Washington, D.C. came late to the American urban street mural movement. New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and Miami all embraced this very public art form earlier and with more enthusiasm than the stodgier national capital. As the city began to redevelop during the 1970s following a long period of declining real estate values, some developers commissioned established artists to spruce up underused buildings with murals usually depicting national events. In 1984, internationally acclaimed muralist Richard Hass painted a dramatic portrayal of a young Abraham Lincoln adjacent to the house in which the president died. The Department of the Interior halted the artist’s original plan to paint an accompanying mural of an older Lincoln on a building across the street, next to Ford’s Theater, the scene of President Lincoln’s assassination. Other murals followed, often commissioned by some of the city’s largest intuitions.

Unlike other cities, Washington’s street murals initially tended to be unconnected with community. Muralist G. Byron Peck began to change the pattern in the 1980s and 1990s when he covered various sites around town with street art portraying local notables and historic events. Other artists such as Aniekan Udofia began to work closely with communities to formulate images that gave proud expression to local identity.

In 2007 several artists and activists came together to form MuralsDC with the goal of replacing graffiti with artistic works to revitalize communities and teach young artists how to create street art of lasting impact. Over the past dozen years, MuralsDC has sponsored and maintained 85 murals by 50 artists in 46 neighborhoods around the community. These years paralleled the explosion of gentrification across the city and street art became a powerful reminder that D.C. had a significant life and a culture before the newcomers arrived.

Murals, however, easily fell victim as new development spread across the city. Most buyers were unconcerned about the fate of street art when they set about to tear down and replace properties. Few new property owners felt attachment to the stories of a world that existed before they arrived. Many of the city’s most important murals--such as Hass’s Lincoln mural--have been lost to development. With time, street art became a flash point between new residents and the communities they were replacing.

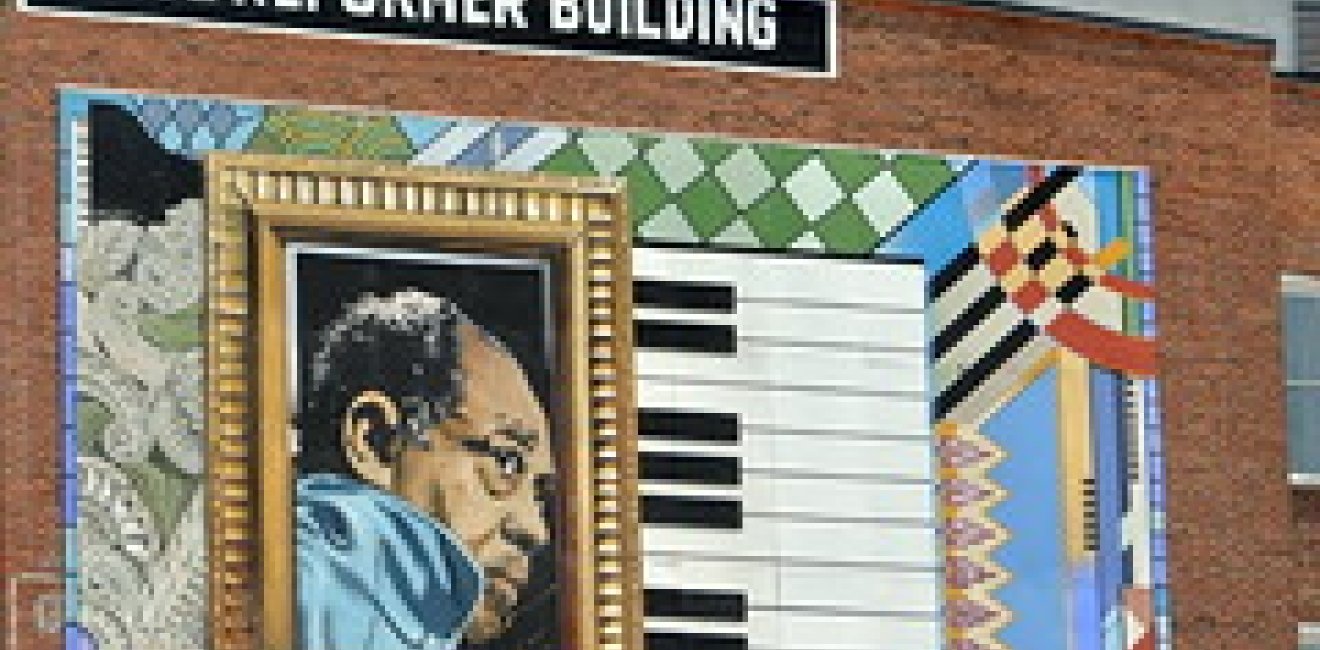

Peck’s stunning portrait of Duke Ellington on the side of U Street’s historic True Reformer Building held special claim in these struggles. Ellington not only grew up in the neighborhood; some of his very first performances were at the True Reformer headquarters of an important local African American fraternity. Visible from afar thanks to a brief break in the street line created by a metro entrance, Peck’s Ellington became an emblem of a creative past that was disappearing with every newly arriving resident.

By the mid-2010s, Peck’s Ellington succumbed to development. Many view this loss as a symbol of the obliteration of a long-standing African American cultural presence in the neighborhood. It occurred during the period when the area surrounding once proud main street of Jim Crow African American Washington had, like the city as a whole, become majority white. Together with MuralsDC, Humanities D.C. (the District’s equivalent to a state humanities council) commissioned Peck to recreate his original mural. On July 22, 2019, the community gathered at the True Reformer Building to celebrate Peck’s mural of D.C. homeboy Duke Ellington. The Duke’s return resonated throughout African American Washington following weeks of protest over the loss of another form of distinctive Washington urban culture deeply rooted in the African-American community.

Paintings and murals are only one small part of a larger resurgence in preserving D.C.’s cultural assets. The city’s streets were rocked throughout the spring by continuing demonstrations promoting D.C.’s signature sound: Go-Go. The rallies are continuing despite a resolution to the original spark that touched off the conflict.

As warm weather was making its way into the city in late April, a resident who had just moved into a new luxury apartment in the now trendy but historically African American Shaw neighborhood had lodged a complaint about loud music. For years, a small corner store--Metro PCS--had been blaring Go-Go onto the popular street corner of Georgia and Florida Avenues. The music spreading over the intersection had become a signature for a neighborhood that had survived decades of neglect.

The new arrival, who certainly had money and connections and has been assumed by many to be young and white, discovered that the music did not violate any local ordinances. Presuming a rightful place in the larger American social hierarchy, the newbie contacted the president of a phone company whose equipment was on sale at the small neighborhood outlet. The company leader, in turn, threatened to pull his products if the store did not stop playing the music.

Meanwhile, a few blocks away at the Howard University, students at the historic black college began to protest against neighborhood newcomers--who were white--for using their campus as a dog walk. In a moment too perfect to have been planned, a white resident told a TV reporter on camera that, if Howard didn’t want to be part of the new neighborhood, the university could just move out of town.

Washington for several years has been overwhelmed by a tsunami of gentrification that has forced the dislocation of numerous long-standing African American communities. Shaw, where these particular conflicts have been playing out, has been especially hard hit. Once the most prominent African American neighborhood in the city, the area has gone from over ninety percent African American to majority white, and overwhelmingly millennial, in the space of a couple of decades. This transition has left many African Americans feeling as if they are losing more than their homes and neighborhoods; they are losing a distinctive local culture and personal identity as well.

Hometown Washington, during the 1960s and 1970s, was the center of racial resistance to a white-dominated status quo. Ranging from social protest and civil unrest through economic empowerment and political activism, race dominated every aspect of Washington life in a city that had become majority Black. D.C. proudly became “Chocolate City” as residents embraced their identity. The strength of connections between identity and cultural expression that took shape during these years helps to explain the powerful backlash against gentrification and displacement today.

During the late 1960s, local musician Chuck Brown created an infectious musical style combining a distinctive Latin-tinged beat with a call-and-response vocal track that came to be known as Go-Go. The music emerged on Washington’s streets and in its rough and tumble nightclubs. Go-Go quickly became the anthem of D.C.’s African American working class, pounded out on plastic pails by kids at subway stations, appropriated by homegrown bands such as the Junk Yard Band coming out of the Barry Farms projects, promoted by popular groups such as Rare Essence, How Cold Sweat, and Shug-Go.

Alarmed at the disorder and crime sometimes associated with Go-Go venues, the city’s police carefully tracked performances, working with various licensing authorities to shut down clubs following violent incidences. The construction of a new baseball stadium for the Washington Nationals led to demolition of several popular venues. Residents of newly gentrifying neighborhoods used local neighborhood advisory boards to shut down several more Go-Go haunts. These attacks maddened the city’s black residents for whom Go-Go music and the culture surrounding it were essential elements of their identity.

In spring 2019, complaints by newcomers to traditional African American neighborhoods led to a powerful backlash against attempts to control the music. The complaint about Metro PCS prompted a petition signed by over 80,000 signatories demanding that the music continues to play on the streets. The communications company president who ordered the store to turn off the music relented and let it return. A massive Backyard Band concert and protest took over the intersection a few days later.

Those demonstrations prompted the #DontMuteDC movement, a new protest community, to hold gatherings often involving several thousand enthusiasts at major sites around the city. The movement shows no sign of abating, with celebrations of local music occurring almost weekly. The movement’s theme song, Don’t Mute DC, has become a local hit.

The city’s evolving racial mix reveals a great deal about tensions since a period when residents proudly proclaimed the District to be “Chocolate City.” According to Census data, the city moved from 35.0% black in 1950 to 53.9% black in 1960, on to a high of 71.1% black in 1970. Since that time, the percentage of the city’s population classified as black has declined steadily to 70.3% in 1980, 65.8% in 1990, 60.0% in 2000, 50.7% in 2010, and an estimated 47.1% in 2017. Meanwhile, the Washington metropolitan region has remained more or less one-quarter African American throughout. The departing D.C. black population is being displaced into nearby suburbs, primarily in Maryland’s Prince George’s County. The sense of loss over being forced from the city is no less real for having moved across an artificial political boundary.

When thinking about urban transformations we often turn to data to capture the social changes that have taken place. Statistics are powerful indicators of change in a city’s economic well-being, health, safety and security. If we look at recent data on per capita income in Washington, for example, we see that it has increased by over ten percent in recent years. On the surface, many measures would point toward vast improvement.

In 2017, the D.C. Government’s Commission on African American Affairs dug deeper and found that African American household income in the city was one-third white median household income. More astonishingly, the average net worth of white families was 81 times higher than the average family net worth of African American families. When viewed through the lens of stark racial inequality, the sense of losing out felt by many African American Washingtonians becomes powerfully explicable.

Returning to the music, city leaders can learn a great deal about their communities by engaging with locally-generated arts. In Washington, music, art and murals mark pride of place,. opening possibilities for bridging divides.

For the past several years, the D.C. Funk Parade has marched each May through the same protesting streets of Shaw. Activists launched the parade to bring various social groups, embracing both old timers and newcomers, together around a shared love of that funky beat that fortifies most local popular music forms. Tens of thousands marchers and spectators show up each year bringing together Washingtonians of every background. The difference between the sponsors of the funk parade and the complainers in their expensive new apartments is that the funk parade activists appreciate the city that was here before they showed up. The arts rather than data open up the possibility for such gratitude.

Image by Kevin Harber (CC BY 2.0), True Reformer Building, July 25, 2009

Author

Former Wilson Center Vice President for Programs (2014-2017); Director of the Comparative Urban Studies Program/Urban Sustainability Laboratory (1992-2017); Director of the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies (1989-2012) and Director of the Program on Global Sustainability and Resilience (2012-2014)

Urban Sustainability Laboratory

Since 1991, the Urban Sustainability Laboratory has advanced solutions to urban challenges—such as poverty, exclusion, insecurity, and environmental degradation—by promoting evidence-based research to support sustainable, equitable and peaceful cities. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Apprenticeships Are an Overlooked Path to Upward Mobility

Planning for Resilience In and After Conflict—A World Away