In a landmark 2006 election, the Palestinians rejected the long-standing political status quo and turned over power to Islamists through the ballot box. It was a stunning upset. Hamas trumped Fatah, the party of Yasser Arafat, which had dominated Palestinian political life for almost a half-century. Even Hamas was surprised by the outcome.

The victory of an Islamist party had a wide-ranging effect on both the Palestinian Authority (PA) and the greater Middle East.

The breakthrough was not expected to happen that way. Hamas, an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood, made the strategic decision to run for the first time in 2006. It expected to win a fair share of seats and then lead the opposition from inside the system. Fatah calculated that the shift would integrate its primary opposition into the system but under its control. Even Palestinian pollsters predicted that Fatah would win a majority and continue to govern the not-quite-state.

Instead, Hamas won an outright majority of parliamentary seats. It abruptly had to shift from being an underground movement to running government ministries and forming a legislative agenda. The transformation has been one of the most profound in Islamist politics. Hamas—formally known as the Movement of Islamic Resistance -- had been formed to provide Palestinians with an alternative to the secular and nationalist movements that had led Palestinians in the past. But it was never designed to be a governing political party.

Instead, Hamas was designed at its inception in 1987 to show that Islamists were not only concerned with prayer and religious practice but that they could also actively defend Palestinian interests by force of arms. After mainstream Palestinian leaders embarked on a peace process with Israel in the 1990s, Hamas stood outside and insisted on continuing “resistance” in all forms—including attacks on Israeli civilians.

So when it won the 2006 elections, Hamas had to figure out how to be a resistance organization, a religious movement, and a governing party all at the same time. Its task was made more difficult by a cutoff of funds from the international community and diplomatic isolation. A year after Hamas’s victory, a brief civil war split the PA into its two geographic parts. Hamas emerged in uncontested control of Gaza, but it was tossed out of power and driven partly back underground in the West Bank.

Western countries, led by the United States, spearheaded an effort to outmaneuver Hamas, isolate it, and even oust it from power. As an alternative, they provided diplomatic and financial support to the West Bank government headed by President Mahmoud Abbas of Fatah and Prime Minister Salam Fayyad, a technocrat. That strategy clearly failed with Abbas limping on, linked to a peace process that delivered few victories and Fayyad finally leaving office in 2013.

But Hamas also faced severe problems after the Arab uprisings of 2011. It initially hoped to capitalize on the Muslim Brotherhood’s rise in Egypt all the way to the presidency. But the Brotherhood’s abrupt ouster by the military in 2013 and worsening relations with other regional backers led the Hamas leadership for forge an understanding with Abbas in the spring of 2014. The two rival Palestinian factions agreed to form a new cabinet that would then try to reunify the West Bank and Gaza. The agreement was skeletal; it left unanswered many questions about how (or even whether) it could be implemented.

But political progress was short-lived. In mid-2014, Israel launched a massive military assault on Gaza, after blaming Hamas for the murder of three Israeli hitchhikers in the West Bank. The conflict went on for almost two months. The aftermath left the plans of all parties in shambles: Hamas had no answers on how to break Israel’s longstanding siege of Gaza. Abbas had no ideas on a diplomatic peace process. And Israel faced an unbowed Hamas.

By early 2015, Hamas was still deeply entrenched in Gaza, despite the political despair and physical destruction. The array of factors against it—Israel’s military might, Fatah’s fury, the creation of a Palestinian technocratic cabinet, and even its own recognition that it owed Gazans something more—did nothing to not dislodge Hamas from power.

The Beginning

Hamas constantly boasts that it grew out of the remnants of the Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood. The Egyptian Brotherhood had encouraged Palestinians to form their own chapter while Palestine was under British Mandate. In 1948, when the British withdrew from Palestine, the Egyptian Brotherhood mobilized followers to support the Palestinians in the war against the Zionist movement. The war ended with Israel’s creation on more than three-quarters of the territory of Palestine.

The bitter defeat meant dispersal for the Palestinian Brotherhood; its remnants were too discouraged to undertake political activity for many years. Some in the West Bank joined the Jordanian Brotherhood. (Jordan annexed the West Bank and controlled it in the wake of the 1948 war until 1967.) Palestinians in Gaza had little freedom to maneuver because, until 1967, they were under control of an Egyptian regime hostile to the Brotherhood.

Some Palestinian Islamists who had migrated outside of Palestine—especially to other Arab countries—tried to organize independently. But most first gravitated to Fatah, a movement that actually had many former Brotherhood members among its founders.

The 1967 war brought the West Bank and Gaza under Israeli control. The Brotherhood’s political positions were hardly friendly to Israel’s policy—or even Israel’s existence. But the movement’s insistence that Palestine had to become more Islamic before it was liberated seemed a welcome gift to Israeli security officials, who allowed the Islamists some freedom to pursue their social and religious activities.

As a result, tensions deepened among Palestinian groups in the 1970s and 1980s. Other Palestinian movements criticized the Brotherhood for abandoning politics. In turn, Islamists were repelled by the collection of leftist and nationalist ideologies prevailing in Palestinian resistance circles. When Islamists became active, their goal was often as much to contest the local influence of non-Islamist groups as to resist Israel. The bitter rivalry led to intense, occasionally even physical battles for control of organizations as well as Palestinian loyalties.

Israel’s Role

Over time, Israel’s decision to use the Islamists as a counterweight to resistance groups gradually helped the Brotherhood breed a new generation of activists who pushed to move beyond religion and use social activities as the base for politics. At the same time, a new generation of Palestinian leaders also emerged in Kuwait, Jordan, and Egypt to generate momentum behind Islamists joining the resistance.

By the late 1980s, the disparate efforts coalesced to launch the Islamic Resistance Movement—or Hamas, its Arabic acronym—to ensure the presence of an Islamist participant in the Palestinian struggle. The new movement was most visible in Gaza, but West Bank Islamists joined in early as well. Hamas formally announced its existence when the first Palestinian uprising, or Intifada, erupted against Israeli occupation in 1987.

Over the next few years, Hamas led major attacks against Israeli targets, transforming the relationship. Israeli occupation authorities, who had viewed the Islamist movement as a quiescent alternative to nationalists and leftists, suddenly confronted the reality of an armed, militant, and well-organized opposition willing to use religion to justify violence. And attempts to crush the organization through arrests, detentions, and expulsions were decidedly unsuccessful.

The underground resistance organization also soon became far more politically active—and powerful—than the Brotherhood that had spawned it. The decision to engage in both politics and armed action came at a time that other Islamist groups in the Arab world were also stepping up political involvement. Hamas’s founders may have been influenced by this trend. But they may also have been inspired by the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Iran was hardly a political model, but the idea of an Islamic-flavored revolutionary movement inspired some Palestinians.

A Militant Wing

Unlike other Brotherhood movements that tried to operate through legal channels where possible, Hamas totally rejected the Israeli occupation and demonstrated no qualms about using violence. In the 1980s, Israel’s arrests of Hamas leaders led the movement to create a clandestine military wing. The various branches of Hamas—which was by now part social movement, part militia, and part political party and was spread throughout the West Bank, Gaza, and the Diaspora—coordinated remarkably well, given the geographic separation and diverse priorities. The various wings of Hamas—political, social service, and military—worked hard to coordinate while maintaining their separate priorities.

By the late 1980s, Hamas had sufficient standing that it was a serious alternative to the long-dominant nationalist and leftist factions. The Islamist group did not reject cooperation with other movements. But its terms for joining the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO)—the umbrella organization then gaining international acceptance as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people—included a large representation in all PLO bodies. The price proved too high for the PLO leadership. But Hamas made inroads in all other parts of Palestinian society, from universities to the refugee camps.

During this phase, the political positions of Hamas remained uncompromising. It insisted that Palestine should be liberated from the river to the sea—meaning it refused to recognize Israel. Armed struggle was justified to attain that end

Hamas showed some signs of flexibility, although whether this flexibility was tactical or a real hint of moderation was always unclear—and leaders themselves probably differed. Hamas did offer, for instance, to negotiate a truce of defined duration with Israel. And it suggested at times that it would accept a Palestinian state limited to the West Bank and Gaza as long as it did not have to recognize Israel.

The Peace Process

In 1993, the Oslo Accords signed by PLO leader Yasser Arafat dramatically altered the political environment for Hamas. The agreement between the PLO and Israel created the Palestinian Authority to govern civil and security affairs of parts of the West Bank and Gaza. The PA created ministries, wrote laws, and drafted a constitutional framework as the basis of an eventual Palestinian state. In 1996, it held the first presidential and parliamentary elections.

During this second phase, Hamas joined smaller Palestinian factions in rejecting the Oslo Accords. It declared that the Israeli occupation had not ended, so neither would the resistance. Indeed, in the early Oslo period, Hamas increased attacks on Israeli civilians, especially after the massacre of Palestinian worshippers by an Israeli settler in Hebron in 1994.

But Hamas could not ignore the challenges posed by the Palestinian Authority. It clashed with the new Palestinian security forces. Under heavy pressure from Israel and the United States to gain control, the PA tried to squeeze Hamas, especially after Hamas’s bombing campaign of 1994.

The Palestinian Authority also established patronage that obscured distinctions between institutions of the proto-state and Arafat’s personal political machine in Fatah, which left Hamas (somewhat willingly, perhaps) out in the cold. Hamas faced profound short-term challenges as the PA won an initial burst of popular support simply through the prospect of statehood, even as it moved against other Palestinians in Hamas.

The peace process offered some opportunities for Hamas, however. As daily management of civil affairs in the West Bank and Gaza passed from Israeli to Palestinian hands, Hamas gained a bit more freedom to maneuver, especially in nonpolitical affairs and social services. In contrast, the PA’s standing in Palestinian society sometimes placed limits on what PA security officials felt comfortable doing.

The First Elections

Palestinian elections posed a particularly vexing issue for Hamas. The movement was anxious to prove its popular standing but also to withhold its blessing from any part of the Oslo process.

After a series of internal debates throughout the 1990s, Hamas leaders made four basic shifts. First, they declared that they wanted no part of violence among Palestinians and would therefore react with restraint to PA forces. The one major caveat was that Hamas followers would defend themselves if forced to do so. Hamas largely held to this stance, even when its leaders and followers were arrested and tortured.

Second, after some hesitation, the movement decided not to enter the 1996 parliamentary and presidential elections. A splinter Hamas group did run candidates, scoring modest successes. Although they stayed away from national elections, Hamas leaders suggested that they might run in local elections—a stand that made Fatah repeatedly postpone the polls.

Third, the movement generally scaled back its “resistance,” anxious not to provoke PA repression or popular ire as a result of the harsh Israeli countermeasures. There were some spectacular exceptions, however, notably in in 2012 and 2014, when Hamas leaders exploitd deadlocks in the peace process to show that Hamas offered an alternative strategy.

Finally, Islamists in general turned their emphasis from the political sphere—where the cards were temporarily stacked against them—to social, educational, and charitable work.

Hamas also softened some of its positions on political issues, although gradually. The language used by key leaders became less religious and more political. (As long as Hamas’s opposition to Israel was framed in religious terms, compromise was difficult.)

The second intifada in 2000 constituted a turning point as pivotal as the Oslo Accords. “Resistance” was suddenly the common denominator for all Palestinian groups, and Hamas seized a leadership role. In response, Israel escalated its own campaign, including the assassination of several Hamas leaders. But Hamas’s ability to operate independently of the skills or charisma of particular individuals paid off handsomely. The elimination of senior officials seemed to leave no permanent scar on Hamas’s capabilities.

After the second intifada, Hamas emerged with enhanced political credentials. The organization was far healthier than any of its rivals. And it had avoided being tainted by association with the Palestinian Authority, which was widely seen as not only irrelevant and impotent but venal as well.

The 2006 Election

By 2006, Hamas had a hard-earned if bloody reputation for promoting the Palestinian cause. Fatah, by contrast, was associated with decay, corruption, and infighting. Both factors contributed to Hamas’s stunning upset in the January parliamentary elections. Fatah also sabotaged its own prospects by running too many candidates, who ended up taking votes away from each other.

Unprepared for its sudden electoral success, Hamas tried to form a coalition government, but other parties balked. International actors, led by the United States, refused to transfer vital assistance to the new government unless it immediately accepted specific conditions, including renouncing violence and accepting the binding nature of past agreements. Israel, which collected taxes for the PA, also refused to turn over revenue to the Hamas government. And Fatah, which still controlled the PA presidency, the bureaucracy, and the security services, sought to undermine Hamas through any means possible, including strikes and threats of dissolving the new parliament.

So Hamas first had to go into the government alone. It faced international boycotts, fiscal strangulation, and strikes by government workers, but it held firm. A national unity government between Fatah and Hamas was briefly brokered in early 2007, but by the spring intermittent violence erupted between the two groups, especially in Gaza. As Egypt, Jordan, and the United States provided material support to forces under Fatah control, Hamas moved against security forces under Fatah’s control in Gaza.

Gaza’s brief and brutal civil war in 2007 was mirrored in the West Bank, where President Mahmoud Abbas fired the Hamas-led government and replaced it with technocrats. The West Bank leadership sought to purge Hamas supporters from public institutions in the West Bank, while Hamas moved against Fatah in Gaza.

Three Big Issues

The tensions presented Hamas with difficult choices. Its platform pledged to reform Palestinian society along Islamic lines, to resist Israel, and to provide viable government. But since 2007, Hamas has struggled over which path to emphasize.

The first path emphasizes the group’s Islamist agenda. Since its founding in Egypt in 1928, the Muslim Brotherhood has always emphasized reforming the individual and the society along Islamic lines. But to win the 2006 elections, Hamas downplayed Islam. It focused on promoting political reform and ending corruption rather than on a specific religious agenda.

After 2007, however, some Hamas activists sought to use the movement’s ascendance to bring Palestine’s legal framework and public life into line with Islamic values and teachings. The activists were generally held back by the Hamas leadership, which gave priority to political and governance issues. But in 2012, Hamas moved to rebuild a broader Muslim Brotherhood organization, which may mean some return to a religious agenda for some parts of the movement.

The second path for Hamas emphasizes resistance, literally the movement’s middle name. Yet as with the Islamist agenda of Hamas, its pursuit of resistance has been uneven since 2007. It fired rockets from Gaza—but with the declared aim of securing a cease-fire with Israel on more favorable terms. And when an indirectly negotiated cease-fire did take hold, Hamas largely observed it and even enforced it on other factions.

Hamas’s third path is governing, the preferred course of action for a normal political party. But Hamas has not seen itself as a normal political party. Leaders present the movement as the “un-Fatah” in every respect. Fatah had become mired in corruption, unwilling to share political power, and unable to protect the Palestinian Authority against Israeli assault. Fatah leaders showed a proclivity for writing laws and then violating them when they did not suit Fatah’s needs.

Hamas promised in 2006 to take a different path: it would reluctantly govern, but it would distinguish between party and government. But it, too, abandoned its pledge after seizing power in Gaza in June 2007. No longer the un-Fatah, Hamas harassed political opponents, sought to control nongovernmental organizations, and bent the law. It also had its own scandals.

Oddly, for an ideological movement, Hamas has been fairly short on specifics on either a political program or basic issues. Leaders often cite two core ideological documents, but neither seems to guide the movement in practice.

The Hamas charter from the late 1980s is a hodgepodge of blustering, militant positions and conspiracy theories, edging at times into anti-Semitism. The charter is almost never mentioned by its members, some of whom seem embarrassed by its contents. The second document is the platform from the 2006 elections, which is far more restrained and focuses on issues of governance and political reform. After 2006, Hamas members of parliament and ministers often cited it as almost a contract with Palestinian voters. But its contents have largely been forgotten since the Palestinian split in 2007.

In the tumultuous decade since it opted to participate in elections, Hamas has been a political paradox. By early 2015, the movement had not abandoned or altered its early commitments to Islamization, resistance and governance, even though individual leaders clearly had different emphases and priorities. Yet Hamas prideditself on practicality in day-to-day decisions. In effect, the movement prioritized governing—the source of greatest daily pressure—while clinging fast to its general principles in other areas.

Key Positions

The political positions of Hamas are broad and sometimes ill defined, much like its ideological commitments.

Israel

The movement is at its most loquacious on issues involving the struggle with Israel, but there is vagueness even here. Hamas has clearly stated that it does not accept Israel. But it will accept a Palestinian state on the 1967 borders. Precisely what will be on the far side of that border is unclear. Hamas has hinted that it might reach a modus vivendi with Israel. It has also suggested that it might abide by a Palestinian peace agreement with Israel, even if the movement itself opposes that agreement. But these are mere hints, and individual Hamas leaders sometimes seem to differ on where they stand.

Democracy

Democracy did not play much of a role in the group’s early thinking, but Hamas does claim to internally follow democratic procedures. In the 1990s, while it was repressed by the PA, Hamas also began to emphasize human rights and rule of law.

Hamas’s 2006 electoral triumph increased its rhetorical commitment to democracy. In 2012, however, its leaders seem to want decision making by consensus among Palestinians rather than democratic vote. Like many political actors, Hamas’s enthusiasm for elections waxes and wanes with the group’s standing in the polls.

Islam

Hamas is unquestionably Islamic in orientation, but it also describes itself as a wasatiyya, or centrist, movement dedicated to moderation, flexibility, and gradualism in applying Islamic norms to public life. That description gives its positions a socially conservative flavor, but Hamas is generally willing to admit a wide variety of interpretations and postpone demands to apply Islamic law in the short term.

The Future

For the Islamic Resistance Movement, putting governance above Islam and resistance may seem a surprising choice. Hamas’s leaders seem to want to show that they can rule Gaza efficiently and pursue international diplomacy even if it means postponing other parts of the group’s mission. But ruling Gaza is clearly not the organization’s ultimate goal.

The Arab uprisings of 2011 initially seemed to offer Hamas a way to break out of its isolation. Between 2011 and 2013, the two years after Egypt’s uprising, Hamas took small steps to expand its horizons. It exploited a regional climate more conducive to Islamist parties. It took advantage of the West Bank leaders’ failure to achieve peace with Israel. Hamas toned down its ideological rhetoric, then moved to reconcile with Fatah. It even sent officials on diplomatic missions across the region. Hamas also announced an intention to build a comprehensive Muslim Brotherhood organization.

But the Brotherhood’s ouster from power in Egypt, in 2013, abruptly reversed the fortunes of Hamas too. The new Egyptian leadership, under a former field marshall, did not hide its hostility to Hamas. It enforced a stringent blockade of people and goods to Gaza.

In 2014, Hamas was unable to defend the population of Gaza from Israeli airstrikes during a 50-day confrontation over the summer. Gazans also became increasingly dependent on international assistance to help rebuild the area. By early 2015, Hamas’s path of politicization had produced a paradox: The movement could not be ignored nor driven from power. But its leaders also had few achievements to boast about beyond the movement’s mere survival.

Nathan J. Brown is professor of political science and international affairs at George Washington University. He is also a nonresident senior associate of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. His most recent book is When Victory Is Not an Option: Islamist Movements in Arab Politics (2012). His website is http://home.gwu.edu/~nbrown.

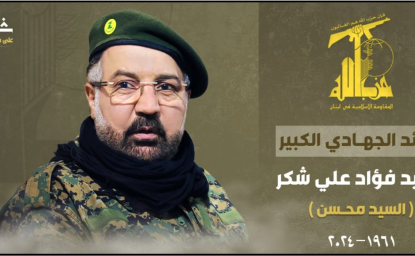

Photo credits: Hamas flag by Bluedenim [CC-BY-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons; Khaled Meshaal by Trango (Own work) [CC-BY-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The Islamists

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Israel Escalates Attacks in Gaza: What’s Next?

The Gaza Ceasefire and Its Aftermath: Danger and Opportunity