sunday bombing in Makassar, Indonesia, in March 2021. In February that year, Philippine security forces disrupted a cell of women purportedly planning suicide attacks targeting soldiers.

Both al Qaeda and the Islamic State have survived despite the elimination of many senior leaders by the United States and its partners. Ongoing counterterrorism pressure, however, has limited the ability of senior leaders to communicate with their followers. In the case of the Islamic State, this has weakened control over branches and has resulted in the delegation of some of its authority. Al Qaeda’s already decentralized structure limits the impact, but the absence of senior leaders within affiliates, such as AQAP, has resulted in their weakening.

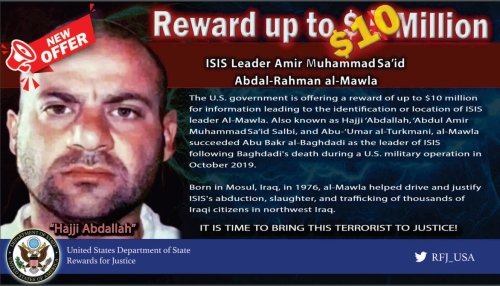

As of September 2021, key Salafi-jihadi leaders included:

Groups such as al Shabaab, AQAP, and ISIS have pursued external attack capabilities but have not conducted a terror attack in the United States since the December 2019 Pensacola shooting.

U.S. forces deployed on counterterrorism operations, however, have been targeted. The deadliest attack occurred on August 26, 2021, when as ISKP suicide bomber detonated a device in Kabul, Afghanistan. Al Shabaab has also targeted US forces in Somalia and Kenya. Both al Shabaab and ISIS have killed Americans during U.S.-supported counterterrorism raids: al Shabaab fatally wounded a CIA officer in November 2020 and ISIS killed two special operations Marines in March 2020.

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more