The transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Nina Rozhanovskaya: From the Kennan Institute, this is Nina Rozhanovskaya, and you’re listening to The Russia File. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has highlighted some of the Russian domestic problems and uncomfortable realities that used to receive less public attention than they deserve. One of them is the uneven economic development of Russian regions and the fact that for many people, the army is the only social lift, and seemingly the only way to break away from poverty. And another is the undercurrent of ethnic tension in a country that always proudly states that it is multinational and religiously pluralistic.

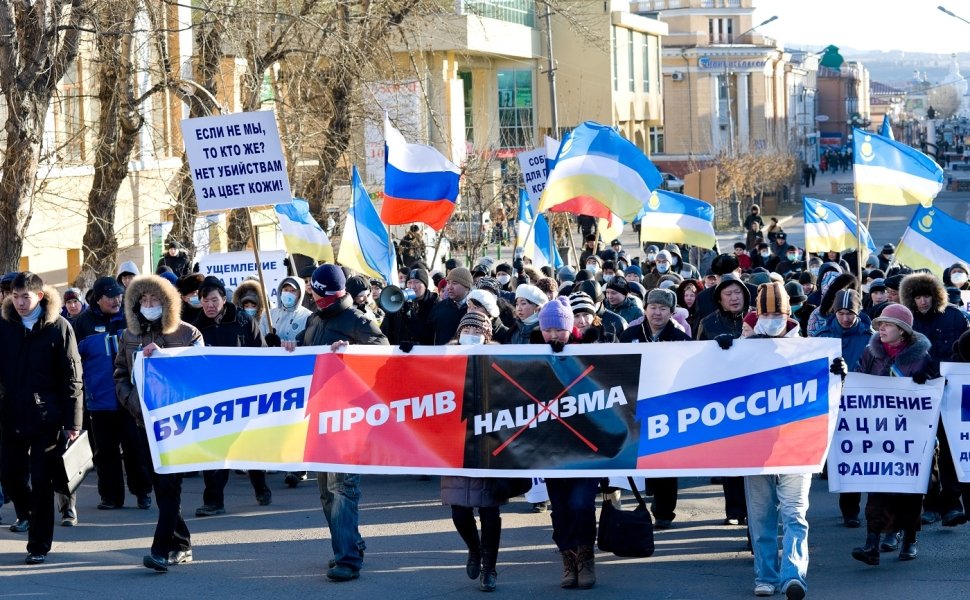

Today, we will specifically focus on the experience of the Buryats, an ethnic group of Mongolic descent, and the Republic of Buryatia, a Siberian region, which has been under the spotlight since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, because of the Buryats’ seemingly disproportionate representation among the Russian forces. For that conversation, my guest is Maria Vyushkova, a Buryat activist and research scientist. Maria, welcome to the program.

Maria Vyushkova: Hello, Nina. Thank you for inviting me to your podcast.

NR: I look forward to our conversation. And let us start by providing some background. Would you be so kind as to tell our audience a little bit about Buryatia?

MV: Buryatia is a part of the eastern Siberian region. Some researchers believe that Siberia is actually a colonial term, so some researchers prefer to say North Asia. Nevertheless, Buryatia is the region to the south of Lake Baikal and historically it was a much greater area. But after Joseph Stalin’s partition of Buryat-Mongolia, which was the old historic name of our region, it was divided into five parts. That happened in the 1930s, and the prominent anthropologist and expert on indigenous peoples of Siberia, Professor Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer, described this very aptly as Stalin’s gerrymandering of Buryatia. So the goal of this partition was to divide and dilute Buryats both politically and demographically, to prevent them from forming their own political nation. And, unfortunately, he succeeded. So right now, Buryatia is much smaller than it initially was, and the majority of the population of Buryatia are ethnic Russians, so Buryats now are a minority in their home region.

NR: And if I understand correctly, not only they are a minority in their own region, but a lot of them ended up in different regions of Russia.

MV: Yes, the family of my great grandfathers ended up outside their homeland as a result of Stalin’s partition of Buryat-Mongolia. They ended up in the Irkutsk region of the Russian Federation, and we are now called Irkutsk Buryats. Right now, Buryats mostly live in three regions of Russia: the Republic of Buryatia itself, Transbaikalia or Zabaikalsky Krai, and the Irkutsk region. I think that this division had some cultural and economic consequences. And it is also reflected in how ethnic Buryats from different regions were affected by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

NR: And before we move to this topic, I would like to confirm for the listeners: so this ethnic group, despite its traumatic history, it still does have its own language and its own distinct culture, doesn’t it?

MV: Yes, that’s right. However, unfortunately, very few Buryats still speak their own language. Most of us use Russian, and the usage of Buryat language is limited to some mundane everyday domestic matters because we don’t speak about politics or science in the Buryat language. And because of that, our language lacks the proper words or terms for political events or for some parts of social life which are important now in the 21st century. And as activists, when we tried to write antiwar texts in Buryat language, we had difficulty with that, because unfortunately, our language lacks some specific terms, and we had to use Russian words instead.

It is officially considered to be an endangered language, which is likely to totally disappear. When I was a kid, we still had Buryat language lessons at school, but right now it’s no longer mandatory in schools of Buryatia, and therefore people mostly choose to exclude it, to make life easier for kids, because if it’s not required, you have a lot of other subjects to study, so it’s only natural for people to just say, “no, we don’t need it.” And that’s a problem. Because in my case, though I don’t speak my native language, I am able to understand. And also, I learned a lot of our Buryat culture and history from those lessons.

For instance, we talked about 19th century history, the 19th century and earlier. We even touched, to a certain degree, on the issue of the colonization of Buryatia by the Russian Empire. And also we talked about Stalin’s Great Purge in Buryatia and those Buryats who were imprisoned, sent to Gulag labor camps, or killed. And right now, unfortunately, kids will be deprived of this, just because the Buryat language is no longer mandatory at schools. And I think it was a very wrong decision.

NR: I guess it is very easy for ethnic Russians to forget that in addition to all the traumatic events that every citizen of the Soviet Union had to experience in the 20th century, indigenous nations and ethnic minorities have the additional trauma associated with the disappearance of their languages and their culture.

MV: And colonization initially. It started in the 17th century, when the first Russian settlers arrived, and it continued into the 18th century. But of course, it wasn’t a peaceful and voluntary unification, as it is described in official history books in Russia. Of course not; it was a military conquest. But this issue is still not talked about, and moreover, in present-day Buryatia, you will be persecuted if you talk about this openly and publicly.

NR: Is that because the idea of ethnic groups or regions, even in theory, wanting to split from Russia proper is now completely outlawed?

MV: Yes, and also there is a law against hate speech in Russia, which is interpreted in very bizarre ways. So it’s officially called the law against inciting hatred, but in reality, it’s used for political persecution, very widely. And, as far as I know, some people were taken to court and tried, because they spoke out about the colonization of Buryatia.

NR: As I understand, it was partly your personal background that prompted you to engage in activism after the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. And you are one of the co-founders of the Free Buryatia Foundation. So what is the mission of this NGO? What is this work about?

MV: This work is, first of all, about antiwar activity. It’s about telling people the truth about this war and telling Buryats living in Buryatia that they should not participate in this war. This is, of course, the most important part. Then it’s about promoting pro-democracy views in Buryatia and promoting the values of freedom and democracy. And also it’s about educating the outside world about Buryats, because there are a lot of misconceptions about our nation, a lot of myths and a lot of misinformation, unfortunately. And it is spread by all sides in this situation.

For instance, if you remember the infamous interview of the head of the Catholic Church, Pope Francis, about one year ago—I think it was November 2022—where he said that Russians are not to blame for the war crimes in Ukraine, because the worst atrocities, of course, they were committed by ethnic Buryats and Chechens who “are not of Russian tradition.” And unfortunately, this type of misinformation was spread by very prominent figures in the West.

NR: And I guess, as it often happens, the apologies issued afterwards and clarifications are read by fewer people than the initial statements. We’ll get to those myths and misconceptions in a moment. But first, from what I understand, your research has revealed that Buryats are disproportionately affected by mobilization and also by disproportionate losses among those drafted to fight in this war. Could you expand a bit on that? What are the figures? How did you come to that? And what are the reasons for that trend?

MV: This research paper I published, it was based on the obituaries or social media posts by the relatives of the deceased. And, for instance, there is a volunteer group in Russia who collect the obituaries published in both local media and Russian-language social networks. They are well known because they collaborate with BBC News Russian and Mediazona, the independent Russian news outlet. They publish their reports every two weeks and I also collaborate with them. And I collected the data independently from ethnic or regional activist groups from different ethnic regions of Russia, and they keep their own lists of casualties based on either social media posts—including posts in their native languages, for instance, in Tuvan language in Tuva—and also based on the reports from relatives who sometimes contact them directly and tell them: our relative died in this war.

I combine all this information and I use it to analyze the ethnic composition of the confirmed Russian losses. It is only a tip of the iceberg, because there are still many casualties which are not reported. And we don’t know what the exact number of these unknown casualties is. But nevertheless, we found out that the indigenous peoples of Siberia, the ethnic minorities, are very significantly overrepresented among Russian-side casualties, and specifically the Asian ethnic groups such as Kazakhs, Buryats, and Tuvans. These three groups were most significantly overrepresented. And also the so-called of the North and Far East. They were also very significantly overrepresented.

So there were huge ethnic disproportions, and as of September–October last year, as far as I can remember, it was seven times higher death toll per capita for ethnic Buryats compared to an average Russian citizen, and ten times greater per capita death toll for ethnic Tuvans, and I think about seven times for ethnic Kazakhs, as well.

NR: That means that even [though] those groups are not exactly very numerous when it comes to the overall Russian population, a lot more of them get drafted into the army and then more of them die. So why do so many people of this background end up in the army fighting in Ukraine?

MV: It’s a very complex phenomenon. There is no simple explanation for this, because it’s not correct to say that it’s because, for instance, ethnic Buryats end up serving in the military more often than Russians. No, that’s not the case, because they don’t serve in the military seven times more often than Russians. No, that’s not true. In reality, there are very complex reasons for that.

Of course, there is some disproportion in the ethnic composition of the Russian army itself, yes. Just because Buryatia has one of the highest concentrations of military units or military bases in the region per capita, because it’s a very sparsely populated region. There are less than one million people there, but a lot of military bases and the economic situation is such that it is really hard to find a job in Buryatia, and especially for young men. And because of that, many of them, yes, ended up serving in the military because it was a very competitive job option for young men in Buryatia. The army, it’s a very stable employer. And also they provide housing, they provide mortgages, and they provide certain benefits which are very helpful for a young family. So before the war, it was considered a very competitive employer or job option for young men in Buryatia.

But that’s not the only reason. The most important reason for this disproportionally high death toll was, I think, the discriminatory deployment policies in the Russian army. It was because of how these specific military units in Buryatia were used. It didn’t depend on the ethnicity specifically, because most of Buryatia’s population are Russians. And actually, the Russian population of Buryatia, they also had a several times greater per capita death toll compared to the average Russian population. It wasn’t defined specifically by ethnicity, but mostly by the region. And this is the result of how those military units were used during the invasion of the Kyiv region in the very beginning of the Russian invasion of February 2022, because the fifth tank brigade from Ulan-Ude, from Buryatia, they were given a task to try to cut off the city of Kyiv from the rest of Ukraine. And basically this tank military unit, it was just not sufficient for this type of task and many of them died there.

NR: So in the end, we are dealing with a situation where if you’re a Muscovite, let’s say, or you are from St. Petersburg, you are less likely in general to be drafted into the army as part of the mobilization effort. But when you are, you are less likely to end up in a division that will be used for the most difficult tasks that are assigned to different units.

MV: Yes, they were given a suicidal task, which was impossible to fulfill. And if you look at the time distribution of the casualties from Buryatia, the highest peak will be in the first weeks of the Russian invasion. And it all happened mostly in the Kyiv region. And it is peculiar that Vladimir Putin didn’t use, let’s say, Tamanskaya diviziya or Kantemirovskaya, the elite tank units from Russia. But they use a tank unit from Buryatia for this type of a task. And they knew beforehand that many of them, probably most of them, will die there.

NR: I can see why you feel that it’s a very intentional decision. But also it does connect us to another aspect of this problem, the fact that this division was used in those very first weeks of the invasion and then atrocities committed in Bucha came to be attributed to ethnic Buryats. As far as I know, one of your missions is to try to debunk the idea of Buryats’ responsibility for the Bucha massacre. Could you please say a bit more about that?

MV: When, in early April 2022, Russian occupation army left the Kyiv region, horrendous atrocities were uncovered in the Ukrainian city of Bucha in the Kyiv region. And we know that hundreds of civilians were murdered there. And it all was blamed on ethnic Buryats, based on one publication in the Ukrainian media. Later on, other Ukrainian sources made a very thorough investigative work, and they found out that the Bucha massacre was committed by the paratroopers or air assault brigade from the Russian city of Pskov, which is in the northwest of Russia, the opposite corner of the country. And, of course, they are almost exclusively ethnic Russians.

It is now obvious from all serious Ukrainian sources, for instance, the Suspilne channel published a very good investigation on this topic. And moreover, some of those Pskov paratroopers were captured by Ukrainians later on during this war. And those captured soldiers, they are not Buryats at all; they’re not even Asian. But it was already too late and no one paid proper attention, because this story of bloodthirsty, savage Buryats killing civilians in Bucha, it has already become viral. And everyone was talking about that. And very few people ever paid attention to more thorough investigations which came out later, including the New York Times investigation.

NR: But it’s interesting that the whole thing about Buryats becoming the face of this war, it’s not entirely new. I believe the rather offensive expression, “Putin’s militant Buryats,” which sounds even worse in Russian, «боевые буряты Путина», emerged before the full-scale invasion, back when the war in the Donbas was only just beginning. So why were they singled out then and why are Buryats singled out all the time? I would assume it’s because they have Asian facial features and it’s relatively easy to differentiate between them and ethnic Russians. Is that the reason?

MV: Yes, because as we know, those same paratroopers from Pskov who are responsible for the Bucha massacre, they also took part in the Donbas war, but it was harder to distinguish them from the Donbas population. Putin was promoting the narrative that it is the population of Donbas who are fighting against Ukrainian forces, that it is internal conflict in Ukraine, and those paratroopers from Pskov, they were sent there under the guise of miners from Donbas. But it was just easier to disguise them, compared to ethnic Buryats who served in the fifth tank brigade from Ulan-Ude, which was also sent there. So it was much easier to single out the Asians there and to say they are obviously not from Donbas. They are obviously soldiers from Russia. This is how it was proved beyond any reasonable doubt that Russia sends its own soldiers to take part in the Donbas war. And unfortunately, yes, this is how Buryats became the face of this war.

And as for the “militant Buryats of Putin,” «боевые буряты Путина», it was a video on YouTube. It was recorded by some pro-Putinist youth organization, and they paid Buryat teenagers to take part in this video and to say that “we love Putin and we are militant Buryats of Putin.” And many of them were not interested in politics at all, and some of them became Putin’s opponents later on, and some of them even left the country. The president of Free Buryatia Foundation, Alexandra Garmazhapova, talked to one of them, a girl who now lives in Germany. And she is opposed to Putin now [that] she [has grown] up, because she was 16 when she participated in the recording of that video, and she said, “I was paid to say that I love Mr. Putin, and I wasn’t even interested in politics at that time.”

NR: Let’s delve a bit deeper into that, since you’ve mentioned politics. What is the general political orientation of Buryatia? And what are the political values of people there? Do people vote? Is there an active civil society?

MV: It’s interesting because before the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, I would describe Buryatia as a politically active region. And there was a significant degree of political competition compared to other regions of Russia. For instance, during the big federal election, you would never get 90 or 100 percent of votes for Putin or for Putin’s party, United Russia. There has always been a significant degree of political competition in Buryatia and also political activity, protest activity. There were very significant protests in Buryatia in 2019. I used to believe that, if properly democratic elections were held in Buryatia, Vladimir Putin wouldn’t win there. And I expected probably communists to win.

Historically, Buryatia is very much supporting the Communist Party. Some people are nostalgic for the Soviet time because during the later Soviet era, the Brezhnev era, it was to a certain extent the golden age of Buryatia. Buryats were, as prominent researcher Melissa Chakars put it, the model minority in Soviet Russia. For instance, the education level among the ethnic minorities was second only to Soviet Jews. And there are many other indications that Buryats were doing really well during that time. So many people are obviously nostalgic about the Soviet time, but some view the Communist Party as opposition to the Putinist party, United Russia. This is how it was before the full-scale invasion. But right now, the situation has changed because I think people became disappointed in the Communist Party because it aligned with United Russia, with Putin’s party, so much [that] they became indistinguishable. And that’s why the Communist Party failed miserably during the latest election, in September [last] year.

I think people just got disappointed. They just decided not to go, not to show up to the polling places. And as for the protest activity, which was very significant before this full-scale invasion as well, it was all suppressed. I did an interview on my YouTube channel with prominent Buryat political activist Nadezhda Nizovkina, and she told me that because Buryatia is such a small region and there are such strong horizontal connections between people in our region, it’s very easy to suppress any protest because you cannot just threaten that person, you can threaten their family as well. And this is why many Buryats who left Russia for political reasons, they are still scared to speak out because they’re afraid that it will hurt their relatives back in Buryatia.

NR: It sounds a bit like the situation with the Russian regions in the North Caucasus. Even people who left do not feel entirely safe, or at least they don’t want to place their families and loved ones back home in danger. So a tightly knit community like that is more vulnerable in a way.

But I also wanted to ask you: I know that today, in any Russian region, it’s difficult to find much activism and antiwar protests because of the new repressive legislation. But people in the cities and villages see men leaving for the war and coming back in coffins. Do we have a way to measure if it has an effect on the public sentiment?

MV: Well, I can tell you that, for instance, judging by the obituaries, the percentage of ethnic Buryats and people from Buryatia in general has decreased very significantly. No one is talking about that. At the very beginning of the war, in March 2022, Buryats made up to 3.5 percent of total Russian casualties, a huge number, because Buryats only make up 0.3 percent of Russia’s population and more than 3 percent of the casualties. And now it’s about 1 percent. Nevertheless, even despite the disproportionate mobilization, the percentage of ethnic Buryats among the casualties has decreased more than three times.

NR: How does that work? Could you please explain?

MV: That means that the Russian military leadership failed to replenish those military units from Buryatia, to replace those people who were killed or wounded or left the army. There are a lot of them. They just failed to recruit enough people from Buryatia to cover for those losses. That means that Buryats actually don’t want to participate in this war unless they are forced to, unless they’re forcibly mobilized. That shows that people, not just ethnic Buryats, but generally speaking, the population in Buryatia is not that enthusiastic about this war. Well, they can say all those politically charged words they are required to, but they are not enthusiastic at all about actually participating in this war.

And this shows, I think, the actual degree of support of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Those people were sent there by deception, because they’re not told where they are being sent. It was just under the guise of some sort of military training in the Republic of Belarus. And then they were deployed to the Kyiv region, which they did not expect at all. Let’s remember that. So those ethnic Buryats who died in the very beginning of the war, they did not actually join the army in order to attack Ukraine. No, they didn’t expect that.

NR: So we can’t say that there is shared anti-Ukrainian sentiment, that the people are buying into the anti-Ukrainian propaganda….

MV: Not at all. They joined the army because they wanted to feed their families and they never expected this type of invasion to break out because they expected it to be a standard 9 to 5 job.

NR: To follow up on that point about joining the army or not being willing to join the army, after Russia announced partial mobilization in September 2022, a lot of potential conscripts fled. And we know that Buryatia shares a border and some very important historical ties with Mongolia, which is located right between Russia and China. So do we know if many people from Buryatia fled for Mongolia? Do we know if they were welcome there?

MV: Yes, very much so. A very significant number of Buryat men fled to Mongolia. There were huge lines of cars at the Mongolian border when the mobilization started. We are immensely grateful to Mongolia for opening the door to these people and letting them stay, and many of them still stay there. So I think it was an event of historical scale, because this is how I think we rediscovered our identity as a Mongolic nation, which was long suppressed since Buryat-Mongolia was renamed as Buryatia during the Khrushchev time. And of course, we are immensely grateful to Mongolia for doing that. And yes, it was very significant. And some actually went to Kazakhstan as well, and a significant amount of Buryats still stay there, both in Kazakhstan and Mongolia, those people who fled mobilization.

It was a very significant exodus of ethnic Buryats, because in Buryatia, the local authorities used barbaric methods; people were pulled out of their beds at 4 o’clock in the morning and taken away. Yes, this is what happened. The problem is many people in Russia don’t know their rights. When they come with police officers and take you away, people just assumed that it is legal. But in reality, it was not. But many people didn’t know that they could refuse, that they could go into hiding and somehow avoid it. And it’s pretty obvious that remote regions and rural regions were hit disproportionately hard. And I think it was a political decision, to avoid disturbing big cities and probably central Russian regions.

NR: It is well known that discontent of Muscovites always matters more. I am saying that as a person who actually lived in Moscow for years; that’s not even something that a Muscovite can control. One of the reasons, I assume, is that when people in Moscow protest that’s much more visible to everyone in the country and overseas.

MV: Yes, and there was also, I think, a significant component of ethnic or racial discrimination involved as well, because the political decision was to target those people who, let’s say, the Muscovites don’t associate themselves with. And ethnic minorities perfectly correspond to this description. And also not just Russia’s indigenous ethnic minorities, but also recent immigrants. It’s almost official right now that naturalized immigrants from the Central Asian states are targeted in the first place. And I think it’s pretty obvious that it's not just regional. It’s specifically ethnic discrimination.

NR: Would it be fair to say that while we are focusing, indeed, today on the Buryat experience, it is quite representative of the experience of different ethnic minorities in Russia when it comes to relations with the state, systemic racism, discrimination? Would that be correct?

MV: Yes, absolutely, of course. For instance, during our interview with [indigenous rights activist] Pavel Sulyandziga yesterday, he mentioned that the ethnic villages of small-numbered indigenous peoples of the north were hit disproportionately hard. In some cases, they took away or at least attempted to take away 100 percent of the male population of [eligible] age.

NR: And we are talking about truly small nations. There are around 460 thousand Buryats living in Russia, a significant number, and their language and culture are still vulnerable for historical reasons. And with those small nations and ethnic groups of the Russian north, we are talking about thousands and sometimes even hundreds of people. Some of those cultures are on the brink of extinction as it is.

MV: For instance, in one Nanai village, they tried to take away 100 percent of the male population of [eligible] age. Also [Sulyandziga] mentioned the Udege village, where 30 percent were taken away, 30 percent of adult men of that village. And also an activist from Sakha-Yakutia Republic mentioned a Chukchi village where I think it was up to one-third. So it was disastrous. And I think they specifically targeted the small-numbered indigenous nations because no one cares about them in Russia. That’s the reason. It was politically safe to target ethnic minorities, because of the degree of xenophobia in Russia and also because of how remote those regions and those specific settlements are.

Or, for instance, with naturalized immigrants, they just tried to pit public opinion against them, like, “they got the citizenship of our great country, but they don’t want to fulfill their duties towards our country, so let’s take them away and send them to the front lines.” This is what they’re trying to do right now, unfortunately. And I think it’s obvious that it’s not regional. There is also an ethnic discrimination component; it’s not just regional discrimination.

NR: You’ve mentioned that Buryats are rediscovering their sense of identity now, partly because of the help they have received from Mongolia as a friendly nation, partly for other reasons, including the war itself. So do people find solace in traditional culture? Are they keen to learn the language? What trends do you see in that regard?

MV: Yes, that’s a very interesting question. Yes, of course there was a significant rise in interest in traditional culture, in the language, etc., but unfortunately, it’s also exploited by Putin's propaganda. They tried to exploit the traditional culture of ethnic minorities in order to address them with propaganda, especially within the Republic of Buryatia. They try to appeal to or to tailor militarist propaganda to a specific audience, especially within ethnic regions, not just in Buryatia. And one of the Sakha people who fled mobilization, the Sakha-Yakut people, told me that when the full-scale Russian invasion in Ukraine started—and he was living in Moscow at the time—but when he went back to Yakutsk, he noticed that there was a lot more visual propaganda in Yakutsk compared to Moscow. That’s also very interesting. Even the propaganda machine is targeting mostly remote regions like Buryatia or Yakutia and not Moscow. Though obviously the decision to start this full-scale invasion was made in Moscow and not in Buryatia or Yakutia. And it is obvious that it is the Kremlin who wants to occupy Ukraine and not Buryatia or Yakutia.

And all those events led to the revival of a Buryatia independence movement. I think to a certain extent it stems from despair, because so much misinformation is spread by prominent Russian opposition figures about Buryats. And ethnic Buryat activists, they cannot associate themselves with the Russian opposition as well, because the antiwar leaders, they’re blaming ethnic Buryats for all war crimes in Ukraine. And because of that, they often think: probably we should find our own path in this world, because we can associate ourselves neither with Putin’s Russia nor the new democratic Russia, which the opposition leaders promise us. Probably we should aim at independence of our region. And I think the interest towards the Buryatia independence movement has grown very significantly as well.

NR: That’s very interesting, because that means that even in the shared space of activism and protest, there is a split among different groups of antiwar Russians, when it comes to defining their own destinies. When you consider, even just in theory, an independent Burytia, is there a specific scenario at this stage?

MV: There are different views on this subject, but I haven’t yet seen some sort of elaborate project of independent Buryatia. It’s mostly like a sentiment. We feel betrayed by both sides within Russia, both by Putin’s Russia and by the anti-Putin antiwar opposition leaders who nevertheless want to shift the responsibility from Russians to ethnic minorities for the atrocities committed by the Russian army in Ukraine. At this time, I think it’s, to a very significant extent, an emotional thing. And I totally understand that because I share, to a certain extent, those feelings, too, because it does hurt a lot. I even titled my recent talk at a conference…it was the Global Solidarity lecture series organized by Stony Brook University, and I entitled it “Buryats and the Russian Invasion of Ukraine: Misplaced Loyalty and Double Betrayal.” So we feel betrayed by both sides.

NR: That is, by the Russian leadership, the regime, and the Russian opposition.

MV: Yes, exactly. And in this situation, we don’t have a side we could join.

NR: I have one more question about your organization, because the work that you do is extremely important. But the Free Buryatia Foundation was already labeled both a foreign agent and an undesirable organization by the Russian Ministry of Justice. And people who understand the system know that it creates legal repercussions both for your team, but also for any Russian citizen who comes into contact with you and with what you do. So how did these labels affect your work? Do you still succeed in reaching the people in Buryatia despite these new obstacles?

MV: First of all, I need to clarify that I’m not a part of the Free Buryatia Foundation anymore. Right now I’m working on my own. But speaking about the Free Buryatia Foundation, I strongly believe that all those labels—as a foreign agent, as an undesirable organization—they were used in order to prevent people from contacting the Free Buryatia Foundation, from trusting them. I think that was the main goal of the Russian authorities in doing that, and I think it’s because public opinion is changing, towards disapproving this war and specifically in Buryatia.

And I think those labels are recognition of the efficiency of such organizations, because the Russian authorities, even on the federal level, recognize the Free Buryatia Foundation as a significant threat to their propaganda effort. And they want to prevent not just ethnic Buryats, but in general the population of Buryatia from believing what the Free Buryatia Foundation says. They have become prominent, well known, both in Buryatia and outside, and I think in a certain way it’s like a token of recognition of their work. Right now, such labels as undesirable organization, they make people curious rather than afraid, because everyone knows that it is people who tell the truth who get those labels. But apparently, yes, it’s an attempt to prevent people from listening to antiwar activists.

NR: And my final question: even though you are not part of the Free Buryatia Foundation anymore, you are one of the co-founders, and the implication of the name of this organization is that Buryatia, just like Russia, is not currently free. So I was wondering: for you, what does that freedom that you are aiming for look like? What is your personal vision of the future for Buryatia? In some, I don’t know, ideal future reality.

MV: First of all, I want this war to end. I want the Russian army to leave Ukrainian territory, including Crimea, of course, and the borders of Ukraine to be restored. And I want Buryatia to be democratic. And I have no specific opinion on whether or not it should be independent or be a part of Russia. I think it’s for the people of Buryatia who actually live there, it’s for them to decide it. And I want them to have this right, to make this decision. And also I want people to be free to elect their own leadership and to decide how to use the natural resources on their land, and for their civil rights to be respected. I just want a normal future of which we won’t be ashamed. And that’s probably it.

NR: I certainly hope that it happens sooner rather than later. And I do wish you all the best in your mission to educate people about your country and your region, and in raising awareness about all the problems related to ethnic tension in Russia and to the war in Ukraine. Maria, thank you very much for joining me today for this conversation.

MV: Thank you for having me.

NR: From the Kennan Institute, this was Nina Rozhanovskaya. Thank you for listening, and we look forward to having you with us on the next episode of The Russia File.