The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) includes five Western Hemisphere countries, of which three (Chile, Mexico, and Peru) are in Latin America. Through the TPP, the United States would deepen its economic and strategic partnership with each. The agreement would update and enhance existing free trade agreements between the United States and these nations, a development that is especially important for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which was negotiated more than two decades ago. The TPP would improve the Latin American participants’ access to markets in Asia and boost their exports as a result, and it could also improve their ability to attract foreign direct investment and strengthen their participation in global value chains.

Equally important, however, would be the impact of TPP on those countries in the region that are not part of the agreement. Central American countries with significant apparel industries are particularly concerned about the potential impact of increased competition from Vietnamese producers, which will gain preferential access to the U.S. market, effectively chipping away at the privileged access to U.S. consumers provided by the Dominican Republic–Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR). The U.S. response to the concerns and interests of friends and allies in the region that are not currently a part of the TPP will be important to the coherence and strength of U.S. policy toward the region.

Strengthening Regional Value Chains

The United States and Mexico already work together to produce goods through an integrated North American manufacturing platform. Parts and materials regularly crisscross the borders of North America as goods are produced. This joint production strengthens regional competitiveness by allowing the United States, Canada, and Mexico to combine their comparative advantages and by allowing firms to achieve economies of scale. As a result, even imports from U.S. neighbors support the U.S. economy, with 40 percent of the value in final good imports from Mexico having originated in the United States. The U.S. content in imports from Canada averages 25 percent, but it is much lower in imports from China (4%), the European Union (2%), and others. The TPP would in some ways update NAFTA, adding disciplines such as cross-border data flows and biologic drugs that were not included in the original agreement.

The North American auto sector is especially integrated, and Mexico fought very hard to strengthen the auto rules of origin in the TPP, which ensure that TPP benefits only go to producers using a large percentage of parts manufactured by TPP countries. The TPP rules of origin require less than the Mexican auto sector hoped for, but it has declared its support for the agreement, citing improvements in market access in Asia and the Pacific.

Equally important, however, would be the impact of TPP on those countries in the region that are not part of the agreement.

The economies of Chile and Peru depend heavily on commodity sales to Asia, with China in particular purchasing a large portion of their exports. Although this orientation boosted their growth in the past decade, the slowing of China’s economic growth has proven a significant challenge. Chile and Peru have responded by seeking to diversify their economies, and both see the TPP as an opportunity to attract investment and insert themselves into global value chains in manufacturing and other commerce.

With similar goals in mind, in 2011 Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru launched their own economic integration effort, the Pacific Alliance. Because these countries have market-oriented approaches to economic development and strong relationships with the United States, the U.S. government has supported the Pacific Alliance and become an observer. Colombia, the only Pacific Alliance country not participating in the TPP negotiations, seems a strong candidate for future inclusion in the agreement, which would be an important tool for it to deepen its integration into regional and global value chains and continue to modernize its economy. Panama and Costa Rica have taken steps toward joining the Pacific Alliance and would also be strong potential TPP candidates.

Docking On to the TPP

As the TPP was being negotiated, only members of Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) were invited to join. Were it not for this unofficial requirement, the aforementioned countries of Colombia, Panama, and Costa Rica might well have been a part of the agreement. TPP was, however, designed to be dockable, meaning that additional countries can go through an application process to join it. If the TPP is implemented, the United States will face an important set of decisions on supporting Latin American partners that seek to join, perhaps pushing to waive the requirement of prior APEC membership or supporting the newcomers’ participation in APEC as well. Otherwise, U.S. policy toward Latin America risks incoherence, and U.S. partners may feel that the special relationships institutionalized through previous trade deals have become less special.

Setting Standards for Textiles and Apparel

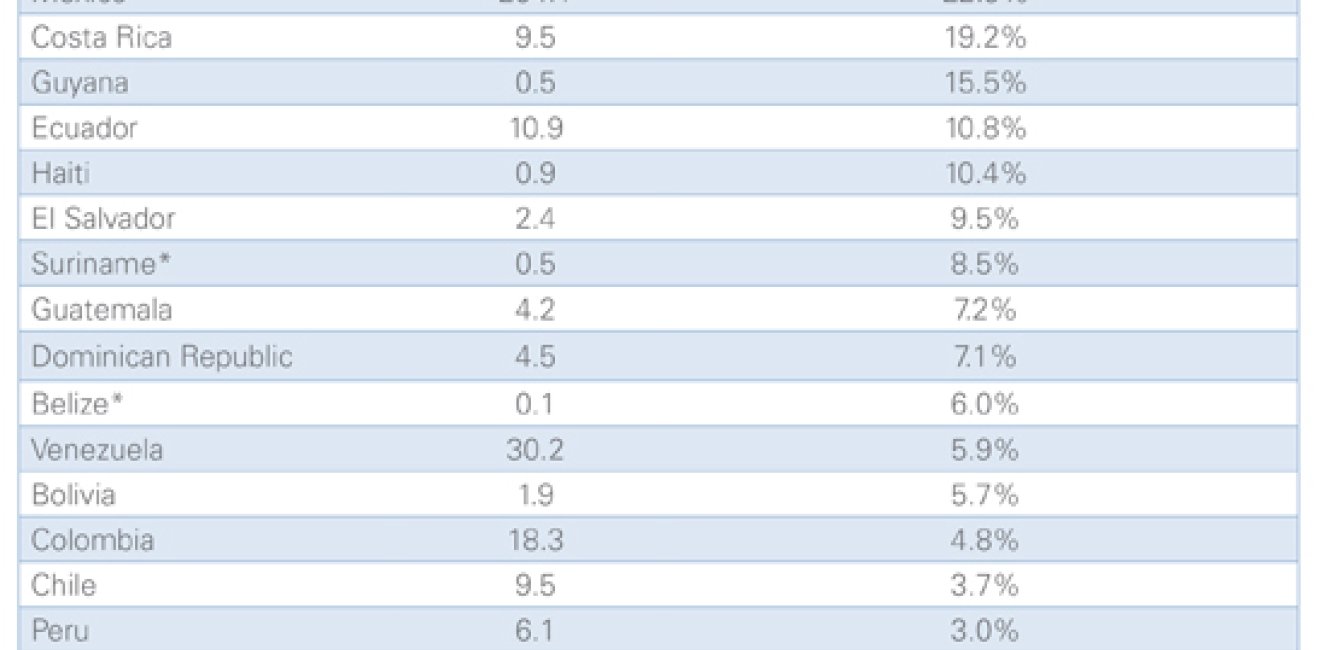

Several Central American and Caribbean economies depend heavily on exports to the United States (see table). Prominent among these exports are apparel products and upholstered furniture, usually made with U.S.-sourced textiles in order to meet the regional content rules in NAFTA, CAFTA, and the Caribbean Basin Initiative. TPP’s inclusion of Vietnam—a major apparel manufacturer that supplies most of its textile inputs from China and other Asian nations— is likely to collide with these established patterns of trade and may harm apparel manufacturers in the Western Hemisphere that depend on preferential access to the U.S. market. The TPP includes a “yarn forward” rule, which stipulates that only garments made in the TPP region with yarn and fabric also made in the TPP region qualify for tariff-free access to the TPP markets. These stipulations help protect U.S. textile suppliers but do less to protect apparel makers elsewhere in the hemisphere.

Source: World Bank Development Indicators (GDP); U.S. Census Bureau (exports to United States, reported as imports to United States)

Creating Divisions within Latin America?

The TPP does not aim to create divisions within Latin America, although it does further institutionalize contrast between participating countries’ pursuit of export- and market-oriented growth strategies and the more closed and currently out of balance economic models of countries such as Venezuela or Argentina. Brazil is not a TPP partner, but with a gross domestic product that is nearly half of Latin America’s combined total, it has an internal market large enough that it avoids much of the risk faced by other non-TPP Latin American countries of losing out on investments. The TPP presents the greatest risk of division in Latin America by potentially alienating countries that would like to join the TPP to increase participation in global value chains but have not yet been able to.

Conclusion

The United States already has free trade agreements in effect with each of the Latin American TPP countries, and they also have agreements in effect with each other. The TPP strengthens and updates these existing agreements, creating opportunities to deepen and expand regional supply chain integration, but given that each participating country already offers the others preferential access to its market, hemispheric trade volumes are unlikely to grow dramatically. Trans-Pacific trade, however, is likely to grow as barriers are eliminated. The TPP would increase U.S. and Latin American export opportunities to the fast-growing Asia-Pacific region, while also making the Latin American TPP countries more attractive to investors. At the same time, the hemisphere would be exposed to increased competition from Asian producers for imports to both Latin American and North American markets. The TPP is a useful but insufficient tool for Latin American countries to become more integrated into global value chains. To fully reap the rewards of opening new markets in Asia, Latin American partners will have to complement trade openings with domestic and regional efforts to boost competitiveness and innovation.

The opinions expressed here are solely those of the author.