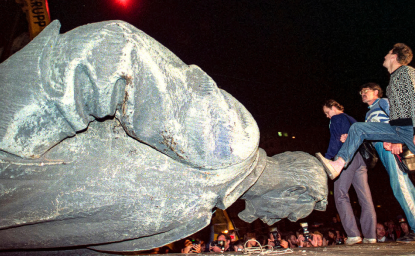

After four years of the phenomenon once optimistically dubbed the Arab Spring, the changes that have roiled those lands seem to have validated Robert Penn Warren’s quip that history, like nature, rarely jumps–and when it does, it usually jumps backward.

We can rationalize all we want–and accept that promoting democracy, good governance, gender equality, and respect for human rights takes time. (It took a century and half, a civil war, and a turbulent civil rights movement for the United States to even begin reconciling the promise of the Declaration of Independence with the reality that the U.S. Constitution validated slavery. And events in 2014 underscore that when it comes to matters of race there is still much work to do in this country.)

Trend lines in Arab lands seem to be running in the wrong direction. Four years on, the Arab Spring has degenerated into a catastrophe. Libya, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen are in varying degrees of civil war, insurgency and meltdown. Egypt, the largest and most important Arab state, appears to be less free and prosperous than it was under Hosni Mubarak. The kings and emirs in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Oman, Bahrain, Kuwait, Jordan and Morocco are stable and reasonably secure. But most are too busy looking in the rear-view mirror to undertake the kind of reforms that would head off their own day of reckoning.

Only Tunisia and Morocco seem to have come through the storm improved; and both are so idiosyncratic that they really can’t be used as models for the others. Lebanon has been a non-state for years, lacking a functional government able to control its sovereign territory; implement real reforms; or to manage Hezbollah, the country’s key power.

So why have things gone so wrong?

1. No leadership. Revolutions have, on occasion, produced strong leaders who have been capable of either unifying the state and/or reforming it. But the Arab Spring produced not a single leader who could rise above narrow partisan or sectarian affiliations to think about the interests of the nation as a whole, let alone establish a vision to transform it. Sectarian, tribal, and regional divisions continue to mock state authority. Nor has the Arab awakening produced transactional leaders who could competently manage and govern and put these countries on the road to security or prosperity.

2. No institutions. Forget great leaders. What about functioning institutions? Minus Tunisia, in the five countries fundamentally altered by the Arab Spring (Tunisia, Yemen, Libya, Syria, and Egypt) credible institutions rooted in the will and authority of the people either don’t exist or have been suppressed or coopted by the state. Yet without them–including empowered parliaments; respected judiciaries; a free press, and a robust civil society–it’s impossible to see how prosperity, security, and real politics will evolve. It is a cruel irony that the authoritarian kings and emirs have managed to survive and are the allies the U.S. relies on as partners in a turbulent region. Egypt’s process of reform and democratization is proving as empty under the generals as it was under the Muslim Brotherhood or Mr. Mubarak.

3. No cohesion. Arab states consolidated their authority and control from 1970 to 2011. Now the reverse has taken hold. Decentralization (Iraq), civil war and perhaps fragmentation (Syria, Libya, Yemen) remain the order of the day.

Meanwhile, it’s fascinating that the three most functional and significant states in the region are not Arab: Iran, Turkey, and Israel. All face major challenges. But all are politically stable, all have tremendous economic and technological capacity, and all are capable of projecting their power in the region. As the Arab world melts down, they are the powers to watch in 2015.

The Roman historian Tacitus observed that the best day after the death of a bad emperor is always the first day. Given what’s happened in Arab countries since the early, heady days in Tahrir Square four years ago, we can only hope Tacitus turns out to be wrong.

The opinions expressed here are solelly those of the author.

This article was originally published in The Wall Street Journal's Washington Wire.