If you ask your average Finn what their country is best known for, they might point to saunas or their regular top ranking as the world’s happiest country. But for Finland, a country in which almost every port freezes over with ice up to 30 inches thick for up to half of the year–and 92.4% of trade in 2022 flowing through these ice-prone ports each year–it has had to develop a specialized knowledge of icebreakers and icebreaking technology. Finland leads the world in icebreaker design and construction, with an often-cited fact that 80% of the world’s icebreakers are designed by Finnish firms and more than 60% of icebreakers are built in Finnish shipyards. This hard-earned knowledge has made Finland a global authority in the icebreaker industry and it now seeks to share its know-how via the ICE Pact–a trilateral partnership between the United States, Canada, and Finland. Before turning to the larger implications of the trilateral partnership, it is worth unpacking what allows Finland to be a giant in the icebreaker industry, evaluate its current icebreaker fleet and its capabilities, as well as look ahead to its icebreaking industry’s potential growth under ICE Pact.

Finland’s Unique Maritime Industry

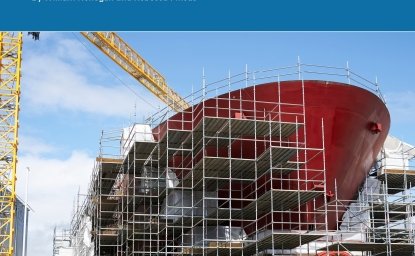

Finland’s shipyards have the capacity to produce icebreakers quickly and at a reasonable cost. It is estimated that, compared to US icebreaker production underway, the average Finnish icebreaker would cost about a fifth of the price and be completed in about 24 months after a contract is signed, in part due to the ecosystem developed around the shipyards and close coordination with the Finnish government. The Finnish Marine Industries (Meriteollisuus in Finnish) as an industry group represents the combined industries of Finland’s maritime cluster that makes Finnish shipbuilding so cost effective and efficient. Finland’s maritime industry consists of over 1,100 companies and employs more than 25,000 people. The ecosystem surrounding the major Finnish shipyards is the secret sauce that makes their maritime industry one of the most competitive in the world.

Finland’s shipyards have the capacity to produce icebreakers quickly and at a reasonable cost. It is estimated that, compared to US icebreaker production underway, the average Finnish icebreaker would cost about a fifth of the price and be completed in about 24 months after a contract is signed, in part due to the ecosystem developed around the shipyards and close coordination with the Finnish government.

Many European shipyards have ceased operations or significantly declined in output, in favor of cheaper labor at shipyards in Asia. Today, China, Japan, and South Korea make up more than 90% of shipbuilding worldwide. The shipbuilding expertise preserved in Finland is therefore highly specialized, building ice resistant vessels, ferries, and other specific functions. Beyond breaking up ice in Finland’s ports and allowing the flow of goods, its icebreaker fleet also plays a vital role in search and rescue, oil spills, route planning, emergency towing, and maritime traffic control. Finland’s icebreakers are operated by a state-owned enterprise, compared to the United States or Canada where the country’s navy or coast guard operates their icebreakers.

In the past, Russian ownership, support of, and business for Finnish shipyards has raised concerns in US-Finnish relations. However there was a hard break in relations between Russia and Finland with the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Since then, all ongoing projects with Russian companies have ceased, the main land border with Russia has been closed since November 2023 following waves of instrumentalized migration, and Finland’s decision to join NATO cemented the Nordic nation’s place in Western security architecture. Although it was never in doubt that Finland aligned itself with the West–its purchase of 64 US-made F-35 fighter jets in 2021 sent a clear signal to Washington–Finland’s decision to join NATO removed the final inkling of doubt and paved the way for increased icebreaker cooperation between the US and Finland. Finland’s President, Alexander Stubb, said that the ICE Pact would not be possible without Finland’s NATO membership. With this concern removed, Finland can raise NATO’s icebreaking capabilities through its knowledge and shipyards.

There are three major shipyards in Finland: Helsinki shipyards, Turku shipyards, and the Rauma shipyard.

- Helsinki shipyards were established in 1865 and began building icebreakers in 1910. As of November 2023, Davie (a Canadian company) is the largest owner of the Helsinki shipyard, taking over after the previous Russian owners were ousted following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. In 2010, Russian ownership was initially 50 percent through the United Shipbuilding Corporation, in partnership with a South Korean company, STX. Beginning in 2017, the Russian company sought to sell its holdings after increased US sanctions against the company limited business.

- Meyer Turku operates out of the Turku shipyards which have been in operation since 1737. The Turku shipyards, located in the former capital of Finland on the southwest coast, prides itself in constructing modern and environmentally friendly vessels, especially cruise ships and specialized vessels. Turku shipyards produced the Icon of the Seas, the world’s largest cruise ship in the world that entered into service in 2024. The Turku shipyard is so large that more than half of the companies involved in the Finnish maritime cluster trade with it.

- The Rauma shipyard is run by Rauma Marine Constructions (RMC), a company founded in 2014, on Finland’s west coast. After STX withdrew from Rauma in 2013, the shipyard was almost shut down, nearly ending 300 years of production and potentially costing 600 jobs from Rauma and another 100 from Turku, before RMC was launched. In Rauma, three icebreakers have been designed and built between 1993 and 1998: the Fennica, Nordica, and Botnica. The Fennica and Nordica are still in operation by Arctia Oy, while the Botnica was sold to the Port of Tallinn in 2012. RMC is still engaged in the maintenance of the Nordica and Fennica, and a project to upgrade the capabilities of the icebreaker Otso was completed in 2015. The four multi-role corvettes commissioned by the Finnish Navy are also being designed in Rauma and will have the ability to operate under icy conditions.

Once an icebreaker launches from the major shipyards, how is it operated and by whom? The majority of Finland’s icebreaker fleet is operated and managed by Arctia Ltd, a company fully owned by the Finnish state and its corporate governance falls under the Ministry of Transport and Communications. Arctia is operated by 423 staff (as of 2023), of which about 254 are marine personnel.

Beyond government ownership of the company managing the icebreakers in operation, the Finnish government also has considerable investments in major companies in the value chain of the icebreaking design and construction process. Two thirds of Aker Arctic, a private company, are owned by the Finnish government, making it an autonomous corporation in practice but which wishes to remain in good standing with its largest stakeholder, the government. The Finnish government stepped in to prevent foreign ownership after the previous South Korean owners, STX, divested from the company. As a company, Aker Arctic specializes in the development, design, engineering, consulting, and testing of ice-going vessels, including icebreakers. Among its portfolio of icebreaker designs is the Polaris (Finland’s newest icebreaker) and the USCGC Mackinaw, a heavy icebreaker operated by the United States Coast Guard in the Great Lakes.

Beyond government ownership of the company managing the icebreakers in operation, the Finnish government also has considerable investments in major companies in the value chain of the icebreaking design and construction process.

Finland’s Current Icebreaker Fleet

Pinning down exactly how many ships make up Finland’s icebreaker fleet is difficult, in part due to various classifications of hull thickness and icebreaking capabilities. The US Coast Guard lists in a 2020 infographic that Finland has 11 icebreakers (two of which have since wound up in Russia, another is a tugboat with limited icebreaking capabilities). The number is in constant flux as ships undergo repairs or are refitted.

According to Finland’s maritime strategy, at least nine icebreakers are needed in normal or moderate winter conditions to ensure the safe usage of its ports year-round. At the time of publication, Finland’s icebreaker fleet consists primarily of 8 vessels (the Polaris, Fennica, Nordica, Otso, Kontio, Urho, Sisu, and Voima). An additional 6 vessels have icebreaking capabilities and, although they are not primarily used as such, could be utilized in a state of emergency (the Louhi, Ahto, Zeus of Finland, Turva, Sampo, and Calypso/Saimaa).

At the time of publication, Finland’s icebreaker fleet consists primarily of 8 vessels (the Polaris, Fennica, Nordica, Otso, Kontio, Urho, Sisu, and Voima). An additional 6 vessels have icebreaking capabilities and, although they are not primarily used as such, could be utilized in a state of emergency (the Louhi, Ahto, Zeus of Finland, Turva, Sampo, and Calypso/Saimaa).

The pride and joy of Finland’s icebreaker fleet is its newest vessel, the Polaris. Launched in 2017, the year Finland celebrated its 100th anniversary of independence, the Polaris is a cutting edge icebreaker powered by liquified natural gas (LNG). Russian icebreakers famously rely on nuclear power for their fleet, but as of 2021 they too are experimenting with designing a LNG-powered icebreaker. The Polaris has a planned 50 year lifecycle and is operated by a 16-member crew. As the first LNG-powered icebreaker, the Polaris is a next generation heavy icebreaker and will likely be a model for future vessels built as part of ICE Pact.

The MSV Fennica and Nordica are sister ships, designed in Rauma and launched in 1993 and 1994, respectively. Both are considered multipurpose icebreakers, balancing power with precision to adapt to many operating environments. The two Otso (referring to a Finnish mythological bear) class vessels: the IB Otso and Kontio are identical ships that launched in 1986 and 1987, respectively. The Otso and Kontio replaced the aging Karhu (bear in Finnish) class icebreakers (the Karhu, Murtaja and Sampo) and are typically the first to be deployed in the icebreaking season. They are less powerful than the larger Urho and Sisu, and were built with cost efficiency in mind, reducing operating costs with a smaller crew and an efficient hull design. The Kontio was outfitted in 2010 with oil recovery equipment, making it one of the go-to ships in the event of a major oil spill.

The veteran vessels of the Finnish icebreaking fleet are the two Urho class ships–the IB Urho and Sisu–and the “old faithful” IB Voima, the latter of which helped launch Finland’s icebreaking industry into the public eye. The Urho–named after President of Finland Urho Kekkonen–launched in 1975, followed shortly thereafter by her sister ship the Sisu in 1976. The Urho and Sisu have three additional sister ships flagged by Sweden that were developed in cooperation with the Swedish government, the Atle (1974), Frej (1975), and Ymer (1977). The Urho class vessels are workhorses capable of displacing 60% more ice than its predecessor (at the trade-off of less ice resistance). For the first time in history, all 23 of Finland’s ports were fully ice-free thanks to the Urho and Sisu. The Sisu was named after the untranslatable Finnish word that defines the country’s stoic tenacity, but its name also commemorates Finland’s first diesel-electric icebreaker that launched in 1939, also named Sisu. It was replaced in 1976 by the much more powerful Sisu still in operation today, the original Sisu was briefly renamed the Louhi from 1975 to 1986 before being broken up.

The IB Voima, the oldest icebreaker still in operation in Finland, was commissioned in 1954 and celebrated its 70th anniversary in February 2024. The Voima was built by Wärtsilä (whose engine designs power most of Finnish icebreakers) as part of Finland’s post-war rebuilding program. War reparations to the Soviet Union, amounting to $300 million in ships and machinery, led to the design and creation of what was then considered to be the most technically advanced icebreaker in the world. The Voima has four sister ships, three were given to the Soviet Union (Kapitan Belousov in 1954, Kapitan Voronin in 1955, and Kapitan Melehov in 1956), and one was delivered to Sweden (Oden in 1957). It received a major upgrade between 1978 and 1979 to modernize its machinery, including a completely new main engine, new quarters for the crew, and a new bridge. Because the renovation took place around the same time as the launch of the Urho class vessels, it shares many technical capabilities and similarities to the Urho and Sisu. Although much of its interior has been replaced, the Voima remains one of the oldest icebreakers in active service. In 2016, the Voima received a ten-year life cycle extension and in 2023 received a major update of its main drive and diesel automation.

The aforementioned eight icebreakers are all operated by Arctia and are state-owned. There are a handful of additional icebreakers in operation that, in the event of a major crisis or incident, could be called upon for service. The Finnish Navy operates a pollution control vessel named Louhi, with pennant number 999 on her hull. The Louhi entered service in 2011 and was designed by Työvene (Työvene also designed the Harbour Icebreaker IB Ahto, operated by Arctia). It is formally owned by the Finnish Environment Institute (SYKE) but operated by the Finnish Navy. Although the Louhi’s main mission is not solely icebreaking, it has the hull strength and capacity to operate as an icebreaker if necessary.

Alfons Håkans, based in Turku, designs tug boats capable of operating in icy conditions. Its considerable fleet consists of 39 tugs, 13 barges, and 16 work boats. Of its 39 tugs, 8 are classified as 1A Super and 22 vessels as 1A, meaning they can operate in icy conditions and help to ensure vessels can deliver goods to ports across Finland and the Baltics. The Zeus of Finland is the best known and one of the most capable icebreaking tugs operated by Alfons Håkans. There exists various ice classes rankings across the world, with the most standardized being the Polar class, however Finland operates using the Finnish-Swedish ice class. This consists of rankings from 1A Super, 1A, 1B, and 1C. There has been a proposition for a new class, the 1A Super+, to separate those vessels which are able to operate without assistance practically in any conditions.

Additionally, the Finnish Border Guard vessel Turva, launched in 2013, is capable of breaking ice up to 80 centimeters (31 in) in thickness and is sometimes counted towards Finland’s icebreaking fleet. The Turva is the largest vessel in the Finnish Border Guard’s fleet and is its first to be powered by LNG. The Sampo icebreaker, which entered into service in 1960, was bought by the northern town of Kemi, Finland as a tourist attraction in 1987. The City of Kemi began operating the Sampo icebreaker in 1988 and it has become a major tourist draw to the region.

Another icebreaker that is occasionally included in some lists of Finnish icebreakers is the Calypso/Saimaa, operated by Alfons Håkans. The tugboat Calypso has an attachable, self-propelled icebreaking bow (the first of its kind) that allows it to assist vessels on Finland’s largest Lake Saimaa. Lake Saimaa, the fourth largest freshwater lake in Europe, is connected to the Gulf of Finland via a canal near Vyborg, Russia. Prior to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Saimaa Canal was regularly used by Finnish recreational vessels seeking to drydock for the winter. Half of the canal is in Finnish and half in Russian territory, with a 1962 lease agreement renewed in 2012 regulating use of the waterway. Despite the canal formally reopening for cargo and passenger boats in June 2024, virtually no traffic has been reported. The extremist Task Force Rusich paramilitary organization has claimed to have been patrolling the Russian side, prompting concerns over the security of canal maintenance employees. Task Force Rusich is sanctioned by the United States’ Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) and described them as “a neo-Nazi paramilitary group that has participated in combat alongside Russia’s military in Ukraine.” Effectively, this means that the Calypso is locked in Lake Saimaa, unable to traverse the Saimaa Canal to the larger Gulf of Finland and Baltic Sea if needed in an emergency. It could be transported by road or rail, if necessary. In the same vein as the US Great Lakes, Lake Saimaa needs an icebreaker onhand.

Finland’s Lost Icebreaker: The Thetis

Finland has a long history of building and selling icebreakers to the former Soviet Union and Russia (such as the Karhu, Apu, or more recently the Hermes), its neighbors in the Baltics (such as the Botnica and Tarmo, which were sold to Estonia, and the Varma, which was sold to Latvia), and for its fellow Nordics (primarily Sweden, Norway’s ports remain largely ice free due to the Gulf Stream). Finnish shipyards continued to produce ships for Russia and Russian companies until the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Although there was a hard break in sales to Russia following the 2022 invasion, a Finnish icebreaker still wound up under Russian ownership in 2023: the Thetis. In operation by Alfons Håkans until July 2023, the Thetis was sold to a Hong Kong-based company that transported the icebreaker to Istanbul. The ship was later re-routed to St. Petersburg for repairs, with the new owner claiming the port at Istanbul was unable to accommodate the ship. Now, the Thetis is based out of Murmansk and flies a Russian flag. Alfons Håkans did not violate international sanctions on Russia and conducted a thorough investigation of the buyer, who reportedly had neither links to China nor Russia. This underreported saga demonstrates: 1) the geopolitical importance of icebreakers, 2) continued attempts by Russia to coercively acquire Western technology, and 3) the important role of friendshoring and limiting access to next generation icebreaking technology amongst allies.

Finnish Icebreakers: A Rare Export

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and severing of economic ties with Russia, Finland has been in search of a market for its exceptional maritime and shipbuilding base. The ecosystem surrounding Finnish icebreakers allows them to be built at a remarkable speed, at a price point far lower than anyone else, and their technical expertise mean Finnish icebreakers are cutting edge. Finland’s current fleet of icebreakers meets domestic demand to keep their ports operational year-round, but as the Voima’s age and continued extensions shows, Finland too needs new icebreakers. Now, as a NATO ally, Finland can usher in a new era of icebreakers by sharing its know-how with the alliance and help to minimize the advantage Russia has in icebreaking capabilities.

Authors

Global Europe Program

The Global Europe Program is focused on Europe’s capabilities, and how it engages on critical global issues. We investigate European approaches to critical global issues. We examine Europe’s relations with Russia and Eurasia, China and the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa. Our initiatives include “Ukraine in Europe”—an examination of what it will take to make Ukraine’s European future a reality. But we also examine the role of NATO, the European Union and the OSCE, Europe’s energy security, transatlantic trade disputes, and challenges to democracy. The Global Europe Program’s staff, scholars-in-residence, and Global Fellows participate in seminars, policy study groups, and international conferences to provide analytical recommendations to policy makers and the media. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

US, Canada, and Finland Unite to Build Advanced Arctic Icebreakers

Navigating the Arctic: The Ice Pact and the Future of Icebreakers