The transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

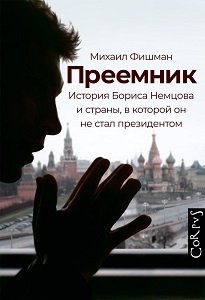

Izabella Tabarovsky: Hello and welcome to The Russia File. I'm Izabella Tabarovsky. And today we're continuing our conversation with Misha Fishman about his book, The Successor: The Story of Boris Nemtsov and the Country Where He Didn’t Become President. You can find a link to the first part of our conversation in this episode's show notes. Misha, welcome to the program.

Mikhail Fishman: Hi, thank you for having me again.

Izabella Tabarovsky: Last time we talked about Nemtsov's rise from a local politician to one of Russia's most popular political figures; we talked about why Boris Yeltsin found himself drawn to Nemtsov; we talked about the Chechen war, which presents so many parallels with the war in Ukraine today. Today, I want us to start by talking about the rise of President Putin and Nemtsov's relationship with him.

The last time we stopped, essentially Yeltsin convinces Nemtsov to come to Moscow in the role of first [deputy] prime minister in 1997. But Nemtsov's fortunes start to change, rapidly and radically. And at some point, Vladimir Putin comes [up] on Yeltsin's radar. And it's hard to remember this today, but initially Putin was quite pro-democracy and pro-free press, and quite liberal, it seemed. And the liberals around Yeltsin supported him. What about Nemtsov?

Mikhail Fishman: It would look as if initially Putin was pro-democracy and pro-free press. At least that's what he said. At least that's what his statements were. But in fact, he was basically in late ‘90s responding in a way that would look natural to any official across Russia's bureaucracy. That was basically it. In fact, it became very visible during his presidential campaign that he is more of a clean slate. Nobody knows what his actual platform will be when he becomes president. And pollsters would remind you that the Russians didn't know what to expect from Putin when he will become president.

What also was important is that he was Yeltsin's successor and Yeltsin's choice, but he looked very different from Yeltsin and he somehow managed to focus on[to] himself very different hopes and aspirations and, controversially, different hopes and aspirations. Liberals would expect from him that he would keep Yeltsin's government reforms and pro-Western type of policies, and nationalists would expect something very different. Somehow, he assembled all the hopes and all the aspirations of the nation back then.

But when we get back to Nemtsov, we know that, yes, he was, of course, shocked with this choice of Yeltsin, not simply because [Putin] was from [the] KGB, but because he was basically unknown—he was just a clerk from the government—and the vast majority of [the] Russian nation simply didn't know how he looked. That's what was the most shocking in Yeltsin's [choice] of Putin as his successor. But [Nemtsov] supported [Putin]. He supported him as part of [the] Union of Right Forces. He was one of the leaders of this liberal bloc. And on a personal level, he supported Putin's idea of fighting oligarchs because that was Nemtsov’s own platform for so many years before that.

And later it would become clear that Putin would see something very different from what Nemtsov would mean to fight oligarchs. But nevertheless, back then he supported this idea.…For example, in very early January 2000, when it's already clear that Putin would win the presidential election in a couple of months, [Nemtsov] writes in the New York Times that—and it's a quote—"Putin is Russia's best bet.” Yes, he's new. He's [a] clean slate in a way, but he is the best choice Russia can get because he doesn't bear this responsibility for the ‘90s and he can take it from here and move forward, towards [a] more democratic, more civilized, more economically reformed, rule-of-law type of Russia; [those were] his words, that was his opinion column in the New York Times back then.

Izabella Tabarovsky: What's interesting is that you discuss in the book how basically at this point,…there is still an election campaign going on and everybody knows that Putin is going to win anyway. But what's clear, what shows clearly that the times are changing, is that an opinion poll was run to consider who Russians might want to see as president and…they're given a bunch of historical figures to choose from—historical and fictional figures. So, the figure that gains the most points is Stierlitz, who is a famous fictional intelligence officer from a very popular Soviet TV series. So in a way, this is what people wanted and this is what people got. Do you see some kind of a correlation there?

Mikhail Fishman: Yes, absolutely. We have to understand that Yeltsin, his government, and his reformers got unlucky in 1998 when Russia defaulted on its debt and got into a huge economic crisis. And that was not only [an] economic default, but also [a] political one. That's when the Russian nation realized that [the] ‘90s are over, that [the] ‘90s are these dark times. And then this frustration starts really growing and what can be made about this frustration is [the] rel[iance] on some idea of strength and force, which was lacking in the nation’s mind in the ‘90s. That's where the idea of Stierlitz comes from.

And that was obvious to pollsters back then, that the new president should have this background, either special forces or military or something like that, but something that would project the idea of strength and force, [that] Russians as a nation would defend themselves from the chaos in which they found themselves.

Izabella Tabarovsky: You talk about how that first campaign—and really the only real campaign that Putin participated in—shaped his understanding of just how powerful television is, because Yeltsin's team threw all the resources they had into making sure that the media presented the right image of Putin and also at the same time denigrated his opponents. So how did that experience shape Putin's relationship with the media? Because this is a really important question, given what's happening now and the extent to which independent media is suppressed. Do you see the roots of that perhaps back then?

Mikhail Fishman: It was absolutely crucial. And it not only shapes Putin's relationship with the press, but also his idea of what politics is or how he rules Russia and how he builds his aggression against the world. But the truth is that in August 1999, when Putin was appointed as prime minister, only every fourth Russian actually knew his name. He was a nobody. He was virtually, literally, no one. He didn't have any kind of political background, nothing. That was so strange for the country, which actually had [an] open and very competitive political landscape during [the] years before that. And in a short span of three months, he becomes number one, he becomes absolutely popular and the projected winner of the presidential election, and Primakov and Luzhkov wouldn't even take part in the presidential election, because they understand in December that the game is over.

So in three months, he makes this transformation from nobody to a national leader. And that's television’s work. That's when he realizes the power of television, of media. That's when he realizes that to happily rule from there, he has to have it under control. And his first move as president, the next day, after he is inaugurated as president in May 2000, is his attack on [the] independent television channel NTV, which was controlled by Vladimir Gusinsky back then and was supporting Luzhkov and Primakov. And that's when he makes his first move. It would last for a year, even longer—the takeover of NTV. But that was his first move. And Gusinsky was arrested two weeks after [Putin] was inaugurated—an absolutely shocking precedent of political oppression nobody would expect back then.

Izabella Tabarovsky: When does Nemtsov realize that he can't support Putin anymore and that he has to oppose him and expose who he really is? Is there one crucial moment when that turning point happens?

Mikhail Fishman: Nemtsov’s support of Putin was not absolute, of course, and was very moderate; I would say even provisional. He actually didn't vote for him on election day, but still he was trying to be part of this liberal force. Putin was expressing pro-Western views, and he started the program of reforms, which actually was Nemtsov’s platform, and Nemtsov’s program from 1997, when he was in the government. So why wouldn't [Nemtsov] support them? But of course, he saw that not everything [was going] as he would wish, [with] the [return] of the Soviet anthem in 2000, Gusinsky’s arrest, other signs. But he still plays this team game, until Nord-Ost happens.

That's when, in October 2002, terrorists from Chechnya take hostages in the theater in the center of Moscow. And this hostage crisis continues for a few days. This situation actually is crucial for his relationship with Putin. After that, he understands that Putin is his enemy. They didn't [get] along well before that, for some time already. The regime was changing, and it was visible. The control over political institutions was already established and it was very troubling. That was called, back then, “managed democracy.” That was the term.

That managed democracy failed in Nord-Ost, when it was clear from the very start, and certainly clear after the rescue operation, which left more than 100 people dead in the theater, that this managed democracy actually d[id]n’t value human life. And after Nord-Ost, Nemtsov no [longer] can support Putin. He was deeply involved himself, and he realized that what's [at] stake for the Kremlin and for Putin is not to rescue the hostages, but to get rid of the terrorists. No matter what cost. And that's what becomes so clear during this hostage crisis, which is actually very relevant also today, when we see what's happening in Ukraine. So that's the crucial point. And starting from October 2000, they are enemies, political enemies.

Izabella Tabarovsky: Misha, what makes that episode so relevant to the current moment, can you explain?

Mikhail Fishman: The Kremlin operation never even gave a single effort to save people from the theater. Not a single official negotiator entered the theater to try to talk the terrorists into releasing hostages. What's important to understand about Nord-Ost [is] the idea of how [the] Kremlin treats [its] enemies. “No mercy, no negotiation” is actually the slogan, and it's the actual slogan as well, in which human life costs nothing, it doesn't have any value. It's not important how many people would die, no matter what cost. The terrorists back then, and now Ukrainians, have to surrender, die, be captured…. That's the same, absolutely [the] same scenario, [the] same ideology behind handling this kind of situation.

Izabella Tabarovsky: It's really poignant. Let's talk about Ukraine, because Ukraine played a really important role in Nemtsov's life, starting with the Orange Revolution of 2004. So when and how did Nemtsov fall in love with Ukraine? Because I really think he had sort of a love affair with Ukraine and Ukraine had a love affair with him. So, when does it begin?

Mikhail Fishman: It begins in 2004, during [the] presidential election in Ukraine, during [the] Orange Revolution. It's October, November, and Nemtsov is already out of parliament. Liberals lost everything they had. It's tough time for liberalism and for Nemtsov. Liberalism is discredited. Putin is everywhere and Nemtsov is basically a dissident. He lost everything he had. Putin is dominating the political arena. And [Nemtsov] decides to quit his political career and turn to business, because there's nothing [to] catch in this kind of climate.

And then [the] Orange Revolution happens. Maidan happens. And Viktor Yushchenko, the pro-Western candidate in Ukrainian presidential election, is, of course, a natural ally for Nemtsov. They know each other. They connect as liberal forces and pro-European forces. And of course, he supports Yushchenko on Maidan and in Kyiv, and that's when he is totally caught by Ukraine. Nemtsov is a street kind of political leader. He started with these rallies in [the] late ‘80s, early ‘90s, and [there are] no more such rally rallies in Russia, but in Ukraine, in Kyiv, they greet him. It's again the streets. It's again people on the street, hundreds of thousands. And Nemtsov is in his natural habitat, and he is, of course, happy.

Izabella Tabarovsky: There is a famous phrase that he says on the Maidan in 2014, in which he links the freedom of Ukraine with the freedom of Russia. He says that “we here together must defend your freedom and our freedom.” Can you explain this linkage that he made? What did he mean to say with that? Why were the two connected?

Mikhail Fishman: He believed—we can even actually say he anticipated—that Ukraine’s and Russia's destinies are linked, connected, and he meant that [a] free and democratic and prosperous Ukraine would be a shining example of what Russia actually can achieve, of what Russia can be. And this is also relevant right now, because this is exactly why right now Putin is so determined to destroy Ukraine as a state. Because if he doesn't, it will show the difference between these two worlds. Because Ukraine and Russia, in the eyes of Putin and in the eyes of Nemtsov, are similar. Basically the same people, same nation, same type of society, which lived under Soviet oppression for 70 years. And then Ukraine makes it and Russia doesn't. So Ukraine becomes this example. But for Putin, of course, it works the opposite way. And he feels what Zbigniew Brzezinski famously asserted: that without Ukraine, Russia will never be an empire. That’s Nemtsov’s idea of “your freedom is our freedom,” but the opposite way.

Izabella Tabarovsky: And you also talk about how Putin at that point, right around then, also realizes that Ukraine is absolutely critical, just as you said—it's critical to retain Ukraine in Russia's sphere of influence. And the Kremlin invests [a] huge amount of resources in the victory of a pro-Russian candidate, Yanukovych. And so when he loses, Putin actually experiences the victory of the Orange Revolution as a personal defeat. It gave him a deep sense of insult and humiliation. Can you talk about that?

Mikhail Fishman: [Putin] indeed heavily invested. It somehow happened that just when he took Russian political institutions under control, and he looks at Ukraine, he already looks at the West as his enemy. So he backs Yanukovych. And that's when the presidential campaign in Ukraine starts, and that's when Ukraine is divided, and this division is visible in how the election runs, because western Ukraine is represented and Kyiv is represented by Yushchenko, [a] pro-Western and pro-European type of leader, and the east of Ukraine is represented by Viktor Yanukovych, Kuchma’s last prime minister.

And Putin's take [on] this election, he backs Yanukovych and campaigns personally for him so heavily that the press would write back then that “it looks like he's campaigning in Russia,” so heavily was he campaigning for Yanukovych, let alone how [many] resources were spent to secure his victory. And he loses during the Orange Revolution. And that's when Putin becomes grabbed by Ukraine, and that's when it starts turning into obsession, because it's a personal defeat for him after he so heavily invested in Yanukovych. And it's really very humiliating.

Izabella Tabarovsky: Do you think that what's happening now, this insane determination with which Russia seems to be set on gaining victory in Ukraine, do you think it's related to that? Is it personal for Putin, even today, all these years later?

Mikhail Fishman: Yes, I am absolutely positive about that. Of course, it's not that simple. And all the major wars have various motivations behind them. But this personal humiliation and this personal sense of defeat that Putin started to feel in 2004 and then kept feeling for so many years because Ukraine actually became the only territory where he kept losing, it started in 2004, but that was only his first defeat.

His second defeat happened almost 10 years later, during the second Maidan. During this Revolution of Dignity, during the real uprising, [it turned into a] standoff in Kyiv in [the] winter [of] 2013–2014, and he again lost. Then he invaded Crimea and Donbas. He created these Minsk agreements, the meaning of which would be to insert Donbas back into Ukraine, but actually blocking Ukraine from doing anything politically on its own. That's the idea of [the] Minsk agreements. [That] didn't work. He was hoping that Zelensky as president would get him into the loop and somehow make these Minsk agreements work. And it also didn't happen. And after these several defeats, he starts his invasion this winter.

Izabella Tabarovsky: You already mentioned the Revolution of Dignity in Ukraine, 2013–2014. By that point, Nemtsov is really on the margins. He's fully with the Russian opposition. This is already after the Bolotnaya protests. So then comes the Revolution of Dignity. What was Nemtsov's reaction to it?

Mikhail Fishman: He was absolutely supporting the Revolution of Dignity; he was with Ukrainians and Maidan with his whole heart. But what was different that time, compar[ed] to 2004, [was] that he couldn't go to Maidan because he was banned from entering Ukraine, because Yanukovych was prime minister, [a] pro-Russian president, and he banned Nemtsov personally from entering Ukraine. So he couldn't come to support Maidan, but was supporting it with his whole heart. He was protesting in Moscow during this very dramatic winter, with slogans [like,] “Ukraine, we are with you.” He still stands on his idea that [a] free, independent, European, democratic Ukraine [is] one step forward for Russia to get the same.

Izabella Tabarovsky: You write that the annexation of Crimea crushed Nemtsov and became a personal catastrophe for him. Can you explain that?

Mikhail Fishman: Putin's invasion and then annexation of Crimea came as a total shock, not only to Nemtsov, because nobody could believe it would happen. Back then, eight years ago, such [a] kind of land grab was impossible to imagine. Something that never happened in Europe, since World War Two. And for him, it was a personal catastrophe, a double personal shock, because it was Ukraine, which he really had this kind of love affair with during all these years. And he spent so much time there. He was very present. He was commenting on a weekly basis on Ukraine's television. And second, he saw that, before his own eyes, the principles on which Russia stood—back from the days when he was [a] member of [the] Russian Council, first in 1990, [and] then a government official—these principles are being overturned before his eyes. And that, of course, is a personal catastrophe.

Izabella Tabarovsky: Well, and in fact, you say that the moment when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014 was the end of a Russia that voted for its own independence from the USSR in 1990. What did you mean by that?

Mikhail Fishman: It was the end of [the] Russia which emerged [from] the debris of the Soviet Union in 1990–1991, and that was [the] Russia that Nemtsov helped to build. That was [the] Russia that Yeltsin was leading forward. That was [the] Russia that started its journey as a civilized, modern state, which respects the international rules, respects the borders, respects its own sovereignty, as it appeared in 1990. Even geographically, it became a different country. So that already was the end point of a journey which started in 1990.

Izabella Tabarovsky: And Nemtsov, of course, continued to oppose the war through the very last day. He was killed on a bridge under the Kremlin's walls on February 27, 2015. And at that time, he was working on two big projects related to the war. What were they?

Mikhail Fishman: I would say that he was the strongest, the fiercest critic of Putin's war in Ukraine, which actually started in 2014. Annexation of Crimea was smooth and not bloody. But war in Donbas one month later became a real war. And that's again what Nemtsov could not stand. That became his mission, his main mission—to oppose the war. And that's why he was Putin's fiercest critic back then. It was his slogan that “Putin is war.” He suggested the slogan—that was his slogan for the rally on March 1, 2015, the rally that eventually turned into a mourning procession, after Nemtsov was murdered two days before [it].

His projects were, first, to get people to the streets to oppose the war and make Putin stop it, basically the same way as he behaved in 1995–1996, when he was the main political player, who actually worked on stopping the war in Chechnya, and he brought to Yeltsin the 1 million anti-war signatures. So basically in the same way, he initiated protest rallies in Moscow during 2014 and in 2015 as well.

And his second project was to assemble a report on Russia's victims in Ukraine and how Russian soldiers die in Ukraine. And this truth was vigorously suppressed. I remember the TV Rain reports from Pskov, where many, many soldiers died in Donbas in [the] summer [of] 2014. It was very dangerous for reporters to even go there, because they were followed and harassed by some thugs. And that's when Nemtsov decides that he has to bring [the] truth about this war to Russians, truth that is being hidden from them. That's his main mission. That’s basically what he starts to work on, and then he dies.

Izabella Tabarovsky: You write that news of Nemtsov's death hit people in the heart, as if they [had] heard about the death of a close [relative]. Can you explain this reaction?

Mikhail Fishman: There are situations, some tragic moments in your life, that you always remember when they caught you. Like, you do remember where you [were] on 9/11, when you learned what happened…? [People] usually do.

Izabella Tabarovsky: Absolutely.

Mikhail Fishman: Of course you do. And that's the same type of tragedy. It's when you totally remember [to the] second, where you've been, what you've been doing, how you learned this news. I know it…myself, I know that across Russian independent journalism….Nemtsov was so open. He was so friendly. He had so many friends among journalists, among activists. He was so visible. He was so loud. He was so big. Then when he dies like that, murdered on the bridge, you just can't believe that. It's just impossible to digest this kind of news and it becomes [a] personal tragedy. I know that what I'm describing now is not only my personal emotion, but [an emotion felt by] the thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands of people.

Izabella Tabarovsky: What is Nemtsov's legacy?

Mikhail Fishman: The book is based on the idea that the history of free Russia is the history of Nemtsov and vice versa. His legacy is that he represents, and will always represent, this free Russia, that Russia that now can exist in our mind as an idea only. I see it like this. He was murdered by the war in Ukraine, the energy of violence and death unfolded with the war in Ukraine that Putin started in 2014. So he's also this symbol of opposing the war, on which Russian tyranny would feed when it has no options left.

Izabella Tabarovsky: Misha, thank you so much for this conversation.

Mikhail Fishman: Thank you.

Izabella Tabarovsky: We will put the link to the book in our show notes. Thank you all for joining us. From the Kennan Institute, this is Izabella Tabarovsky, and we will see you on our next episode of The Russia File.