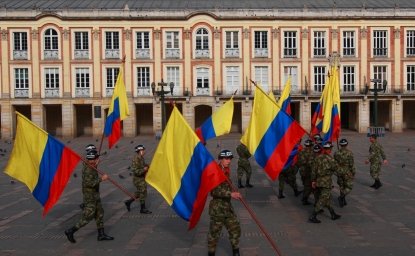

June 23rd marked a watershed in the history of Colombia’s internal armed conflict, which has claimed the lives of some 220,000 people, displaced upwards of 6 million people, and caused untold suffering and economic damage for the country as a whole. With UN Secretary Ban Ki Moon and the presidents of Chile, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and Venezuela looking on, the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia signed an accord on bilateral ceasefire and FARC disarmament. The document also laid out the specific mechanisms for the concentration and disarmament of the FARC’s 6-7,000 fighters and included new security provisions to protect demobilized fighters and civil society activists in the post-war era. Notably, the document showed the FARC’s acceptance of a government-proposed popular referendum on the peace treaty—rather than what it hoped would be a Constituent Assembly which would have had far greater powers. The government’s proposal for a plebiscite is still under consideration by the country’s Constitutional Court.

The signing of a final peace accord is still weeks off, but the June 23rd agreement marks a transcendent step. After more than half a century of war—and amidst widespread skepticism the FARC was serious about the peace talks—the FARC has agreed, at least on paper, to lay down its weapons and transform itself from a military into a legal political force. In so doing it has embraced Colombia’s existing political and legal framework, a stark recognition that the decades-long effort to overthrow or replace Colombia’s institutions and state structure has failed.

As arduous it is to get to any peace agreement—and these talks have been going on for 4 years—the real difficulty lies ahead. Peace accords are not panaceas, but rather, a new set of opportunities that can be seized or squandered. The government will have to fulfill vast commitments regarding rural development, the effective reintegration of demobilized combatants, and the transformation of illegal economies, including narcotrafficking. This will take resources, institutional capacity, the full engagement of Colombia’s private sector and civil society, and efforts to overcome the fractiousness of Colombian politics, including a vigorous opposition to the peace agreements led by former president Álvaro Uribe.

The signing of a final peace accord is still weeks off, but the June 23rd agreement marks a transcendent step.

One of the biggest challenges for the Colombian state will be to occupy the spaces left by the FARC’s demobilization. Despite the enormous security gains of the last decade and a half, vast areas of the countryside are not under effective government control. Fostering inclusive and sustainable rural development, and linking rural economies to urban centers, will be a prodigious challenge, one that has never been attained in Colombia’s history. Preventing criminal organizations—and the smaller yet still-active National Liberation Army (ELN)—from taking advantage of FARC demobilization will require the presence of security as well as civilian institutions. Colombia’s criminal economies are well developed and will not end with the stroke of a pen; indeed, evidence suggests that criminal organizations have grown stronger during the peace talks. The likelihood that some number of FARC commanders will continue their involvement in the lucrative drug trade is high. Peace accords elsewhere in Latin America have shown the great capacity of one form of violence to mutate into another. Sadly, Colombia already has a long history of such violent transformation.

That said, the scope of the difficulties should not detract from the significance of the current moment. Ending the conflict with the FARC—efforts that have taken place and failed since the early 1980s—removes an insidious source of violence, human rights abuse, and economic destruction. Building on the government’s security gains, and during the period of the FARCs unilateral ceasefire, aspects of the rural, licit economy have begun to flourish. Tens of thousands of former combatants, many of them FARC deserters, are building new lives, studying, and finding a niche in the productive economy. It is easy to be cynical in the face of so many obstacles to a peaceful future. But new spaces and possibilities are opening and that itself should be a cause for celebration.

The opinions expressed here are solely those of the author.