At the beginning of 2021, where is ISIS most active in Syria? And Iraq? And what are its targets—people, places, institutions, governments, what else?

ISIS is struggling to maintain operations along the Kurdish-Arab ethnic fault lines in Iraq as well as along the Euphrates River in northeast Syria. In both areas it is engaging in low-level insurgencies, with a limited ability to hold terrain or launch complex attacks. ISIS is more significant in the government-held areas of Syria, especially in the Badiya desert south of the Euphrates and east of Palmyra. It intermittently holds some terrain there and is frequently able to cut off local communications. Its main targets are local tribal and community leadership and local security forces. Aside from attacks, its main activities are intimidation and financial shakedowns of local merchants and farmers. It is also trying to develop international capabilities, such as training and dispatching terrorists beyond Syria and Iraq. ISIS is also very difficult to totally annihilate, given both sympathy from and its intimidation of the local Arab populations.

How strong is ISIS and who are its members—what percentage is local and what percentage is foreign fighters? Where do those foreign fighters come from? And is ISIS still able to recruit foreigners and get them across borders?

ISIS leaders view all of Iraq and Syria as one front. People, weapons and funds flow fairly easily throughout the area. ISIS is estimated to have between 8,000 and 16,000 fighters, but little is known about whether they are full-time or part-time. The vast majority are locals from the former caliphate, or from elsewhere in Iraq or Syria. The percentage of foreign fighters in ISIS is way down from the period between 2013 and 2016. The flow of foreign fighters has dropped partly because of a shortage of supply and partly because of better policing by Turkey of the routes into Syria.

How has ISIS adapted its recruitment tactics since the fall of the caliphate? How is ISIS financing its operations, especially since many earlier sources of revenue, such as Syrian oil, have been cut off?

ISIS still has highly sophisticated social media platforms. Its appeal to potential recruits appears similar to the period of the caliphate. It is distinguished from al Qaeda by the emphasis on acting in the here-and-now and jihadist writings that serve the ISIS cause.

Its local recruitment in Iraq and Syria is also fueled by its anti-Shiite ideology and opposition to the (apostate) government in Damascus and the (Shiite-dominated) government in Baghdad. Funding is primarily generated by local shakedowns, smuggling and other economic activity by ISIS cells.

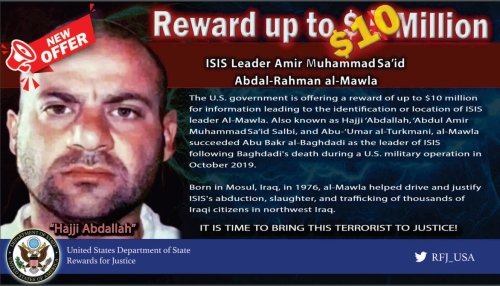

What is known about the new ISIS leader, Muhammad Said Abdal Rahman al Mawla? How is he different from Abu Bakr al Baghdadi? Does he have the same authority? Is he a tactical mastermind or a symbolic religious emir? Where is he? Who are his top lieutenants?

Very little is known about him. The general assumption in the campaign to defeat ISIS is that the top leadership is much weaker since al Baghdadi’s death in 2019. But the organization still generates sufficiently motivated and experienced mid-level lieutenants to sustain operations at current levels.

How does ISIS operate now that it is dispersed and entirely underground? Is its Shura Council still operating? Does al Mawla rule by edict or does ISIS make decisions by consensus of the Shura?

There is some sort of Shura Council, but its role is obscure. It does have a strategic plan, with an emphasis on operations along the Iraq-Syria front and in particular in Diyala province in Iraq.

Whither jihadism? There have been roughly three generations of transnational jihadi fighters: Afghanistan in the 1980s, Al Qaeda in the 1990s-2000s and the Islamic State and its affiliates in the 2010s. Each has been more militant, recruited more widely, and had deadlier goals. What worries you about jihadism next? And where?

This is both a sociological question and one for terrorism experts. ISIS, or Daesh, was a byproduct of both the Arab Spring in 2011 and the failure of traditional security mechanisms to stop the expansion of Iran and Shiite Islam into Sunni Arab areas. There may be no fourth generation, given the current situation—relative stability throughout the region compared to the period between 2011 and 2020; relative containment of Iranian advances in the Arab world; and greater limits on the dissemination of jihadist ideology, influence and resources out of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

What was the most difficult challenge that you faced in the campaign against ISIS?

The resiliency of the organization—both the level of fighting forces and its roots in local communities. Both were not insurmountable but required both time and extraordinary military and other resources.

What are the top challenges that the Biden administration faces on ISIS and jihadism more broadly?

There are four obvious challenges and one wild card: First, ISIS and al Qaeda in West Africa; second, ISIS and al Qaeda in Afghanistan; third, ISIS strength in the government-controlled areas of Syria; and fourth, the perpetual risk in the Sunni Arab areas of Iraq of an outbreak of jihadi resistance against the Shiite-dominated government and Iran’s influence. The wild card is a mass casualty event—masterminded or launched by ISIS or al Qaeda—outside of the Middle East.

Author

Former ambassador to Iraq and Turkey, and Special Envoy to the Global Coalition To Defeat ISIS

The Islamists

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more

Middle East Program

The Wilson Center’s Middle East Program serves as a crucial resource for the policymaking community and beyond, providing analyses and research that helps inform US foreign policymaking, stimulates public debate, and expands knowledge about issues in the wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

An Act of Terror Cannot Occur on Russian Soil

US Intel: ISIS, al Qaeda, Hamas, & Hezbollah