The H-2A program allows farm employers to request certification from the US Department of Labor to recruit and employ foreign workers to fill seasonal farm jobs, generally defined as those lasting up to 10 months. DOL certified 257,666 jobs to be filled with H-2A workers in FY19, when the top five H-2A states, Florida, Georgia, Washington, California, and North Carolina, accounted for over half of all H-2A jobs certified.

The US Department of State issued almost 205,000 H-2A visas in FY19. Mexicans received over 90 percent of H-2A visas, followed by almost three percent for Jamaicans and two percent for Guatemalans.

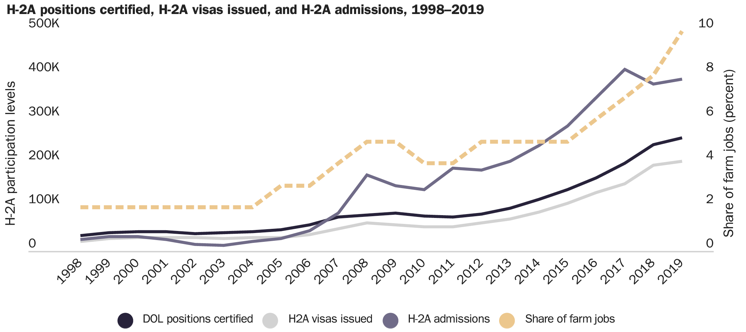

The H-2A program was expected to expand in the 1990s after the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 imposed federal sanctions on employers who knowingly hired unauthorized workers. Instead, the H-2A program shrank as the Florida sugarcane harvest was mechanized and unauthorized Mexicans arrived in large numbers and presented false documents that satisfied IRCA’s I-9 right-to-work documentation requirements.

The number of US farm jobs certified to be filled with H-2A workers remained below 100,000 until 2014, doubled to over 200,000 in 2017, and has continued to increase. There are about a million year-round equivalent jobs in US crop agriculture, where most H-2A workers are employed. H-2A workers are in the US an average six months, so they fill 10 percent of the year-round equivalent jobs in US crop agriculture.

California has about 400,000 year-round equivalent jobs in crop agriculture. The 12,000 full-time equivalent H-2A workers filled about three percent of the state’s crop jobs in 2019. The top 10 H-2A employers in California accounted for over three-fourths of the 23,000 H-2A jobs certified in FY19, led by Fresh Harvest with almost 5,000 jobs certified.

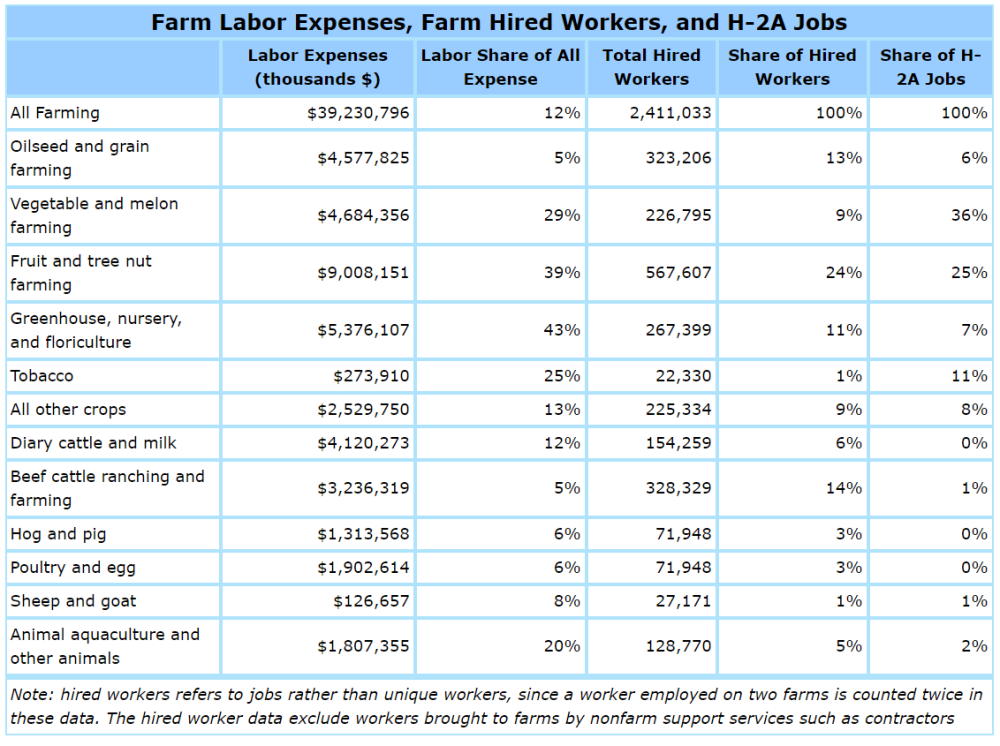

Half of the $39 billion in US farm labor expenses reported by farmers to the Census of Agriculture in 2017 was paid by farms producing fruits, vegetables and horticultural specialties, FVH commodities. Labor was 30 to 40 percent of FVH farms’ production expenses, and FVH farms accounted for two-thirds of all H-2A jobs certified.

In March 2020, DOS began to grant visas to H-2A workers without the in-person interviews that are normally required. Two-thirds of H-2A visas are issued in Monterrey, Mexico, where US consular officers issue up to 2,000 H-2A visas a day.

H-2A workers travel to Monterrey, complete application forms and are fingerprinted and photographed, after which their DS-160 visa applications and biometric information is taken to the US consulate for processing. Workers must normally be available for in-person interviews, although many returning H-2A workers are not interviewed.

Hernández-León (2020) emphasizes the key role of the recruiters who select workers and arrange for them to travel to Monterrey. Some recruiters use Facebook to find workers, and some prefer “new” to experienced H-2A workers who may be more cautious and careful about signing contracts.

Recruiters take migrants to DOS-approved document processors in Monterrey, often women who know how to complete US visa applications efficiently, including some who were previously local hires at the US consulate. Recruiters and document processors arrange housing for H-2A workers in Monterrey hotels while the US consulates process the paperwork, which reportedly allows some of the drivers and clerks with whom H-2A applicants interact to extract fees from them.

Both recruiters and document processors coach H-2A applicants to say as little as possible during in-person interviews with US consular officials. Over 90 percent of applicants are approved and, after H-2A visas are stamped in worker passports, workers travel by bus or van to their US workplace. US employers are responsible for all worker-incurred costs, including the $190 cost of the H-2A visa and transportation and food en route to the US workplace. However, employers do not have to reimburse H-2A workers for their expenses until halfway through their contracts.

There is widespread agreement that the recruitment of H-2A workers in Mexico is a “dirty business.” Experienced H-2A workers sometimes charge friends and relatives to introduce them to recruiters who can offer them H-2A contracts. Similarly, some recruiters charge for jobs, and some US employers try to recoup what they paid to Mexican recruiters from H-2A workers after their arrival in the US. Recruiters seek to satisfy US employers, so they blacklist particular workers at the request of employers.

Article 28 of Mexico’s 1970 labor law, revised in 2019, requires that H-2A and other contracts for work abroad to be registered with the Mexican Ministry of Labor. Article 28 explicitly states that employers pay all worker costs, including for recruitment, visa fees, and food and transportation. Mexico had 433 registered labor recruiters in 2019, including nine registered to recruit workers for foreign jobs. Mexico’s MOL conducted 81 inspections of recruiters between 2009 and 2019, and found no violations of Article 28

CDM (2020) surveyed 100 Mexicans who worked in the US with H-2A visas after they returned to Mexico and found that all had experienced at least one “serious” violation of their labor rights, while 94 percent experienced three or more violations.

CDM did not report violations by stage of the H-2A process, viz, recruitment in Mexico, transportation to the US consulate and then to the US workplace, employment and housing in the US, and worker returns to Mexico. CDM emphasized that many workers paid fees in Mexico to obtain H-2A job offers. Speakers of indigenous languages were more likely to report paying recruitment fees and to experience worse conditions in the US than Spanish-only speakers.

Some of the violations reported to CDM are objective, such as below-contract wages. Others are subjective, such as workers who reported feeling unable to quit their jobs. CDM did not distinguish between first-time and repeat H-2A workers, but World Bank worker-cost surveys suggest that returning guest workers are more knowledgeable and experience fewer violations.

Bier, David. 2020. H?2A Visas for Agriculture. Cato.

DOL certified almost 258,000 jobs to be filled by H-2A workers in FY19, and DOS issued almost 205,000 H-2A visas

Mexicans receive over 90 percent of the H-2A visas issued

Jamaicans were not required to have H-2A visas until 2016

The number of farm jobs certified to be filled by H-2A workers doubled between FY14 and FY17

Note—DHS admissions data count each admission of an H-2A holder, so that each entry of an H-2A worker who elects to live in Mexico and commute daily to US farm jobs is counted. Admissions are NOT a count of unique workers

Half of the $39 billion in US farm labor expenses in 2017 was on the FVH farms that accounted for two-thirds of H-2A jobs certified

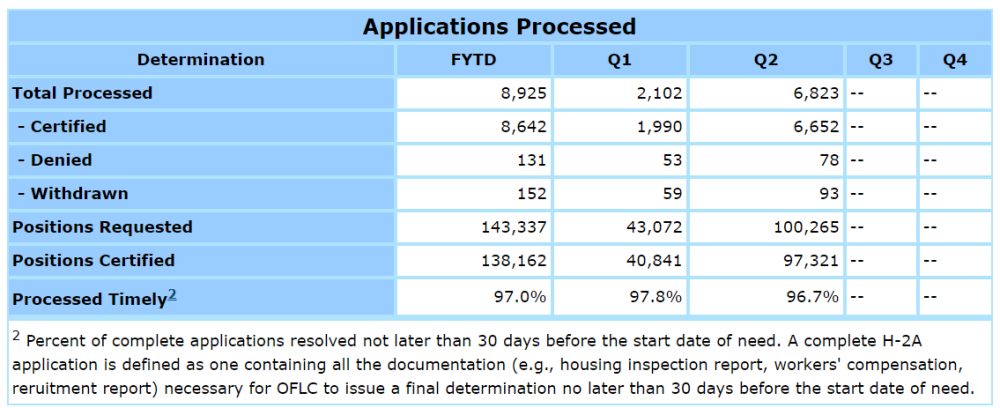

DOL received over 13,000 employer applications and certified 258,000 jobs to be filled with H-2A workers in FY19

DOL received almost 9,700 employer applications and certified 138,000 jobs to be filled with H-2A workers in the first half of FY20, up 12 percent from the first two quarters of FY19

Author

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more