A blog of the Africa Program

Elections in Africa often bring fear and anxiety, and some have resulted in protracted violent conflicts. Elections in 2020 come with additional threats, some beyond the control of the nations involved. The electoral processes in 2020 — which will have taken place in a dozen African countries by the end of the year — are being conducted in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, with its attendant economic slowdown. More dangerously, the countries in the Sahel region — Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso — and neighboring countries in coastal West Africa — Ghana, Togo, and Côte d'Ivoire — are seriously threatened by violent extremism. 2020 is testing the resilience of African governance institutions in the midst of old and emerging threats. On the one hand, nations administering elections are expected to perform beyond the normal to be able to contain the barrage of threats. On the other hand, over-concentration on elections may lead governments to neglect important policy measures, which could, in turn, devastate national economies by, for example, diverting resources needed for security and health.

This blog post assesses the threats facing African countries in the 2020 election year, analyzes nations' institutional capacity to withstand these threats, and proposes policy recommendations for addressing these threats now and in the future.

Potential Threats to African Countries in the 2020 Election Year

Elections in Africa are often accompanied by apprehension, mixed feelings, and anxiety that something unpleasant could happen. Observers see many elections in Africa in 2020 as a test against efforts to erode presidential term limits, as incumbents successfully defied popular protests to impose term limits in Burundi in 2015, and in Togo, Guinea, and Côte d'Ivoire in 2019. Africa's 2020 elections are also testing other democratic checks and balances, which has direct consequences for stability on the continent. The general sense of apprehension this electoral season stems from the fact that, over the years, elections in Africa have often produced disturbingly violent outcomes.

In the midst of the traditional challenges that threaten Africa's democracy, new and emerging security threats pose even more danger to the stability of African nations. The coronavirus pandemic has negatively impacted the entire world, and developing countries with weak health infrastructure[1] and limited capacity to deal with emergencies have been most seriously affected. African nations facing elections in the midst of the pandemic are arguably the most vulnerable of all. For example, unbudgeted costs for personal protective equipment for electoral officials and voters, extension of voter registration periods to accommodate delays caused by social distancing protocols, and the need for special education by elections management bodies all add additional costs to administering elections in Africa.

Can African Governance Institutions Respond to These Threats?

A common dictum for good governance is that there is the need for strong institutions but not strong personalities. However, African states have tended to be built around "Big Men" and organized around political elites, whereas state institutions tend to be weak, under-resourced, and over-politicized, and thus unable to deliver required public services. All-too-common governance weaknesses across Africa include: 1) filling top positions of state institutions with political party members; 2) victimizing and disempowering public officials suspected of sympathizing with opposition parties; 3) short-changing professionalism, discipline, and service ethics in government; 4) overriding public appointment decisions with clientelism, and; 5) victimizing and disparaging civil society organizations (CSOs) that seek to provide independent analysis of governance and press governments to do the right thing. The cumulative result is that African countries all too often are saddled with weak state institutions that are starved of resources and denied the independence needed to perform their governance duties.

Recommendations

In order to strengthen the ability of African governance institutions to address threats to the effective administration of elections, the following measures are recommended:

- African CSOs should not be impeded in their work to raise citizens' awareness and make them more conscious of the affairs of their states. This would encourage voters to demand responsible and accountable governance, and elect leaders inclined to improve governance of the state.

- Africa's regional institutions should intensify programs aimed at checking governance abuses and promoting good governance among member states. The African Union's Peer Review Mechanism should be revamped and repackaged in order to effectively assess the governance performance of member states. Findings from independent assessment mechanisms and bodies such as Afrobarometer, Transparency International's Corruption Barometer, and Human Rights Watch must be used to demand accountability in governance and reprimand those countries negatively cited in the reports.

- The United Nations and other international development partners should redesign their strategies of support to Africa. Governments with a penchant for autocracy should be sanctioned and cut off from all assistance. This would strengthen accountability in African governance. The United States, which historically has had significant leverage in calling African leaders to account, should be firmly and consistently willing to sanction or otherwise penalize those African leaders who abuse established legal and democratic principles involving elections.

Conclusion

2020 has been a challenging year for Africa, especially for states holding elections. Their national budgets are stretched by concurrent expenses related to administering elections, mitigating COVID-19, and addressing the growing security threat posed by violent extremist groups. Yet too many Africa states have weak institutions that are unable to withstand shocks such as pandemics, natural disasters, and insurgencies. To address this, there is a continent-wide need to build a more democracy-minded citizenry and stronger governance institutions. Additionally, there is an imperative for stronger sanctions by regional bodies as well as the international community aimed at forcing greater accountability in African governance.

Paul Nana Kwabena Aborampah Mensah is a Senior Programs Officer and Team Leader for Local and Urban Governance and Security Sector Governance for the Ghana Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana). He is a former Southern Voices Network for Peacebuilding Scholar.

[1] Ghana like many other African countries did not have enough ICU centers and testing facilities for the virus in the hospitals. The government has just announced intentions to build 16 regional hospitals and special centers have been started to take care of such pandemics now and in the future.

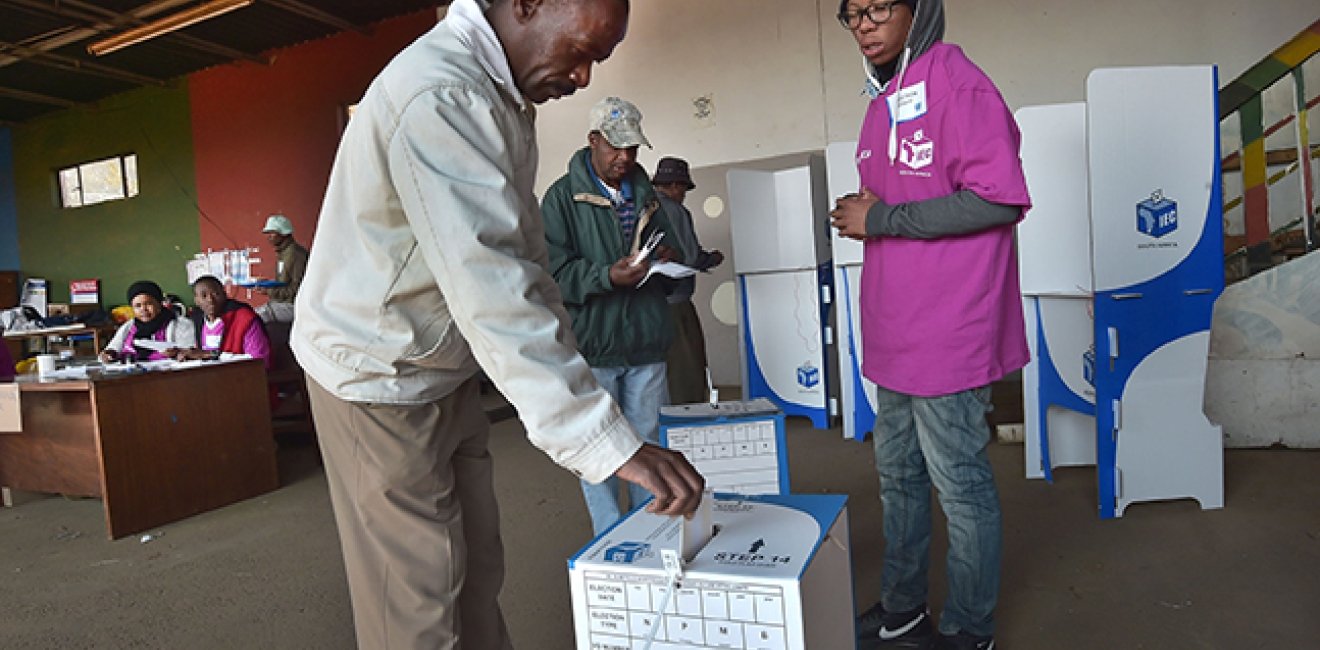

Photo credit: South Africans cast their vote in Diepsloot during the 2016 Local Government Elections. Credit: Government of South Africa/GCIS. Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/governmentza/28145143644/. License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/.

Author

Africa Program

The Africa Program works to address the most critical issues facing Africa and US-Africa relations, build mutually beneficial US-Africa relations, and enhance knowledge and understanding about Africa in the United States. The Program achieves its mission through in-depth research and analyses, public discussion, working groups, and briefings that bring together policymakers, practitioners, and subject matter experts to analyze and offer practical options for tackling key challenges in Africa and in US-Africa relations. Read more

Explore More in Africa Up Close

Browse Africa Up Close

The Innovative Landscape of African Sovereign Wealth Funds