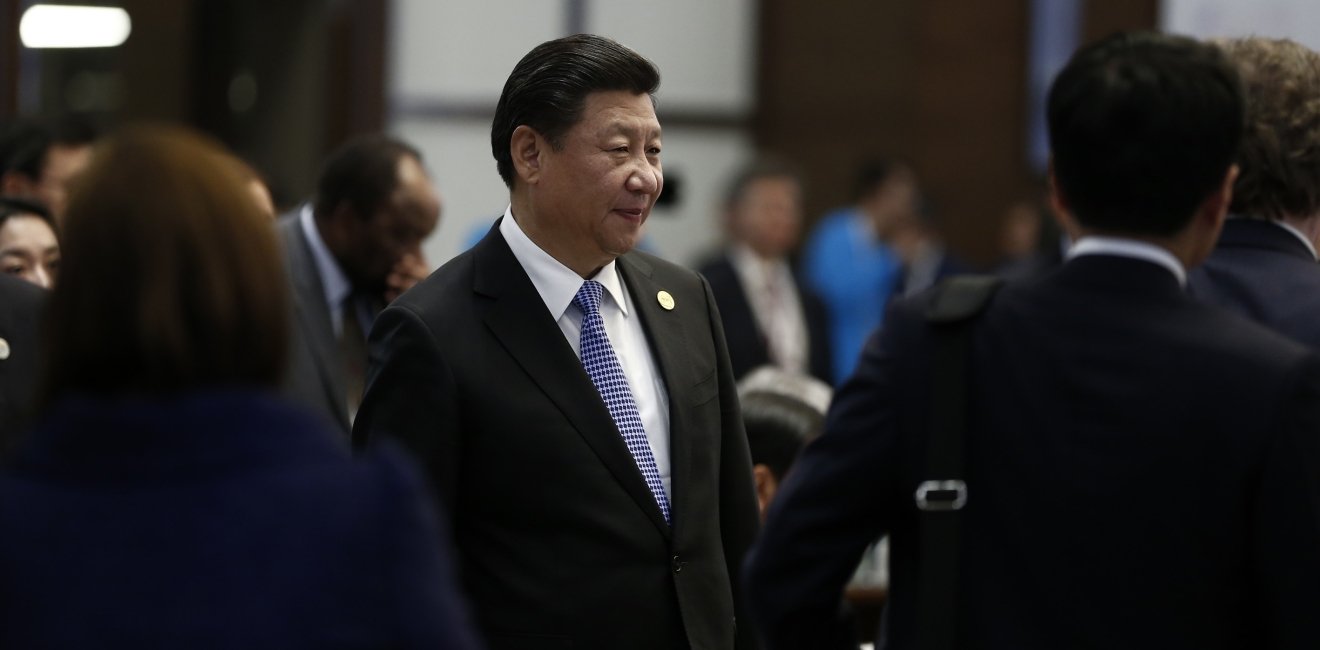

The Paris attacks have been met in China with an outpouring of sympathy from the populace and a statement of support from Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping. China’s concern is genuine. Many urban Chinese are committed internationalists and approximately 2.5 million of them visit France as tourists each year. Although France is one of the guilty imperialist parties in Beijing’s “Century of Humiliation” narrative, it is also the nation in which Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping studied in their youths and to which China sent over 100,000 laborers, the corps de travailleurs chinois, at the end of World War I. China feels both historic and contemporary ties to France and is truly horrified by the violence of November 13.

Chinese have been quick to ask, however, why terrorism in China does not elicit the same global empathy that France is now receiving. When a group of Uighurs slaughtered Chinese civilians in the Kunming train station in 2014, the international press moved quickly from brief expressions of shock to in-depth reporting on the brutal treatment that Uighurs receive in Xinjiang. In the eyes of many Chinese, what should have been a story about China’s victimhood became yet another story about China’s alleged bullying. As tributes to the victims of Paris pour in, the disparate treatment of tragedies in China and Europe reveal to the Chinese, once again, that the West operates by self-serving double standards.

China’s sense that its own terrorism problems are shrugged off by the international community conditions its responses to Paris. The grief of China’s netizens is tempered by criticism of France’s prejudicial treatment of Middle Eastern migrants and its history of imperialism in North Africa. American policies in Syria and Libya are also depicted as causes of the attacks. A cursory survey of Chinese Internet postings indicates that most of these critiques reflect sober opinion and are not nationalist rants.

Against this background, we should not expect China’s genuine sympathy to result in policy changes any time soon. China still does not see itself as having a direct stake in such distant issues. In the Middle East, as in Ukraine, furthermore, China is striving to uphold core diplomatic principles on either side of the divide. In Ukraine, China’s fear of color revolutions and its abhorrence of outside agitators incline it toward sympathy with Moscow. But its bedrock belief in the inviolability of sovereign territory, its opposition to interference in the internal affairs of other nations, and its advocacy of peaceful solutions limit its support for the Russian cause. China’s view of Ukraine is inconsistent but, with no major stake in the outcome, China is free to stand on the sidelines and profess principles without incurring costs.

Regarding Paris, China is adamant in its condemnation of terrorism but it will not support a prolonged French or American campaign against the Islamic State. Because it is not directly threatened by the Islamic State, China will remain on the sidelines, reminding all concerned that peace is better than war and goodness is better than badness. China’s recitation of high ideals is not aimed at solving international conflicts; its primary goal is to build support for the Beijing government within China by reminding citizens that the People’s Republic practices a moral foreign policy. Even the many Chinese who are critical of the Communist Party’s domestic performance are proud of their nation’s supposed rectitude in international affairs and are confident that, as China’s power grows, China will not become an American-style superpower. Such behavior is inconceivable because, as Xi Jinping puts it, “invading others and seeking global hegemony is not in the genes of the Chinese nation.”

But the Chinese nation is changing. With his Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and One Belt, One Road initiative, Xi is positioning China as the leading architect of Eurasian integration. As China’s investments grow, so will its involvement in political quagmires that make it impossible to gloss over conflicts in its core foreign policy principles. China cannot defend its expanding global interests unless it becomes more active in the Middle East, in Europe, and nearly everywhere else. A more active foreign policy will require China to accept—or, more likely, to rationalize—its own double standards and interference in others’ internal affairs.

In its response to the Paris attacks, the Chinese Communist Party builds domestic support for its foreign policy while incurring no costs. There is nothing noble in this posture, but there is nothing odious in it, either. China is simply playing the cards it holds. And if we are annoyed by China sermonizing from the sidelines, we must ask whether we would be even more put out if China actually took to the field.

The opinions expressed here are solely those of the author.