I. Introduction

US-China competition has been intensifying in Southeast Asia, a region of immense strategic significance given its economic heft, geostrategic location next to major sea lanes, and diplomatic convening power via the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Amid this, there have been rising conversations about how Southeast Asian states are responding in this competition and the implications for Washington, Beijing, and other interested actors. For US policymakers in particular, this could have important effects on how Washington thinks about advancing key regional priorities such as diversifying supply chains and securing the first island chain extending out to the South China Sea.

This policy brief explores the agency of Southeast Asian states amid US-China competition and ways interested actors can boost it. It is informed by conversations with policymakers and experts across all 11 countries in Southeast Asia, which included multiple trips across the region. The brief makes three main arguments: First, the contours of US-China competition are such that it represents one of manifold challenges for Southeast Asian states, wherein Washington and Beijing bring to bear different capabilities. Second, Southeast Asian states are already exercising agency within this competition through engagement, balancing, and shaping their environment. Third, actors (including the US and its partners) can help reinforce the agency of Southeast Asian states to advance a shared vision for a region that is free from coercion and conducive to open and fair competition.

II. Contours of US-China Competition in Southeast Asia

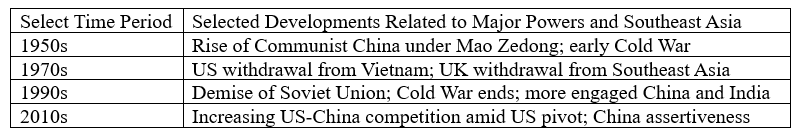

US-China competition is the latest in a series of phases of major power competition in Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia was under major power influence for centuries–from empires and open maritime routes linking it to China, India, the Middle East, and Europe to colonization. Southeast Asian states have also adjusted to multiple balance of power shifts over the decades. Those include the 1950s, with the advent of the Cold War in Asia; the 1970s with the US withdrawal from Vietnam, and Sino-US rapprochement; the 1990s with the Soviet Union’s demise and a more engaged China and India; and the 2010s with increasing US-China competition and Washington’s response (as illustrated in documents such as the 2018 National Defense Strategy). The lesson for much of Southeast Asia amid this reality is that exercising agency is essential to preserving autonomy.

As former Thai foreign minister Thanat Khoman once succinctly observed, without agency, smaller countries would “become nothing but mere pawns of different size.”

Today, as important as US-China competition is, it is also just one of a series of pressing priorities for Southeast Asian policymakers in their quest to manage challenges and maximize opportunities for growth and security. These include growing domestic pressures on regimes to deliver for their people; stresses on regional institutions such as ASEAN amid the proliferation of crises from Myanmar to the South China Sea, and minilateral institutions such as the Quad and AUKUS; and challenges to the rule of law, trade, and globalization. While aspects of US-China competition may offer sectoral opportunities for countries in areas such as semiconductors, the bigger worry is that this binary lens may disrupt Southeast Asia’s status as the world’s fifth-largest economy, with a market of nearly 700 million people and modestly high growth rates. For instance, Singapore’s new fourth-generation of leaders, led by Lawrence Wong, have verbalized worries of US-China competition derailing the so-called “Asian century” unless actions are taken by regional states.

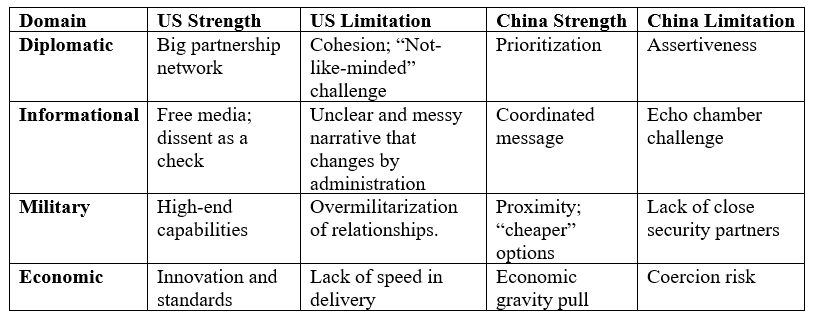

Within this evolving competition, the US and China have different capabilities. This can begin to be discerned (non-exhaustively) by employing the so-called DIME framework, which analyzes the diplomatic, informational, military, and economic realms (see table below). For instance, the US has strengths across DIME–including its allied and partnership network, free media environment, and innovative foreign companies. But it also has limitations, including the lesser weight given to diplomatic resources relative to the military, as well as the difficulty of crafting a clear narrative that sustainably aligns a diverse domestic stakeholders in areas such as advancing a more active trade policy. An additional challenge is crafting policies that are both attractive to Southeast Asia but can also be sustained over time in the US domestic context despite changes in administrations. Within Southeast Asia, US strengths tend to be more visible to long-term security allies such as the Philippines or developed commercial and strategic hubs, including Singapore. Washington’s limitations play out more in relatively less like-minded and lesser-developed countries, with Cambodia being a case in point in recent years.

Unsurprisingly, US and Chinese regional visions have built on their strengths. Take, for instance, Washington’s free and open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy, which has been sustained with some adjustments across administrations. In Southeast Asia, this combines areas such as values, partnerships, and military power, with lines of effort ranging from boosting partner maritime defense capacity to expanding development financing and people-to-people programs. Meanwhile, China’s so-called “community of common destiny for mankind” (CCD) in Southeast Asia uses Beijing’s strengths, such as its geographic proximity and economic heft as the region’s top trading partner and a leading investor. Manifestations have included Belt and Road Initiative projects, subregional initiatives such as the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation mechanism, and the gradual development of security institutions and exercises. China is also leveraging its involvement in agreements, including the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a pact that Washington was ineligible to join at the time due to the absence of a US-ASEAN free trade agreement relative to other ASEAN dialogue partners.

III. Evolving Complex Regional Realities in US-China Competition

The contours of US-China competition are playing out amid complex, evolving regional realities. The dynamics of US-China competition in Southeast Asia are at times portrayed through lenses such as Southeast Asian states resisting choices being forced upon them by Beijing and Washington, or individual choices such as the China links in Malaysia’s multibillion-dollar 1MDB scandal or the ongoing reporting on alleged Chinese naval facilities in Cambodia, despite Phnom Penh’s denials. But more granularly, Southeast Asian states are contending with complex regional realities that relate to how countries think and act in an environment of multiple powers with respect to three areas: outlooks, actions, and perceptions.

In terms of outlooks, though Washington and Beijing have tried to shape competing visions, Southeast Asian states have engaged with them only selectively as they also strive for a more inclusive, multipolar region.

China’s CCD was initially met with wariness in parts of the region. One official described it to the author as a “China-first concept in an Asia-first disguise” to create an exclusive China-Southeast Asia community reinforcing Beijing’s dominance. Meanwhile, the US FOIP generated anxieties within parts of ASEAN about how a reaction to China’s assertiveness by Washington–welcomed by some–could nonetheless lead Beijing to push back against efforts to counter its influence and even generate regional instability. This partly explains why the grouping’s ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific ended up trying to shift the Indo-Pacific conversation away from geopolitics and toward concrete regional priorities such as connectivity and sustainable development, which would also include other actors beyond Washington and Beijing, including India. This balance between preserving the region’s quest for growth and managing geopolitical challenges was a consistent theme in conversations with regional policymakers.

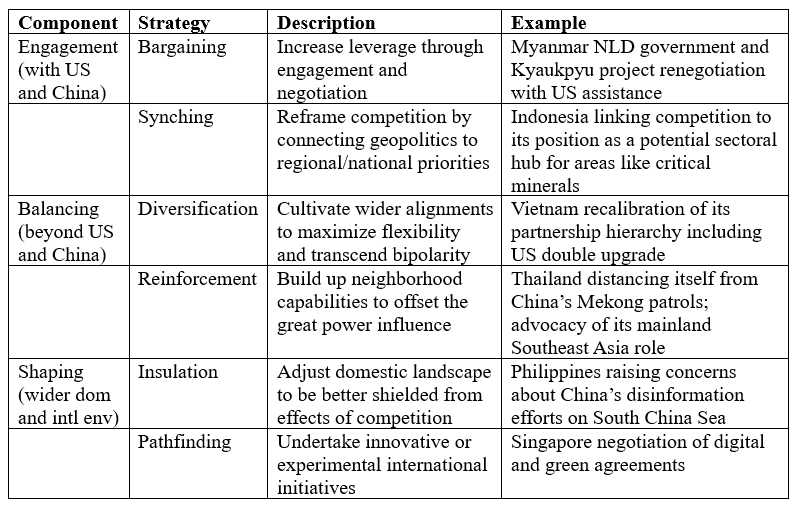

Turning to the second area of actions, Southeast Asian states have tried to affect US-China competition in various ways, classified here through the categories of engaging, shaping, and balancing (see table below for a summary, with the caveat that though countries are classified by strategy in the examples, most employ multiple strategies simultaneously). This constitutes one aspect of their agency amid competition, which can be defined simply as exercising their capacity to act. In the engaging component, one strategy is “bargaining” to renegotiate terms, such as Myanmar’s scaling back of the Chinese-backed Kyaukpyu project within the Belt and Road Initiative, with US assistance. Countries have also used “synching” to connect US-China competition to national priorities, such as Indonesia trying to attract investment, including from Beijing and Washington in sectors like critical minerals. Turning to balancing, one strategy is “diversification.” This is typified by Vietnam’s upgrading of its partnerships amid concerns about China, including the one with the US. A less appreciated one is “reinforcement,” where countries consolidate neighborhood positions to offset foreign influence. An example here is what officials privately acknowledge about Thailand’s sensitivities over issues such as the location of Chinese patrols in the Mekong subregion, and its reassertion of its own subregional strategic development frameworks such as the Ayeyawady-Chao Phraya-Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMECS). The third component of shaping has to do with how Southeast Asian states adjust their internal and external environments. One internal strategy is “insulation” to shield the domestic environment from major power competition, such as Philippine officials voicing concerns about Chinese disinformation efforts regarding the South China Sea. One external strategy is “pathfinding” through innovative sectoral approaches. We have seen this in particular in Indo-Pacific geoeconomic dynamics, with a case in point being Singapore trying to structure sectoral digital and green agreements such as the Digital Economic Partnership Agreement despite the challenging environment for whole free-trade pacts.

The third component is perceptions. Apart from how Southeast Asian states think and act, there is often also an array of domestic views on some of the manifestations of US-China competition among some Southeast Asian elites and the general population that may not necessarily be represented in national decisions. At a more superficial level, this can be seen in polling data, such as the overwhelmingly positive views of the US among the Vietnamese people relative to the caution in US-Vietnam ties exercised by the Communist Part of Vietnam. More granularly, this can also be seen in sentiments regarding particular initiatives undertaken by Washington or Beijing. For example, while the governments of Cambodia and Laos are often portrayed as being overly close to China, officials from both these countries at times privately admit they need to be responsive to societal concerns as well, rather than just advancing domestic regime legitimation. More publicized aspects of this include the fallout from the giant proliferating Mekong scam networks and communities negatively affected by some Chinese infrastructure projects.

IV. Policy Implications

While it is clear that Southeast Asian countries have agency within the broader context of US-China competition, it is also true that exercising that agency is a complex and uneven reality in the region. How countries respond is also likely to shift if US-China competition continues globally and multidimensionally with varying levels of intensity over time and differences in breadth, scope, and extent. This in turn raises the question of how Southeast Asian states themselves, as well as interested countries, can help boost regional agency. For the US, boosting agency would not only support Southeast Asian states, but also help advance US interests. Ideally, efforts to strengthen agency would both decrease the risk of countries being coerced in how they make their choices, as well as increase the opportunities for Washington to work with selected states to advance a shared vision of a multipolar order rather than one dominated by China.

This effort to strengthen agency should obviously begin with Southeast Asian states themselves. At a minimum, governments should consider how to manage the impact of major power competition on core national functions that transcend particular regime interests, including the information environment and the so-called commanding heights of their economies, such as telecommunications. There are already instances of this at play, including Vietnam’s spotlighting of a component of indigenization within its technology ecosystem and societal initiatives in the Philippines on combating fake news, despite enduring challenges. Beyond this, more capable and willing Southeast Asian governments should continue to socialize more active notions of agency. Indonesia’s leadership role in keeping FOIP afloat is notable in this regard, as is Singapore’s leaders’ useful rhetorical distinction between passive hiding amid US-China competition and “active multi-engagement.” Non-governmental actors also have an important role to play in shaping conversations about agency and ensuring that US-China competition is taking into account needs of Southeast Asia’s citizens. Some of this builds on ongoing work, including efforts by the ASEAN-ISIS network (an association of think tanks recognized by ASEAN to foster regional cooperation and information exchange) at the Track Two level to continue to advocate for a more inclusive and well-rounded notion of Southeast Asia’s security. This will be especially critical as US-China competition plays out in subregional, cross-border spaces that transcend nation states, from the Mekong to the Andaman Sea to the Sulu-Sulawesi Sea.

The US and China also have a role to play. This starts with mindfulness of actions that undermine agency, be it China’s portrayal of US allies such as the Philippines as being American puppets or US strongarming countries such as Malaysia on 5G, which came across to some officials as a less collaborative way to address legitimate security concerns.

On the affirmative end, both sides should focus on upping their own competitiveness rather than undermining that of the other.

For example, for the US, some of the inroads it can make stem from what might be termed China’s “influence-trust gap” in parts of the region, where Beijing is seen as both the most capable and least trusted power. At the same time, the US cannot simply rely on Beijing’s missteps to make gains of its own. Washington’s focus should be on managing its “power-commitment gap.” In that gap, there are questions about its ability to translate capabilities to sustained regional commitment that can address regional needs, especially in the economic domain, given domestic difficulties in areas that include trade. Addressing that requires a comprehensive approach, including leveraging tools such as the Development Finance Corporation, working with partners and crafting a narrative that showcases what Washington already does in the region through a series of actors, including companies that go beyond security.

Other powers and interested actors also have an important role. Sectoral leadership can add to Southeast Asia’s choices and reinforce agency beyond what Beijing and Washington do, with cases in point including Japan’s leading role in infrastructure and Europe’s role in the green economy. Supporting broader objectives such as preserving the rules-based order can help refocus the attention on shared goals beyond a Chinese or Western agenda, as is the case with support by India or South Korea in response to coercive Chinese actions in the South China Sea. Actors with a global perspective such as the United Nations or International Monetary Fund also can continue to help socialize the hopeful narrative of Southeast Asia’s unique growth story, rather than a fearful one of a superpower battleground. This narrative puts the region at the center and empowers its countries instead of viewing them as objects of major powers.

Author

CEO and Founder, ASEAN Wonk Global, and Senior Columnist, The Diplomat

Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition

The Wahba Institute for Strategic Competition works to shape conversations and inspire meaningful action to strengthen technology, trade, infrastructure, and energy as part of American economic and global leadership that benefits the nation and the world. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

How US and South Korea Optimally Partner in Strategic Competition