Islamist politics have many faces in Yemen. But the tribe is still the core around which political, economic, and social lives are organized. So Islamist politics in the Arab world’s poorest country has always blended with tribal influence. For two decades, Islah, or the Yemeni Congregation for Reform, has been the largest Islamist party. It is predominantly Sunni, although tribal factors and figureheads often superseded Islam and its sheikhs in Islah. It has been a pragmatic party that has served as both the official opposition and an ally of the government.

Islam and tribe have also been a defining force in Ansarullah, or “Partisans of God.” It combined members of Houthi tribes of northwestern Yemen and Zaydi Islam, a branch of Shiism. The Houthi movement identified politically with Lebanon’s Hezbollah, although its political platform was vague and its actions often contradictory. It supported the 2011 uprising and participated in the National Dialogue in 2013 and 2014. But the Ansurallah militia moved on the capital of Sanaa in 2014 and seized the presidential palace in January 2015, forcing the president and his government to resign.

The third major Islamist force is al Qaeda of the Arabian Peninsula, a franchise that has operated out of Yemen since a Saudi crackdown forced it from the neighboring kingdom in 2004. It has been linked with a series of attacks, including the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole and the 2009 plot to blow up a Northwest flight from Amsterdam to Detroit. The Kouachi brothers also invoked AQAP in the 2015 attack on Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris. By 2015, the Sunni extremist movement had a presence in at least three provinces in south and central Yemen. By 2015, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria was also reportedly recruiting in Yemen.

Islah: The Beginning

The roots of Islamist politics in modern Yemen date back to the 1960s with the birth of a local chapter of the Muslim Brotherhood. A second Islamist social movement emerged in the 1970s, when the country was still divided into rival halves. Muslim scholars in North Yemen, a secular autocracy with strong ties to the West, were concerned about threats from South Yemen, a Marxist and atheist state backed by the Soviet Union. The clerics, led by Sheikh Abdul Majid al Zindani, established a schooling system in the north to counter anti-Islamic movements and secular messages from the south.

Dubbed “scientific institutes,” these schools resembled the madrassas that educated the young on the basis of religious texts in Pakistan and Afghanistan. The institutes provided room, board, and badly needed education for Yemeni youth, the majority of whom were illiterate. In turn, however, the institutes indoctrinated students in Salafist teachings inspired by Wahhabism, the strict ideology imported from neighboring Saudi Arabia. The schools grew to parallel Yemen’s state education system, with summer camps and other activities to engage youth. Much as in Pakistan, many of the students educated in Zindani’s institutes eventually went to Afghanistan in the 1980s to fight the Soviet occupation.

The Islah Party was founded after the May 1990 merger of North Yemen and South Yemen. It was an amalgam that merged three strands of society: tribal forces, which were powerful in rural areas; the Muslim Brotherhood, which was strong in urban areas; and Salafi sheikhs, who ran a network of religious schools. Its political spectrum included traditionalists, pragmatic conservatives, and rigid ultraconservatives. Unlike Islamist parties elsewhere, however, Islah was effectively sponsored by the ruling General People’s Congress.

Islah has been a comparatively pragmatic Islamic party. Its political manifesto describes the group as “a popular political organization that seeks reform of all aspects of life on the basis of Islamic principles and teachings.” But the manifesto also states that policies must be “centered on the realities and events of their [people’s] experiences” as well as “appreciating the network of external and internal factors that influence the running of … [Yemen’s] affairs.”

The manifesto, which is less dogmatic than its counterparts in other countries, adds that Islah favors a “gradual approach” to achieving change. In Islah’s public rhetoric, pragmatic factors have also increasingly trumped theological considerations. Islah differs from other Islamist parties in the Arab world in its focus on individual liberty, freedom of choice, and democracy, as well as on reforms based on Islam.

But the party also does not speak with one voice on pivotal issues. More than two decades after Islah’s birth, the original strands remain distinct factions, which have often sparked serious internal debates over the party’s role, its relationship with the government, and the scope of women’s rights. The result is often ambiguous, confusing, or even conflicting policy statements.

President Saleh, who had only an elementary school education, fostered the party for his own political purposes. After working his way to power through the military, Saleh had been president of North Yemen from 1978 until 1990 and then assumed leadership of the unified Yemen as part of the deal to merge the two countries. Unification made Yemen a more powerful country, but it also widened the field of political players and opponents.

Saleh wanted a new Islamist movement to help his own party, the General People’s Congress, check the potential of new political rivals. He especially hoped that Islah’s greater theological and social legitimacy would counter the former ruling party of South Yemen, the Yemeni Socialist Party.

To launch Islah, Saleh enlisted Zindani and Sheikh Abdullah al Ahmar, chief of the northern Hashid Tribal Confederation—home of Saleh’s clan and Yemen’s largest tribal grouping. For Zindani, who brought along the Salafi network, the new party provided validation and a mainstream voice. For Ahmar, Islah provided an institutional perch from which he could exert formal power to complement the respected but unofficial role accorded a tribal elder. Ahmar brought along other tribal and business associates to widen the party base.

The Muslim Brotherhood, which lacked any other political vehicle, became the third and largest strand to join Islah. Islah provided a comfortable home for the Brotherhood, even though the Muslim Brothers differed significantly from both Zindani and Ahmar. The Brothers were not Zindani acolytes, nor did they share his ultraconservative Wahhabi leanings. And the Brothers did not have steadfast tribal allegiances to Ahmar.

So from the outset, Islah was a diverse coalition of teachers, preachers, businessmen, and tribesmen with distinct and sometimes conflicting goals. Yet together these disparate strands of society partnered with the technocratic General People’s Congress to rule Yemen from 1990 to 1997. In its first run for office in 1993, Islah won 62 of the 301 seats in parliament, and in 1997, it won 57 seats. After both elections, Ahmar was selected as speaker of parliament. Between 1997 and 2011, Islah fluctuated between functioning as the largest opposition party and cooperating with the government to influence policy decisions; sometimes the party did both at the same time.

In Opposition

During its first seven years, Islah was dominated by its tribal and Salafi factions. But in 1996, during a party conference, the Muslim Brotherhood faction won control of the general secretariat. Four men aligned with the Brotherhood rose to the top: Mohammed Abdullah Yadoumi, Islah’s secretary-general; Mohammed al Saadi and Abdulwahab al Anisi, his assistants; and Mohammed al Qahtan, who headed the Executive Council. The Brotherhood-oriented leaders quietly built the backbone of the party, happy to benefit from Ahmar’s patronage but not acquiescing to the tribal scions.

The rise of the Brothers began the party’s drift away from cooperation with the ruling General People’s Congress. In 1997, Islah formally joined the opposition.

Ever the tribal chief, however, Ahmar kept his ceremonial post as speaker of parliament and his personal ties to Yemen’s president. A local analyst described Islah as “developing the body of an opposition party with its head in the governing party,” as Ahmar cooperated with Saleh while the rank-and-file membership increasingly looked like a Muslim Brotherhood political party.

The growing split inside Islah was evident during Yemen’s first direct election for president in 1999. The original party founders—tribal leader Ahmar and Zindani, the Salafist—still supported Saleh, while key Brotherhood members rejected the traditionally cozy relationship. The Brothers calculated, however, that Saleh’s election was a forgone conclusion. They opted instead to wait for a battle they might win—and began talking with other opposition parties.

The showdown played out in 2001 local elections as Islah competed openly against the ruling party, forgoing the usual negotiations over a guaranteed share of seats. In a seemingly odd pairing of Islamists and Marxists, the Brotherhood wing of Islah also launched quiet negotiations with the Yemeni Socialist Party.

The talks reflected the Islamist party’s sense of realpolitik. Whatever its commitment to promoting Muslim values, Islah was willing to negotiate quite practically with parties antithetical to its own political doctrine. As a predominantly northern party, Islah also demonstrated willingness to work with a group from the south in the name of sheer political power.

Islah’s initiative came at a political crossroads for the socialist movement, which was clearly in decline. The Yemeni Socialist Party and smaller leftist parties had boycotted the 1997 elections; by 2000, they faced political oblivion. President Saleh accused them of backing violent secession. He embarked on a campaign to deprive the socialist party of funding and confiscated many buildings it had controlled while ruling South Yemen.

Yet the Yemeni Socialist Party still had a powerful moral claim to be the voice of the south. It was also the most significant secular, leftist political faction in the country of 24 million people. The president’s heavy-handed repression resonated with Islah leaders, who empathized with an underdog.

The avowedly secular socialists and the Islamists found common ground in demanding more freedom of speech and association and in arguing for better elections. In 2003, they began a unique political venture. With three other smaller players, they formed the Joint Meeting Parties on the premise that together they could defeat the ruling party. In 2006, the coalition fielded a joint candidate—a socialist—for president. Faisal bin Shamlan won 25 percent of the vote, a respectable outcome against the long-established and better-financed ruling party.

Islah also became increasingly pragmatic on issues, pushing back against ultraconservative measures. Its legislative priorities usually involved secular topics—electoral laws, economic policies or budget issues, parliamentary oversight, and constitutional questions about the distribution of local and regional power. It accepted the separation of mosque and state, rejecting an Islamic state or theocratic rule by religious sheikhs even as it promoted religious values based on Islamic law in politics.

But the Islamist party proposed few new laws on religious issues. Fewer than half of the questions formally addressed to the government by its members of parliament dealt with Islamic practices or traditions, such as banning alcohol. Islah’s tangible achievements were still largely linked to in the social services where the party had started—religious education, welfare, and health care.

The Unraveling

Two major turning points have thrust the Sunni party into a more independent and powerful position. The first was the death of tribal leader Abdullah al Ahmar, one of Yemen’s most powerful politicians and a cofounder of Islah. His passing in 2007 diminished the tribal hold over the Islamist party. The second turning point was the 2011 uprising, when Islah emerged as a major power broker in the deal for Saleh’s resignation and the transfer of power.

The death of Ahmar, “the sheikh of sheikhs,” in 2007 started Yemen’s long descent into political gridlock. For almost a generation, he had been the political glue that had held together Islah’s divided factions and propped up President Saleh. Ahmar’s power always shaded the Islamist movement with a tribal character.

As paramount tribal leader, Ahmar had special standing, with more natural authority than a modern president. He was also chairman of Islah and speaker of parliament. All three titles effectively made him the second most powerful politician in Yemen. Only Saleh rivaled Ahmar’s political authority. Indeed, because the state’s actions often reflected tribal preferences, Saleh had to seek the sheikh’s concurrence on any major endeavor. Saleh also did not dare directly confront Islah while the grand sheikh was alive. The president needed Ahmar’s continued support when other Islah factions opposed him.

Ahmar, who reflected the contradictions at the heart of Islah, could also mediate among the party’s religious and tribal factions. He often held together the delicate political truce through his status, authority, and force of personality. Despite their growing numbers, the Salafis were held at bay by Ahmar’s reputation—and his private tribal army. And Islah’s technocrats, who were aligned with the Brotherhood, were more interested in a disciplined modern party vying for power than in the medieval tribal machinations. But they too often deferred to Ahmar.

After Ahmar’s death, Islah and other opposition groups in the Joint Meeting Parties grew bolder. In 2009, they formulated a “national salvation” plan to thwart the president and his ruling party. Islah then launched grassroots meetings countrywide to sell it. The party also called for a delay in the 2009 parliamentary elections. Its goal was to force the government to rewrite election laws and force Saleh to abide by term limits agreed to in 2006, which would have seen his rule end by 2012.

Saleh agreed to political reforms but asked that the parliamentary election be delayed from 2009 until 2011. Islah agreed, although it refused any further cooperation in an attempt to freeze Yemeni political life and weaken the president. Saleh countered with a campaign to vilify Yemen’s political opposition parties as radicals.

Islah’s political challenge coincided with two formidable security confrontations. The president also faced a rebellion in the north by the Shiite Houthi clan and an autonomy movement in former South Yemen that became known as the Hirak. Saleh began describing the Houthis as “Iranians,” members of the Hirak as “secessionists,” and Islah as “al Qaeda.” He tried to portray himself as a comparative moderate and the stable alternative.

The Uprising

In January 2011, powerful shock waves from the uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya reverberated into Yemen. Students organized mass demonstrations in University Square, which was soon dubbed “Change Square.” The flashpoints were originally economic hardships, social injustice, and a constitutional amendment that could have extended Saleh’s presidency. The central demand soon grew to include Saleh’s ouster after more than three decades in power.

As with Islamist movements elsewhere, Islah leaders were slow to recognize the protests and reluctant to participate in Yemen’s version of the Arab awakening. And when they did get involved, the party preferred to offer Saleh a negotiated exit rather than support the kind of coup that had toppled the leaders of Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya.

As pressure from the streets intensified, Islah Secretary-General Yadoumi began negotiating with the president and his allies to avoid violence. Saleh stalled. His government increasingly deployed force against the demonstrators. On March 18, at least fifty protesters were killed, a turning point that changed the character of protests and participants. A senior general responded by defecting to the opposition with his entire brigade. The addition of troops to the opposition encouraged a wider swath of the population—including many Islah adherents who had previously stayed home—to join the crowd.

As the crisis deepened and the death toll rose in cities across Yemen, Islah helped form a “committee of three” with members from the Yemeni Socialist Party and the ruling General People’s Congress. For months, they sought to facilitate Saleh’s departure and avoid Yemen’s disintegration into a failed state. The six-nation Gulf Cooperation Council brokered the final terms. On November 23, 2011, Saleh signed a deal to end his thirty-four-year rule and hand over power to his vice president Abdrabuh Mansur Hadi. His departure opened the way for all Yemen’s opposition parties to expand their political sights.

Islah played a key role in forcing Saleh’s departure, but the party experienced a series of setbacks after the uprising. In 2012, President Hadi removed General Ali Muhsin Al Ahmar, a key Islah ally, from command of the First Armored Division. The Islah-appointed ministers in Hadi’s government failed to distinguish themselves or develop a popular following. By mid-2014, Islah fighters were embroiled in a number of skirmishes with the Shia Houthi clan the ended in a decisive defeat in Amran, the defacto Islah capital and the heartland of the Hashid tribe and Al Ahmar family. Weakened militarily and politically marginalized, Islah suffered a further setback when the head of the post-uprising government and Islah confidant, Prime Minister Mohammed Salem Bassendwah, resigned in September 2014.

Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP)

In 2012, President Hadi reinvigorated government efforts to rout al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula from its redoubts in Abyan, Shabwa and Marib. But government forces were unable to hold their gains. An increasingly restive southern secessionist movement helped create a power vacuum in areas infiltrated by Al Qaeda. Its operations grew until U.S. drone attacks and a new Yemeni military offensive began to put the group in check.

Most Yemenis viewed al Qaeda as an unwanted and outside force. But in 2013 and 2014, local sympathies were stoked again when the Sunnis of al Qaeda appeared to at least partially counterbalance the aggression of Shiite Houthis in the Ansarullah movement, which was backed by Iran. The two militias engaged in an escalating series of tit-for-tat attacks and assassinations in 2014. Conflict between the rival extremist groups continued apace.

The Rise of the Houthis

The term Houthi originally referred to a large clan that occupied part of northern Saada province. Most Houthis practiced the Zaydi sect of Shiism. Throughout most of their history, they were characterized as rural, tribal and warlike, although not fanatically religious or ideological. But by 2015, Houthis became a catch-all for an ever-broadening movement opposed to reforms championed by President Hadi and the international community.

After the assassination of Houthi patriarch Hussein al-Houthi in 2004, Yemen witnessed six conflicts—often called the Houthi Wars—that pitted the government against tribal fighters from Saada. The government military, led by General Ali Muhsin al Ahmar, was unable to defeat the Houthi fighters that repeatedly menaced the capital, Sanaa.

In 2014, a Houthi militia known as Ansarullah, or “Partisans of God” occupied Sanaa. It was not the type of Islamist political movement that emerged elsewhere in the Middle East. It had expanded beyond rural fighters to include northern Shiite Houthis and national Sunni elites troubled by the 2011 uprising and unsure that the National Dialogue Conference would protect their vested interests. It reportedly had support from Iran too. Ansarullah challenged the viability of the internationally backed reform process.

The broader Houthi movement even included members of the former president’s loyalist, apparatchiks, and Republican Guards. Saleh supported the Houthi occupation of Sanaa as a means of “reclaiming stability.” In 2014, he charged that the Arab Spring “revolutions have been merely a tool for weakening armies, spreading chaos and destroying economies.” In January 2015, under pressure from Houthi militants, President Hadi started reappointing Saleh loyalists to key positions in security ministries. But after the Houthi militia took over the presidential palace, President Hadi and his government resigned on January 22, 2015.

Yet the Houthi political program was still vague and sometimes contradictory. Its Hezbollah-like denunciation of the United States and Israel often seemed largely for show. The Houthis participated in the National Dialogue Conference (NDC) between 2013 and 2014. And they did not denounce the final reform agenda. The original Houthi movement of Zaydi Shiites wanted to imitate the model created by Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and Lebanon’s Hezbollah—to have power without actually ruling. But the Houthi connection to former President Saleh, his cronies and their Republican Guard allies dulled the Houthis’ puritan image. The ties threatened to expose them as just another group sharing in the spoils of corruption.

Key Positions

Democracy

In Islah’s official documents, religion is the backdrop, not the core, of a philosophy that often resembles classical liberalism more than theocracy. Its manifesto identifies seven basic principles: Islam as a belief and a life-governing law; justice; liberty; equality; shura (consultation) and democracy; a republican system; and republican unity.

Liberty, as described by Islah, is a “natural characteristic of man,” who is “able to choose whatever desired of opinions and activities.” Democracy means “participation in government and the people’s right to decide on their affairs and choose their rulers, monitoring them and making them accountable and ensuring their adherence in the decisions they make.” Shura is “to take the opinion of the people directly or through their representatives, so that no individual or one party monopolizes the state to the exclusion of others.”

On democracy, Islah sometimes sounds more like Thomas Paine than Thomas Hobbes. Islamic law and Sharia, while invoked throughout the manifesto, are quickly qualified by references to democracy. “Peaceful rotation of authority is the essence of shura and democracy and the best process for overcoming conflict over authority—on all levels,” intone the writers. Another plank says, “Sound political nurturing of members of society to grow accepting the results of elections and peaceful transfer of power.”

Women’s Rights

In its party constitution, Islah calls for measures to “rectify the inferior image of women” and to reform the “traditional” role of women, making them partners in all societal roles. In practice, however, its progressive-sounding policies have not been internalized by the grassroots. Many, if not most, male Islah members support a traditional housebound role for women.

“Good values and morals” in the family are described as a cornerstone of social cohesion, according to the party commands. Women should give priority to “their families by better upbringing of their children.” Women are expected to “shoulder other family responsibilities, such as increasing the family income when needed.”

Islah members have also voted differently on legislation. In 2009, the government proposed raising the minimum age of marriage for women from fifteen years to seventeen years, part of the effort to reform family law. Some Islah members voted for the amendment, while others claimed it contradicted Sharia.

Yet Islah has an exceptionally strong women’s committee that takes a leading role in organizing its election activities, even though it is a conservative religious party. Women’s leadership within the party is also strong. Tawakol Karman, the 2011 Nobel Peace Prize winner, is an elected member of Islah’s Shura Council. Other prominent women leaders include Dr. Amat Al Salam Raja, who won more votes than Zindani when she ran for Islah’s Shura Council.

During elections, small bands of Islah women, recognizable by armbands worn on the sleeves of their abayas, are often out canvassing voters, delivering leaflets, and convincing reluctant voters to go to the polls on election day. According to postelection surveys, Islah’s efforts to court women have paid off.

Israel

Israel and Zionism get only passing references in Islah literature. In the preamble to Islah’s manifesto, “Zionist endeavors” are described as one of the causes of “civilizational conflict,” but Israel and the Palestinians are never specifically mentioned.

A shorter Islah election document in 2003 mentions “supporting the Palestinian’s jihad and legitimate struggle against the Zionist occupation,” but Islah has never shown any inclination to join causes or struggles outside Yemen’s border except in symbolic fashion. Islah has never pursued special links to Hamas or any other organization with a terrorist designation.

The Future

In 2012, Islah again joined the governing coalition in Yemen, pledging to stay until the transitional period ended. But power in Yemen is often more of a curse than a blessing. Islah’s political hand was weakened as the government came under attack by the Houthis and was unable to provide effective governance under Hadi’s weakened rule.

As part of the government, Islah faces a chronically weak economy further damaged by years of conflict. Water and resource shortages threaten large population centers. And a series of intractable tribal conflicts have inhibited foreign investment, damaged critical infrastructure, and stunted social development.

Yet Islah is part of a wide-ranging coalition that includes southern moderates, tribal leaders, and technocrats and it is likely to survive in one form or another – even as its tribal wing battles the Houthis. To stabilize Yemen, the transition government’s top domestic priority will be trying to convince the Houthis and the more radical members of the Hirak to join efforts to rebuild Yemen. The transition government will also need foreign aid or investment to prevent the Arab world’s poorest country from becoming a failed state.

In early 2015, the Houthi presence in Sanaa brought relative quiet until the group chose to attack the presidential palace and place further demands on President Hadi for more power-sharing. He was ultimately forced to resign. Opposition to the Houthis was not sufficient to dislodge the militia. In the meantime, the National Dialogue political goals--supported by the Gulf countries and the outside world--were left unaddressed. The Houthis will have to decide whether or not to participate in politics or continue to menace the country with military force. The odd alliance of Saleh cronies and Ansarullah could fray if a political process regained momentum.

AQAP may gain from the conflict between the Houthis and Islah, with government attention and resources increasingly aimed at minimal stability and even just survival. Yet the Houthis present an existential threat to Al Qaeda, since the Shiite group represents a home-grown, well-resourced and effective fighting force motivated to battle the Sunni extremists they consider both foreign and apostate.

Leslie Campbell is senior associate at the National Democratic Institute and regional director for the Middle East and North Africa. Since 2009, Campbell has made a number of trips to Yemen to discuss issues of political reform and dialogue among political factions as an alternative to conflict.

Photo credit: Islah logo via Wikimedia Commons; Abdrabuh Mansur Hadi by U.S. Department of State via Flickr Commons (cropped)

The following is a link to an NPR program on the war in Yemen as of April 2015.

The Islamists

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

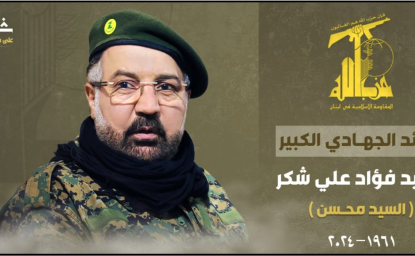

Israel Targets Hezbollah & Hamas Officials

The Life and Death of Ismail Haniyeh

Houthi Leaders & Goals