In the early hours of April 26, 1986, Reactor 4 at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant exploded, spewing tons of radioactive matter across Ukraine, Belarus, Russia and parts of Europe. The explosion released the radioactive equivalent of 100 Hiroshima bombs, and the nuclear fallout caused devastating economic, political, and social consequences for the region and beyond.

On April 26, 2006, the Woodrow Wilson Center's KENNAN INSTITUTE will host a full-day event to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Chernobyl. The panelists, some of whom are quoted below, will discuss the region's history, the accident's environmental impact and health effects, and consequences for the region and international community.

The Chernobyl disaster has been attributed to flawed reactor design, human error, and inattention to safety. On-site operators were shutting down the reactor to conduct a test but reduced power too quickly and destabilized the reactor. Operator errors during the test, including disabling safety mechanisms, contributed to its ultimate fate. Steam increased uncontrollably in the core, creating a rapid power surge that resulted in a series of fires and explosions. The fire burned for nine days, releasing eight tons of radioactive matter—including plutonium, uranium, cesium, and iodine—into the environment.

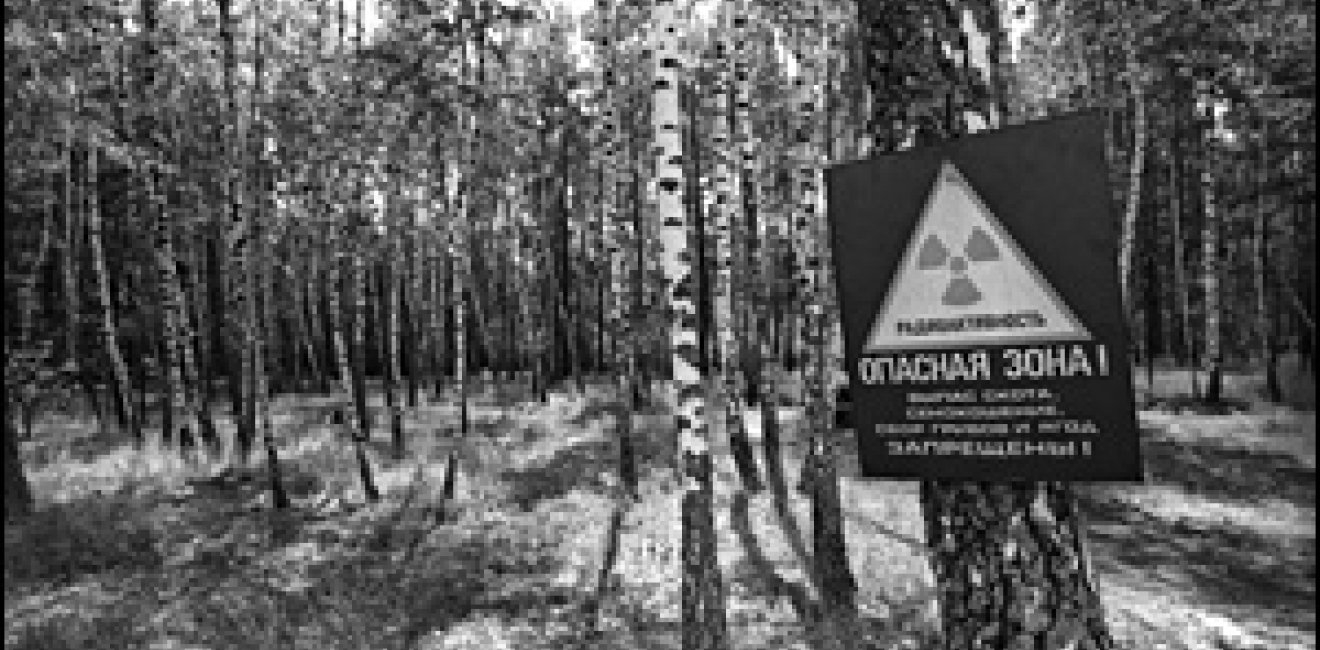

More than 100,000 people living within a 30-kilometer radius, now known as "the exclusion zone," were exposed to the radiation for days, if not weeks, before authorities evacuated them. In the coming years, an additional estimated 200,000 people were resettled. Currently, five million people live in parts of Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus that remain contaminated.

The enormity of this accident was unprecedented, but a pattern of safety and construction problems existed since the late 1970s when Chernobyl-type reactors first came on line. According to David Marples, a history professor at the University of Alberta, 29 emergency shutdowns occurred from 1977-1981, eight due to operator error, the rest due to technical problems. In 1978, more than 170 workers were injured in accidents throughout the Soviet Union and, that year, fires broke out in Chernobyl Reactor 3, then still under construction. In 1982, he said, another serious accident occurred at Chernobyl during a routine shutdown, contaminating soil and vegetation across some 20 square kilometers of land. News of this accident never reached the media.

Soviet officials knew the scope of the 1986 accident within days but concealed this news from the public and international media, as confirmed by newly declassified Soviet materials. "Politically, the Soviet Union was the main victim," Marples said. The Soviet leadership's mismanaged response to Chernobyl eroded the legitimacy of the Soviet system and contributed to its collapse.

Today, nuclear power remains a symbol of sovereignty for Ukraine, which otherwise depends heavily on Russian oil and gas imports. Ukraine closed the last of the functioning Chernobyl reactors in 2000, said Marples, but nuclear power still accounts for 45-50 percent of its electricity production. Rep. Marcy Kaptur, who co-chairs the Congressional Ukrainian Caucus and works on the issue of renewable fuels as a member of the House Appropriations Committee said, "I believe that Ukraine possesses the ability to power a new future for fuels that will cut the reliance on importaed petroleum and natural gas."

Ukraine is working to phase out the Chernobyl-type RBMK graphite reactor in favor of VVER water-pressurized reactors, which are considered somewhat safer. But, Marples said, these reactors still require proper containment, better-trained personnel, and improved safety mechanisms.

Then and Now

Though synonymous with the nuclear accident, Chernobyl—the city—once was a center of commerce and culture. Although mostly depopulated now, it had been a thriving center of Polish and Jewish culture, said Kate Brown, a historian who teaches at the University of Maryland at Baltimore County and whose book, A Biography of No Place, delves into the history of the region surrounding Chernobyl.

"The region went from a culturally and multilingual ethnic borderland to a homogeneous heartland," she said. The Soviet government deported Polish citizens from the region in 1936 and the Nazis exterminated the Jews who had lived there during the war.

"Chernobyl has become an icon of the suffering of the Ukrainian people at the hands of the Soviet state," said Brown. "Yet the accident also serves as a requiem for six decades of mass dislocation of non-Ukrainians from the region."

Today, Chernobyl has become one of Europe's largest wildlife habitats, said Mary Mycio, a media law adviser at the International Research and Exchanges Board based in Kyiv and author of The Wormwood Forest: A Natural History of Chernobyl. During numerous visits to the area, she observed large animals such as moose, wild boar, wolves, horses, and deer as well as rare species of birds.

"When we arrived, dozens of black storks pierced the air above. Thousands of ducks took off in a tornado-like cloud along with mute swans, grey herons, and white egrets that flew deep into the wetlands," she said. "In the absence of humans, Chernobyl's wildlife is flourishing, beautiful and radioactive."

But the land yielded little before the accident. "People picked berries, grew a little rye, hunted and fished," Brown said. "The Soviets put the plant there in an attempt at economic revitalization, to put Chernobyl on the map in the 20th century." And they did just that.

The Health Debate

The health effects from Chernobyl are the center of intense debate. In September 2005, the Chernobyl Forum—an initiative of the International Atomic Energy Agency in conjunction with other UN agencies and the governments of Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus—released a controversial report stating that a total of 4,000 people died or could die from radiation-related illnesses, including 50 emergency workers who already died, and nine children who died from thyroid cancer. This total, the report claims, comes from a sample of 200,000 emergency and recovery workers in the year following the accident, 116,000 evacuees, and 270,000 residents of the most contaminated areas. Further, the report cites no evidence of decreased fertility or increased adverse pregnancy effects due to radiation exposure, but did cite a marked increase in anxiety-related illnesses.

"The Chernobyl Forum report confirms what scientists have been saying for years, that the health and environmental effects were more mild than expected," Louisa Vinton, a senior program manager and head of Chernobyl coordination at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), told Centerpoint. Children contracted thyroid cancer by ingesting radioactive iodine from cow's milk, she said, but most of them survived and all who would contract the disease in this manner already have been exposed. "The health impact has passed."

"I think the numbers are debatable," argued demographer Murray Feshbach, a senior scholar at the Wilson Center. "It will be a long time before we can see the full effect." While iodine may decay quickly, he said, it could take upwards of 25 years for thyroid cancer to develop. Plutonium, for example, can remain in the lungs, bloodstream, liver, and skeletal tissue for many years, causing damage that may later develop into cancer.

Ukrainian authorities estimate thousands of deaths occurred from radiation exposure and a Russian-American medical survey found more than 10,000 people were badly irradiated, said Feshbach. He refuted the Chernobyl Forum's sample set, saying their statistics exclude thousands of recovery workers from other parts of the region. Some estimate 600,000 or more recovery workers were involved in cleanup beyond first-year efforts.

Feshbach also distinguished between mortality and morbidity rates, contending many people are living with defects and diseases that require lifelong treatment and medication. In addition, the Children of Chernobyl Relief Fund reported that an Israeli-Ukrainian study found children born to emergency workers, known as "liquidators," experienced a seven-fold increase in chromosome damage compared with their siblings born before the accident. Other studies cite rare birth defects, including malformed organs and deformed limbs, as documented in the film, Chernobyl Heart.

"Documentaries such as Chernobyl Heart distort the truth," said Vinton. "They show [deformities] in affected and unaffected areas in Belarus. Their facts are not supported, and these diseases are not necessarily due to radiation."

Unhealthy lifestyles and poor health care in former Soviet countries increase the overall risk of disease, said Vinton, which makes it difficult to determine the source of certain illnesses. The lack of public, reliable health data prior to 1986 further hinders comparative analysis.

Remembering

The Kennan Institute's day of commemoration, on April 26, will conclude with a viewing of the documentary Chernobyl Heart, followed by a discussion led by the filmmaker. The next day, a Congressional briefing will examine the accident's continuing effects on human health and agriculture; securing the sarcophagus and radioactive waste in the exclusion zone; U.S. government and international assistance, and economic development in the affected regions. The program also will feature a photo exhibit on Chernobyl. Rep. Kaptur said, "Our hope is that this photo exhibit will illuminate the human stories behind the Chernobyl catastrophe."

Related Links