Q: Describe your background and what brought you to the Wilson Center.

I am an associate professor in the History Department at the University of Arizona. My research and teaching focus is on medieval European and early world history, particularly the histories of games and foods in early societies. This is actually my second stint at the Wilson Center, but my first at the Kennan Institute. In the fall of 2009 I received an East European Studies Research Scholar Grant as part of the Global Europe Program. At that time I was working on my first book, ‘The Slippery Memory of Men’: The Place of Pomerania in the Medieval Kingdom of Poland (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2013). This book analyzes a series of medieval conflicts between the Teutonic Knights and Polish rulers at the same site as twentieth-century conflicts between Germans and Poles—the Polish Corridor and Free City of Danzig. My time at the Wilson Center in 2009 was one of the best experiences of my professional life, and it is an honor to be back. My research in the past decade has expanded both chronologically from the Middle Ages into modern history and geographically from Europe into Russia and Eurasia, which brought me to the Kennan Institute.

Q: What project are you working on at the Center?

The project I am working on at the Center is “Where East Meets North: Medieval and Early Modern Perceptions of Eastern Europe and Eurasia.” It analyzes how medieval and early modern Europeans in both western and eastern Europe—encyclopedists, chroniclers, map makers, and travelers (both real and imagined)—invented a nearer near east for Europe, a geographical part of Europe which supposedly had more in common with Asia than with Europe. I just published an article related to this larger project “”Und gras vor spise zeren’: Migration, Fermentation, and the Map of Civilization in the Baltic Crusades,” in Authorship, Worldview, and Identity in Medieval Europe, ed. Christian Raffensperger (New York: Routledge, forthcoming). It explores the invention of medieval eastern European foodways by analyzing an anecdote from a papal letter asking whether a Polish duke was seriously not going on crusade in the Mediterranean because he could not drink his native beer and mead there.

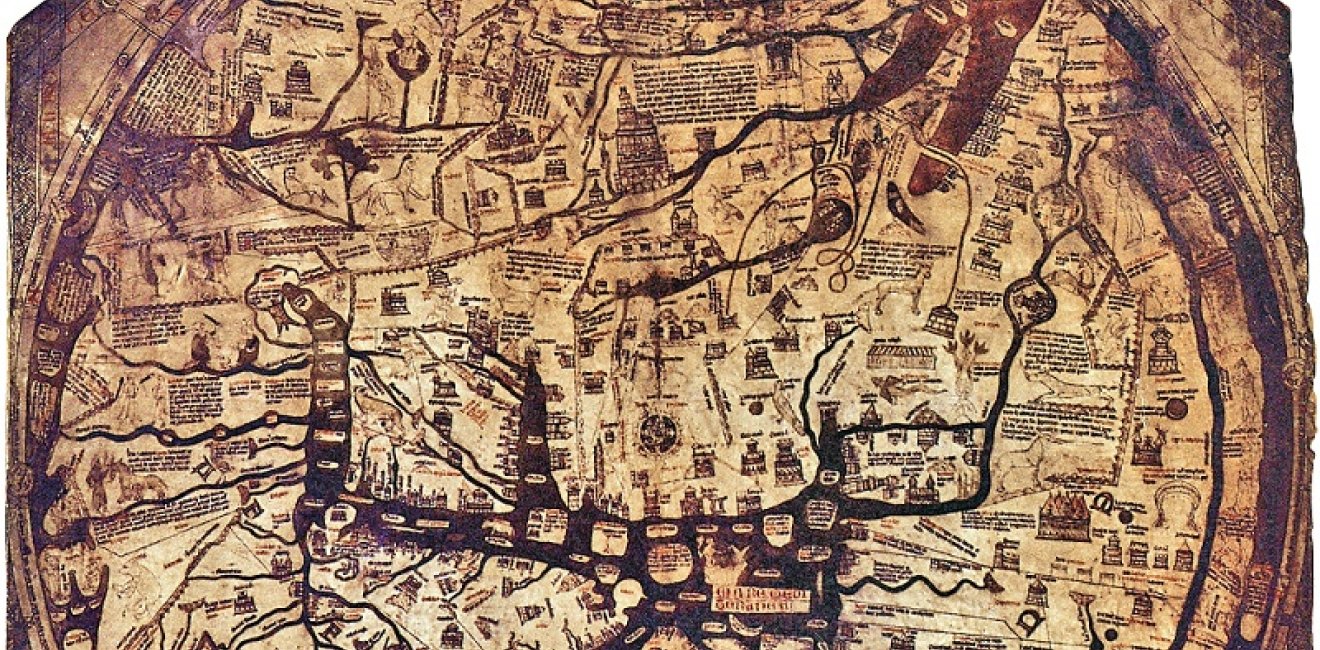

I don’t want to write another academic monograph few people will read, so I am presenting my research in short-form publications and exploring non-traditional ways to present my research. For example, I am working on developing an interactive website, so people can explore the spaces of medieval and early modern eastern Europe and Eurasia through maps, images, objects, texts, etc., like the map above (more on this map below). I am also working on a public history project using computer games to teach people about medieval Europe, Russia, and Eurasia. I want my research to reach as large an audience as possible, so I am always looking for creative and engaging ways to present my work.

Q: How did you become interested in your current research topic?

My early work on this topic began when I was first at the Wilson Center, which coincided with the twentieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. There was a lot of reflection on what the term “Eastern Europe” meant and whether this was still a meaningful way to describe the region, especially with the EU’s recent expansion to the east. So, I began to look for when this concept was created. This led me to Larry’s Wolff’s book, Inventing Eastern Europe, which was published in 1994 and argues that the western idea of eastern Europe first developed not during the Cold War but during the Enlightenment. It was uncanny, because almost every single example he used can also be found in medieval sources. It was history repeating, because while people during both the Cold War and the Enlightenment invented a nearer near east for Europe, it had happened many times before, especially during the Middle Ages, which was the first time Europeans and Eurasians had sustained contact with each other.

I wondered why this region kept being invented and reinvented for centuries as an other to “the West.” Why did medieval travelers write that had entered an entirely different world as soon as they crossed the Oder? Why did medieval world maps, like the Hereford Mappa Mundi above, depict so-called “wonders of the East”—like Cynocephali (dog-headed people) and ostriches, which supposedly walked on hooves and ate iron—in Eastern Europe? Eastern Europe and Eurasia are on the middle left because medieval maps are oriented to the east (oriens), not the north. If you want to see these images and explore these fascinating maps in more detail, check out Virtual Mappa 2.0.

Q: Why do you believe that your research matters to a wider audience?

Six years ago, the American Historical Association began #EverythingHasaHistory, which demonstrates that “history can inform our understanding of everything and that historians' voices are essential in conversations about current events.” I believe this, and I also would argue that the history of anything is usually much deeper than most people realize. That the history of the distant past—or at least what people think they understand about the history of the distant past—matters in current events was most forcefully presented to me in 2009 by the fact that many of the books I ordered from the Library of Congress on medieval Eastern European history had an NSDAP stamp on them. The Nazis invented their version of Eastern Europe using medieval European inventions of eastern Europe, but they were not the only ones who drew on the knowledge of scholars of the deep past. “The Inquiry,” which began meeting in 1917 to advise Woodrow Wilson on the creation of the post-WWI world, included many scholars of ancient, medieval, and early modern history who, among other things, helped to invent interwar Eastern Europe.

Q: What is the most challenging aspect of your research?

There are actually two. One pertains to the way professional historians are trained, and the other relates specifically to my project. I initially had some misgivings about undertaking such a huge project, because historians are trained in graduate school to focus their research narrowly and told that they must conduct all their research in the original languages, preferably using the original sources in archives. They also have to master the historiography (the history of the history written about something) of anything even marginally related to their research. I am unable to do these things consistently in my current project, which is liberating in many ways. These language and research requirements are one of the main reasons it takes, on average, eight years to get a PhD in History in the United States. It’s absurd that it should take longer to get a PhD in History then it would take to get both a JD and an MD. This specialized training can also prevent historians from asking big questions and makes it more difficult for historians to make their research relatable to people who are not specialists in their field.

This was made clear to me as a recently minted PhD during my first tenure at the Center. I presented my research as I would at an academic conference on medieval studies, and almost every single person in the room looked like I was speaking a language they couldn’t understand, which I essentially was. No one asked any questions except one person who walked up to me afterward with a look of genuine concern on his face and simply asked “Why?” It wasn’t until then that I realized how incredibly esoteric my research seemed to most people and that the traditional ways historians present their research are not the best ways to explain to smart, busy non-historians with too many other things to think about why the Middle Ages matter. This is one of the reasons I have been focusing on games and food in my research and teaching. If I just start talking about medieval history, I often lose people. But, if I begin by connecting what I am talking about to what my audience or students ate for breakfast or the games they just played on their phone, then it is instantly relatable, because these are things people in the past and present have in common. Games and food are also great topics because they allow the people I am engaging with to explore differences and change over time in more informal and unconventional ways, like playing games and cooking recipes. I want to help people understand my research by engaging in experimental, experiential, collaborative, and creative research with them.

Q: What do you hope the impact of your research will be?

I hope that people will think about what the history of the deeper past can contribute to how we understand the world today. During the Middle Ages the world was connected for the first time in a very long time, not just at the end with the rise of European colonialism, but throughout and usually through the agency of non-Europeans. In recent years there has been a growing emphasis on studying these interconnections in the Global Middle Ages, as it is called. I want my research to contribute to this important intellectual movement while also reaching a broad audience, some of whom, I hope, may see some value in using my research to analyze current events.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Author

Associate Professor, University of Arizona

Kennan Institute

The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more