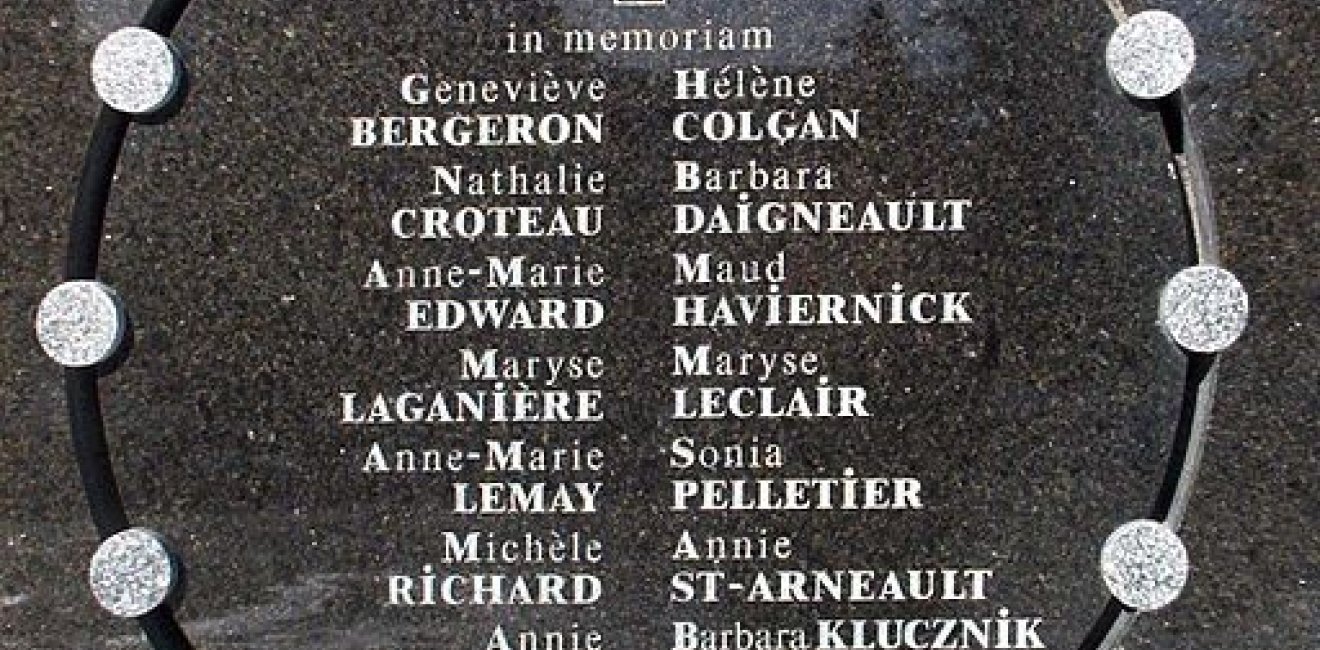

On December 6, 1989 a man entered an engineering classroom at Montreal’s École Polytechnique and murdered 14 young women: Geneviève Bergeron, Hélène Colgan, Nathalie Croteau, Barbara Daigneault, Anne-Marie Edward, Maud Haviernick, Barbara Klucznik-Widajewicz, Maryse Laganière, Maryse Leclair, Anne-Marie Lemay, Sonia Pelletier, Michèle Richard, Annie St-Arneault, and Annie Turcotte. Twelve of them were engineering students, one was a nursing student, and one was a university staff member.

Their murderer then killed himself. He left behind a one-page suicide note (in French) confirming that he went into the classroom to commit his act of violence specifically against women: “Feminists have always enraged me … I have decided to send the feminists, who have always ruined my life, to their Maker.”

The École Polytechnique shooting killed more people than any other mass murder in Canada during the 20th century. Thirty-one years later, it still resonates with Canadians. In 1991, Parliament declared December 6 to be an annual National Day of Remembrance and Action on Violence Against Women, with a White Ribbon to be worn in commemoration.

The Canadian government also established a nine-person Panel on Violence Against Women to study the diverse aspects of violence targeting women in Canada. The panel’s report, Changing the Landscape: Ending Violence, Achieving Equality was issued in 1993 and introduced the concept of zero tolerance (no level of violence is acceptable) and called on all organizations and institutions to review their programs, practices, and products in the context of zero tolerance policy, which includes an accountability framework, implementation steps, and a zero tolerance model for organizations and institutions to follow.

The École Polytechhnique massacre in 1989 was cited more than a dozen times in the United States Congress during debate related to the passage of the Violence Against Women Act, which became U.S. law in 1994, and the language of the act shows the clear influence of the Canadian Panel on Violence Against Women, its hearings, and its final report.

Thirty-one years later, the debate in Canada on violence against women has a renewed focus on its indigenous First Nations communities. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police reported in 2014 that 1,181 indigenous women were killed or went missing across the country between 1980 and 2012.

Shortly after his election in 2015, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau established a National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. The Inquiry issued its final report, Reclaiming Power and Place, on June 3, 2019 and its findings were harrowing: indigenous women and girls constitute 4 percent of the total female population of Canada but 16 percent of all female homicides.

Chief Commissioner Marion Buller, a retired judge who is Cree and a member of the Mistawasis First Nation in Saskatchewan said at the release of the inquiry report:

“Despite their different circumstances and backgrounds, all of the missing and murdered are connected by economic, social and political marginalization, racism, and misogyny woven into the fabric of Canadian society. The hard truth is that we live in a country whose laws and institutions perpetuate violations of fundamental rights, amounting to a genocide against Indigenous women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA people.”

For those unfamiliar with the acronym, stands for Two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex and asexual people. Its use in Canada is another legacy of the École Polytechnique massacre which has brought into the open violence against the vulnerable across society, and promoted solidarity as a way to welcome more Canadians into dialogue on violence.

These intersections came together on December 3, 2020 when Brielle Chanae Thorsen, a member of the Saddle Lake Cree Nation in Alberta, received the Order of the White Rose, an honor that includes a $30,000 scholarship. Now known as Polytechnique Montréal, the school where the tragedy occurred confers the Order each year to “a woman engineering student who wishes to enroll in graduate studies in engineering (master’s or PhD) at the institution of her choice, in Canada or elsewhere in the world.” Thorsen is the first indigenous recipient of the honor.

Zero tolerance of violence against women is a high standard, and neither Canada nor the United States has achieved it. Yet the murder of those 14 women in Montreal in 1989 continues to inspire hope and action on violence against the vulnerable in Canada and the United States.

Author

Canada Institute

The mission of the Wilson Center's Canada Institute is to raise the level of knowledge of Canada in the United States, particularly within the Washington, DC policy community. Research projects, initiatives, podcasts, and publications cover contemporary Canada, US-Canadian relations, North American political economy, and Canada's global role as it intersects with US national interests. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Securing a Digital Future for Women and Girls in MENA

Conflict in Sudan: Widespread Sexual Violence