The time has come for the Biden administration to rethink its policy toward Hamas. Even the Israeli military has come to the conclusion that it cannot be eliminated and will remain a major political force after a ceasefire is concluded in the Gaza war.

Such a rethink will not be easy. Both the United States and Israel are committed to the total destruction of Hamas after its October 7 incursion into the Jewish state that left 1,200 Israelis dead and 250 others seized as hostages. They also swore to ban it from playing any role in the future governance of the Gaza Strip, over which it had ruled since 2007.

Shift in IDF perspective

After nine months of a campaign to crush Hamas’ army of 40,000 guerrillas and destroy its 350 miles of underground tunnels, on June 19 the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) broke with the government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to declare publicly the total destruction of Hamas was not possible. The IDF’s official spokesman, Rear Admiral Daniel Hagari, said in an interview on Israeli television that such a goal amounted to “throwing sand in the eyes of the public.” He added, “Hamas is an idea. Hamas is a party. It’s rooted in the hearts of the people. Anyone who thinks we can eliminate Hamas is wrong.”

The conundrum is how to deal with a group both the US and Israeli governments long ago branded a terrorist organization for its commitment to the destruction of Israel and now its responsibility for the deadliest incursion into Israel since its founding 76 years ago.

There is, however, a precedent for a Palestinian “terrorist” group and Israel changing their spiteful view toward each other: Fatah, the dominant faction of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) under the leadership of Yasser Arafat from 1969 to 2004. For many years, it embraced terrorism as a tactic of warfare against Israel and, at one point, even the United States.

In 1971 the PLO, set up a secret group, Black September, that carried out the assassination of Israeli, Arab, and American officials and the hijacking of European and American passenger planes. It took hostage and killed eleven Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics. It then seized ten Arab and Western diplomats at the Saudi Embassy in Khartoum, Sudan in March 1973, executing both the American Ambassador Cleo Noel and his deputy, Curtis Moore. The State Department concluded the operation had been “planned and carried out with the full knowledge and personal approval of Yasir Arafat.”

It took two decades of failed indirect talks between Israel and the PLO before they finally entered into face-to-face peace negotiations, resulting in the Norwegian-mediated Oslo Accords. They were made possible by a fundamental change in the policy of both toward the other.

On September 9, 1993, Arafat wrote a letter to then-Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in which the PLO formally recognized “the right of the state of Israel to exist in peace and security” and renounced the use of terrorism. Rabin, in return, replied that Israel recognized the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people and would begin negotiations with it. Four days later, Rabin and Arafat, the redeemed terrorist, shook hands in front of President Clinton at the White House in celebration of the Oslo Accords that established the Palestinian National Authority that rules today over parts of the Israeli-occupied West Bank.

Right now, in the heat of battle, it seems illusory. Still, there are several reasons to not give up hope.

Is it possible Hamas (the acronym for Islamic Resistance Movement) might take the same trajectory the PLO took thirty years ago, and Israel as well? Right now, in the heat of battle, it seems illusory. Still, there are several reasons to not give up hope.

Diplomatic pathway to reconstruction

First, Hamas, like Israel, badly needs to find a political strategy to deal with the “day after.” It cannot possibly cope on its own with the wasteland of destroyed buildings, homes, schools, hospitals, and roads that Gaza is today, and whose reconstruction is estimated to cost $40 to $50 billion. Secondly, it runs the risk of losing its current popularity among Palestinians if it cannot deliver the foreign aid Gaza will require to bring it back to life.

Already in 2017, Hamas, under economic and political pressure at home, began amending its description of an acceptable political settlement and moving toward de facto acceptance of a two-state solution. It announced that while it still sought Israel’s destruction, it would nonetheless accept as “an agreeable form” a Palestinian state based on its 1967 borders and Jerusalem as its capital as outlined in various UN and Arab resolutions.

The wealthy Gulf Arab monarchies, which the Biden administration and European Union are counting on to provide the bulk of reconstruction funds, will have enormous leverage over Hamas after the war. They are already telling Netanyahu they will not provide peacekeepers for Gaza unless he allows an independent Palestinian state. They can also let Hamas know they will not invest in Gaza’s reconstruction unless it recognizes Israel and renounces terrorism, just as the PLO did in 1993 to gain international recognition and financial and political support for the Palestinian National Authority.

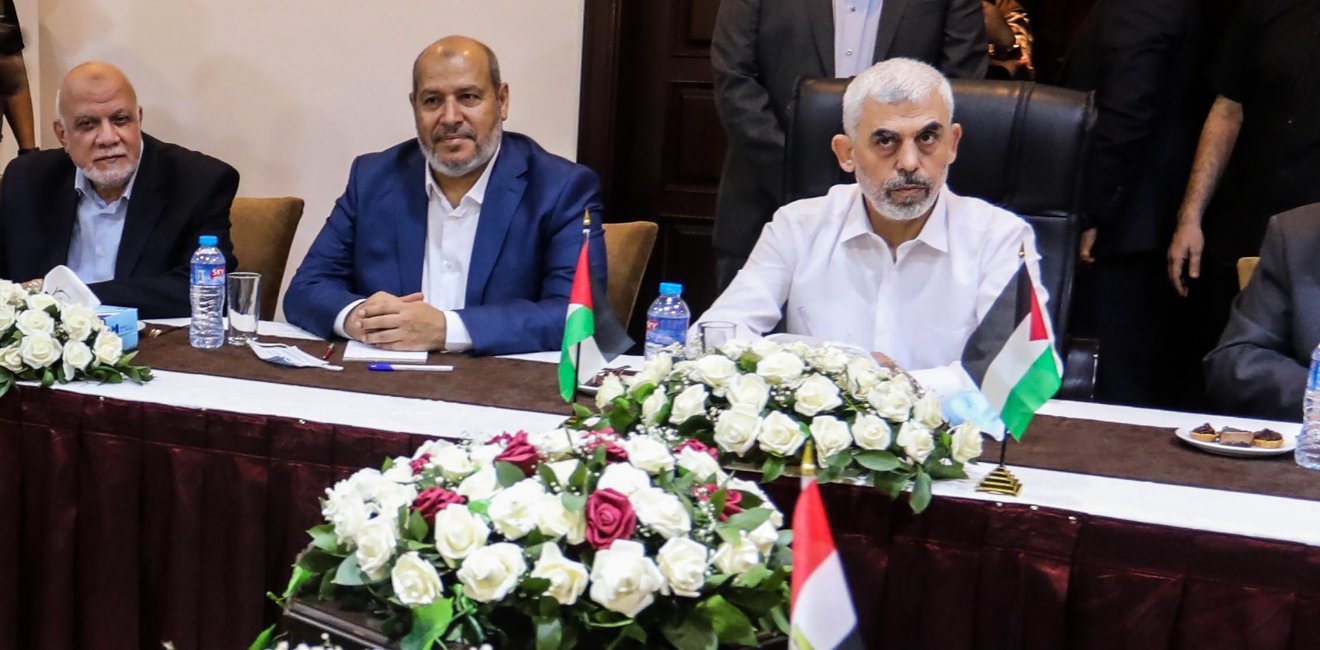

Qatar and Egypt have additional leverage over Hamas. Qatar, which has hosted Hamas political leadership at the request of the United States since 2012, could stop providing this refuge, and Egypt, neighboring Gaza and controlling the border crossing at Rafah, could squeeze Hamas’ only lifeline to an Arab country.

Nonetheless, it seems certain Hamas will have to switch from a mainly military to a political strategy.

To say the least, predicting the course of events the day after is difficult. Nonetheless, it seems certain Hamas will have to switch from a mainly military to a political strategy. Just as certain is the likelihood it will find itself under enormous pressure from Gaza’s destitute Palestinian population, rich Arab countries that recognize Israel, and an impatient international community to take the same road the PLO took thirty years ago.

Instead of pressing for the elimination of Hamas, the Biden administration should flex its own considerable diplomatic muscle with its Middle East friends to begin pressuring Hamas into doing just that.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not express the official position of the Wilson Center.