This article is also available in Spanish (see below).

In a recent intervention at the general debate of the United Nations’ General Assembly, President Peña Nieto unveiled a decision that had long been awaited by scholars working on Mexican foreign policy. In a cautious manner, emphasizing that this would be done in “accordance with the normative principles established in our Constitution”, he announced that Mexico would now participate in the United Nations’ Peacekeeping Operations (PKO’s).

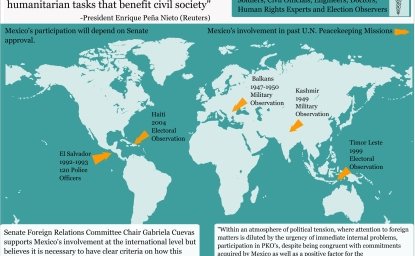

In fact, this is not Mexico’s first experience with PKO’s. The best-known instance involved the deployment of 120 policemen in El Salvador as part of ONUSAL, which remains as one of the most paradigmatic examples of the new generation of PKO’s that arose after the end of the Cold War. These gradually acquired multiple responsibilities have quietly re-interpreted certain principles of the UN’s Charter, such as those relating to non-intervention in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of States.

In effect, the ONUSAL - along with many others implemented since - participated in the elaboration of a new Constitution, the organization of elections, the supervision of agreements concerning human rights, the re-incorporation of former combatants into civil life, and the creation of a civil registry.

We have no clear explanation for the strong animosity that came to prevail amongst the ranks of Mexican Government towards participation in such operations. We can sense the influence of certain personalities within the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, who were averse to risks that they perceived as unnecessary, such as joining the Security Council, or taking part in international actions that were far from Mexico’s immediate interests. It can also be attributed to the popularity of extremely varied points of view within the Ministry of Defense: from a rather traditionalist sense of nationalism, to somewhat erroneous notions regarding the process that must be followed for the creation of a PKO and for States to decide their participation. The fear of ever seeing “blue helmets” in Mexico probably lay behind many such viewpoints.

When a PKO was created in 2004 to contribute to the stabilization of Haiti (MINUSTAH), Latin American nations were at the forefront. With Brazil at the helm, Argentina, Chile and Uruguay were quick to follow, and they actively sought Mexico’s participation. This search became even more insistent after the earthquake of 2010, which further deepened the desperate situation in Haiti, where both humanitarian assistance and forces to maintain order were urgently required. Mexico’s response remained negative.

This reluctance, inexplicable to many, became a matter of controversy amongst decision makers and analysts of Mexican foreign policy. Positions became polarized, and the matter entered the terrain of “politically delicate decisions,” despite the fact that polls indicated that neither leaders nor the general public had any predisposition against such operations. Many seminars in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, many debates within the Ministries of Defense and the Navy, and certain changes in the attitudes of both ministries regarding external cooperation were needed for the tide to turn.

Meanwhile, PKO’s had acquired a growing importance within the UN. On the one hand, they became the dominant issue on the Security Council’s agenda; long sessions are devoted there to make decisions on PKO´s that guarantee their utmost efficiency, such as the clarity of their mandates, dates for their termination or conditions for their renewal or enlargement, financing responsibility, adequate reporting. Their participants’ preparation in matters of human rights became a priority.

Simultaneously, participation in PKO’s has become a central criterion to evaluate the degree of commitment amongst member states of the UN towards the restoration and maintenance of peace. Without being a panacea, they are viewed as the Security Council’s most tangible asset for the creation of the necessary conditions for economic development and democratic life, particularly in the world’s most disadvantaged regions.

Their scope and level of success has been varied. In the case of Bosnia, their contribution for peace was very much put into question. In other cases, PKO’s have been an important factor for the reconstruction needed after military conflicts, for the establishment of civil institutions, for helping to cope with natural disasters and, or, for building a new Nation State.

Peña Nieto’s decision is neither unprecedented, nor does it assume commitments that had not been previously undertaken during the signing of the United Nations Charter in 1945. It is worth remembering that article 43 in Chapter VII of this very document refers specifically to the obligation of Member States to display solidarity with actions determined by the Security Council to maintain or restore peace, including the deployment of military forces.

The decision announced at the UN has probably been consulted with the Ministries of Defense and the Navy, where the matter of foreign relations changed considerably after the experience gained during the presidency of Felipe Calderón. The traditional unease regarding the outside world eased as cooperation with the United States grew in the struggle against drugs trafficking. Many members of both the Army and the Navy were trained in the United States, United States military advisors traveled to Mexico, and ties between both nations’ intelligence agencies became, and remain, very close.

In this context, given that hostility towards external cooperation in military affairs has somehow vanished, the idea that certain members of the armed forces, along with experts of civilian groups in the fields of health, elections or education, could integrate a contingent to participate in PKO’s appeared attractive. It was in keeping with the slogan of “Transforming Mexico,” actively promoted by the government of Peña Nieto. Furthermore, the opportunity for military elements to interact with other armed forces, familiarizing themselves with the techniques for the organization of joint actions amongst groups from diverse systems, getting to know different societies and broadening their international perspective, could well contribute to their professionalization.

However, diverse internal circumstances have eclipsed the attractive aspects of this decision. Firstly, it has coincided with an extremely grave matter such as the alleged execution of 22 young people by military elements in Tlatlaya, State of Mexico, in June. Media repercussions have ballooned after these events were made public in September, attracting enormous attention both on the national and international levels, casting doubts on the military’s image regarding human rights, and indeed, on the very notion of Mexico as a State based on the rule of law.

Secondly, the decision to take part in PKO’s has been used by left-wing parties in the Senate to attack the presidency. During Foreign Minister Meade’s presentation of the section on foreign policy of the Annual Report presented by the President for consideration by Congress, Senators from the PRD, PT and Movimiento Ciudadano expressed their strong disapproval of this decision based largely on three arguments: not having previously consulted the Senate, which has the faculty of authorizing the deployment of troops outside Mexican borders; unnecessarily endangering the physical integrity of participants; and diverting resources and energies that are needed internally.

Within an atmosphere of political tension, where attention to foreign matters is diluted by the urgency of immediate internal problems, participation in PKO’s, despite being congruent with commitments acquired by Mexico as well as a positive factor for the internationalization of military and civilian groups, has failed to capture the interest of popular imagination. In reality, it does not contribute substantially to face the challenges of a foreign policy which, given the transformations that have recently occurred both nationally and internationally, lie elsewhere.

Mexico City, October 12, 2014