Dr. Susanne Spahn is a political scientist, historian, and journalist based in Berlin.

Read the interview in Russian HERE.

Q: To what extent is the voice of Russian journalists heard in Germany?

A: The German public generally gets little information through the Russian press; the news from Russia usually comes via German information agencies and from German correspondents. Few Russian journalists are known by name, with the exception of those who were murdered, such as Anna Politkovskaya, or had to emigrate, such as Zhanna Nemtsova. The German media write about such journalists in detail. Other than that, knowledge about Russian journalists and more generally about the Russian press is very limited. Starting in 2015, the Dekoder online platform has been translating articles from the independent Russian media to fill this gap.

Q: Do the German media draw a distinction between the work of Russian independent journalists and that of propagandist channels?

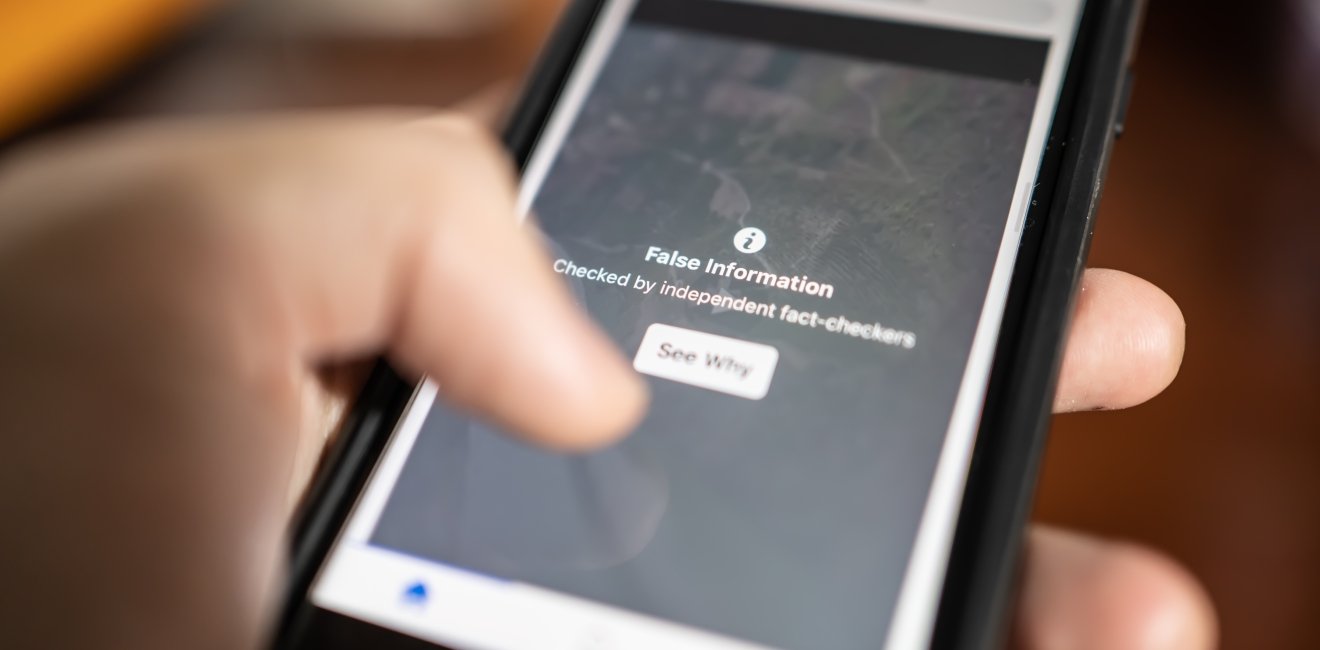

A: This difference is widely known. The story of a girl named Lisa that unfolded in January 2016 demonstrated to the public how Russian state-affiliated media disseminate false information and how it is used as a political tool. A correspondent of a Russian state television channel invented the story of a girl from a German family of Russian descent who had allegedly been raped by migrants. Then multiple Russian media spread this story, and Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov expressed his concern about “our Lisa” and accused the German authorities of allegedly trying to sweep this case under the rug. Thus it became clear that Russia sees around three million Russian-speaking residents of Germany as “compatriots” and that the Russian state sees it as its task to protect this community. Insofar as most Russian-speaking residents of Germany have German citizenship, Russia’s claims are met with a high degree of criticism in Germany. Russian-speaking residents of Germany consume the content of Russian state media, including television, via cable, satellite, or online, so the impact of Russian disinformation on this group is especially strong. RT Deutsch and Sputnik News are the ones that primarily address the German-speaking audience, and their popularity in Germany is on the rise.

On the one hand, reports by RT and Sputnik, which now operate as RT DE and SNA, are critically covered by some media outlets. On the other hand, many outlets, primarily the German television talk shows, tend to offer the platform to representatives of Russian state-affiliated media (here one should primarily mention the former editor-in-chief of RT DE Ivan Rodionov and the former head of the RIA Novosti office Dmitry Tulchinskiy). Lately, however, the media presence of these journalists has gone down.

The German public and the government still do not treat the problem of disinformation spread by the Russian state-affiliated media with appropriate seriousness, except for the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution. When the coronavirus crisis struck in March 2020, RT and Sputnik launched a campaign of disinformation, in the course of which they denied the pandemic and called such preventive measures as handwashing meaningless. This prompted the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution to warn the public about disinformation perpetrated by the Russian media. RT DE is under surveillance by the office because this channel undermines the trust of people in democracy.

In its latest report, the EU Stratcom Task Force presents alarming figures: according to them, Germany is in the crosshairs of the Russian disinformation campaign, with 700 disinformation cases identified since 2015. It is far ahead of France, which comes next, with 300 cases. Based on that, many German media have started to address the topic of Russian disinformation. I have also contributed to raising public awareness with my studies published by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom. These studies are available in Russian too.

There is little information on the work of independent Russian journalists. As a rule, their names come up in connection with high-profile political disclosures. An example is the investigation of Alexei Navalny’s poisoning by FSB agents, which was carried out with the participation of the independent online newspaper The Insider.

Q: Are there Russian media that people in Germany pay more attention to and cite more often and that can be considered influential? For instance, the reverse influence certainly exists, and Der Spiegel magazine and Die Welt newspaper are the obvious leaders among the German media in terms of their citation rates in Russia.

A: Readers of interregional newspapers and people interested in what is going on in Eastern Europe know Novaya Gazeta, TV Rain, and Meduza as independent media. Echo of Moscow radio is also considered a media outlet that offers its platform to the opposition, even though it is part of Gazprom Media holding, which is close to the government. However, Russian outlets are not featured in the 2020 ranking of the most cited media put together by the German statistical portal Statista. Meanwhile, in number of detained journalists, Russia ranked eighth in the world in 2020, right after Iran and Vietnam. Thanks to the publications on repressive legislation and foreign agent legislation in particular, it is widely known in Germany that there is a problem with freedom of the press in Russia. The fact that international media and journalists face pressure in Russia more and more frequently is also a matter of concern.

Q: What is the attitude in Germany toward Russian propagandist media, such as Russia Today, Sputnik, the Rossiya television channel, Vesti radio, and the like?

A: German-language portals of RT and Sputnik have been active in Germany since 2014 and recently assumed the names RT DE and SNA. The strategy of RT DE and SNA is to present themselves as an independent alternative. They accuse the so-called mainstream media of concealing the truth and serving the elites. Thanks to this strategy, RT and Sputnik are gaining popularity among that part of the audience that has lost trust in traditional media and refers to the latter as the “lying press.” Russian state media seem to these people to be a better alternative. And it is of no concern to them that RT, Sputnik, and other such channels are funded by the government and controlled by the Russian presidential administration, thus being neither alternative nor independent in reality. The audience for RT and Sputnik either does not realize or disregards this misuse of terms.

RT and Sputnik use the crises to present the German government or the EU as powerless and incapable of solving problems and contrast them with Russia, its political leadership, and President Putin as efficient managers. One could observe this during the refugee crisis, during Brexit, and now, in the course of the coronavirus pandemic. These media favorably cover protests of any kind, for instance the anti-Islam movement Pegida, as well as rallies of the Querdenker group, which criticizes the COVID-19 pandemic containment measures. During the public protests, correspondents of the Ruptly video agency constantly report live from the scene. Here one can clearly sense the desire to purposefully show those who fight against the system and use them as an asset in the information war. This is how editor-in-chief of RT Margarita Simonyan described it in her interview with Lenta.ru. And this is what one can with a high degree of accuracy observe and register based on this channel’s content.

This strategy is clearly successful, especially for RT DE. In internal email correspondence published by Der Spiegel, editor-in-chief of RT DE Dinara Toktosunova praised the editorial team for the fact that thanks to its coverage of the coronavirus pandemic, viewer numbers increased by 41 percent, and from January to September 2020 RT DE reached an audience of 14 million people.

These successes are confirmed by data in the public domain: RT DE has over a million subscribers to its main social media platforms (Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter)—an impressive figure. On Facebook, RT DE has already surpassed the German-language service of Deutsche Welle. New social media Redfish and Maffick Media also enjoy high popularity. In the Now channel offered by Maffick Media has over five million subscribers on Facebook. However, it is an English-language channel and thus it targets an international audience. Both Redfish and Maffick Media are subsidiaries of Ruptly and present themselves as independent and alternative. Maffick Media even indicates an address in Los Angeles, which creates the impression that it is a U.S. company.

Here we see that Moscow media strategists are extremely creative and constantly developing new formats to reach new population groups. RT DE and Sputnik have in recent years turned into platforms for right-wing populist content (the Alternative for Germany party in particular), while the target audience of Redfish is rather the left-leaning, critically inclined public. Maffick Media via the Waste-ED channel reaches out to those who are interested in environmental issues. In the meantime, In the Now offers primarily entertainment for a young, apolitical audience, while discreetly adding political content to the mix.

In the run-up to the Bundestag election in 2017, regional elections in 2018, and European Parliament election in 2019, RT Deutsch and Sputnik tried to influence public opinion and provided media support to the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany party and the Left Party, offering them a wide space for self-presentation, including in the form of interviews. One knows that supporters of these parties also are critical of democracy and represent another group of opponents of the system who traditionally get media support from RT and Sputnik. The public does not know anything about the audience composition of RT and Sputnik, but based on their information agenda, it can be surmised that supporters of Alternative for Germany and the Left Party are a crucial target group.

Q: How does the German legislation treat Russian state-owned media? Are they considered regular media or the tools of state propaganda? Is their activity in Germany restricted in any way or may it be restricted in the future?

A: The federal government almost never publicly talks about the problem of disinformation disseminated by Russia. As far as I know, there are no laws regulating the treatment of Russian propagandist channels. Unfortunately, there is also no consensus on the fact that RT DE, SNA, and the like are political tools rather than regular media. Thus, in the past, federal ministers used to give exclusive interviews to RT Deutsch before the elections, reaffirming by their actions that what the channel does is journalism. It would be desirable to take a clear stance on this matter. For instance, French president Emmanuel Macron called RT and Sputnik the agents of influence. It would also make sense to create a nationwide agency in charge of media matters using the example of the British Ofcom [the UK’s communications regulator]. In the UK, a fine of £200,000 was imposed on RT for violating journalistic standards.

Another problem is insufficient transparency. Russian state media should be required to include the following information right on their home page: “This content is funded by the Russian government.” This transparency is needed because RT and the like present themselves as alternative and independent media. For instance, the new social network Maffick Media conceals its Russian origin, misrepresenting itself as an American company and thus misleading its users.

At present, the activities of Russian state media in Germany are not restricted, but the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution is monitoring RT DE because of disinformation and antidemocratic tendencies. Today, the RT DE channel is available online only, but before the end of this year it plans to launch full-scale TV broadcasting. Its studio in the Berlin district of Adlershof is already expanding, and 200 new journalists are to be hired. However, German law prevents state-affiliated channels from obtaining a license, so it will be interesting to see how RT DE plans to solve that issue.

Q: How do you assess the prospects of cooperation between German media and Russian independent journalists in a situation where Russia is unfolding repressive legislation on “foreign agents,” “undesirable organizations,” and so on? To what extent, in your opinion, can it complicate the relationship between Russian journalists and their European colleagues?

A: The interest in cooperation is high, but the consequences of repressive legislation have a huge negative impact. Many independent Russian journalists fear getting labeled as foreign agents as a result of collaboration with the German media. Since the times of the USSR, this expression has been used to indicate traitors. In Germany it is a matter of concern that critical and independent journalism in Russia has become practically impossible because journalists face financial fines and prison sentences. For that reason, German coordinators consider it a more viable option to work with Russian journalists who have emigrated.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.