A blog of the Africa Program

From September 21st to the 23rd, more than sixty people in Nairobi, Kenya lost their lives in an attack on the Westgate shopping mall by a religious terrorist group known as Al-Shabaab. This was not the group's first crime, as they have been attacking churches and buses in the country for some time in retaliation for Kenyan intervention in Somalia. One week later, Boko Haram, another jihadist group, massacred about forty students in an agricultural college in northern Nigeria to emphasize their opposition to Western education, which they consider a sin. Since 2009, attacks by this Islamic sect have killed thousands. Radical religious terrorism now poses a real threat to durable peace in Africa, especially in the Sahel. In the last few decades, the region has become the main hideout of jihadist movements who are therefore able to make alliances. Mali recently saw its sovereignty jeopardized by a coalition of small groups who used jihadism to further their economic and political goals. Religious terrorism had therefore gained ground in Sub-Saharan Africa and, according to French political commentator Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Monclos, "the terrorist forms of radical Islam can be considered a new phenomenon… We are seeing a religious insurrection turn to criminality in the name of radical Islam" We are witnessing "porosity between religious activism and criminality."

Radical Islam and Polarization

What should be most feared, however, is the menace posed by the infiltration of religious radicalism into the usually peaceful cohabitation of Muslims and Christians in Sub-Saharan Africa. Islam in Sub-Saharan Africa is known for its tolerance and its ability to adapt to religious difference. But, if we are not careful, things may change to benefit radicalism, Christian as well as Muslim. Indeed, analysts show that the globalization of African Islam has "put it into contact with its most conservative and radical versions," and that "for three decades, the dynamics of reorganization of the religious space in Africa have joined economic and intellectual local actors with transnational religious actors, bringing about a redefinition of social norms in the public sphere and in the region." Obviously, violent religious radicalism is consistently condemned by Muslim and Christian religious authorities in the vast majority of Africa countries. The victims of violent Islamic groups are not only non-Muslims, but also Muslims of the African Islamic brotherhoods seen by reformers as Islam corrupted by heterodox practices. Nevertheless, terrorist jihadism represents a real menace to peaceful relations between Christians and Muslims, as certain Christian fundamentalists do not hesitate to respond to violence with violence. Where churches and chapels are burned, mosques are also vulnerable to retaliation. Violent Islamism could also provoke the radicalization of Christian fundamentalists and exacerbate intercommunity conflicts.

Furthermore, attempts to polarize conflict between Christians and Muslims are no longer unique to northern Nigeria, known for recurring interreligious violence. Today many African countries are showing signs of vulnerability. Côte d'Ivoire, during the political crisis of the last ten years, narrowly escaped an attempt to use religion to transform a primarily political conflict into a confrontation between the majority Muslim north and the majority Christian south. In the last few years, Guinea saw a recurrence of interethnic conflicts which degenerated into interreligious confrontations between Christians and Muslims, particularly in the region of Nzérékoré in the Guinée forestière region. In the Central African Republic, the recent power-grab by the Seleka rebel movement, infiltrated by Chadian and Sudanese islamists, was accompanied by attacks and systematic pillages of institutions of Christian persuasion, exacerbating tensions between Christians and Muslims.

The Future of Secularism in Africa

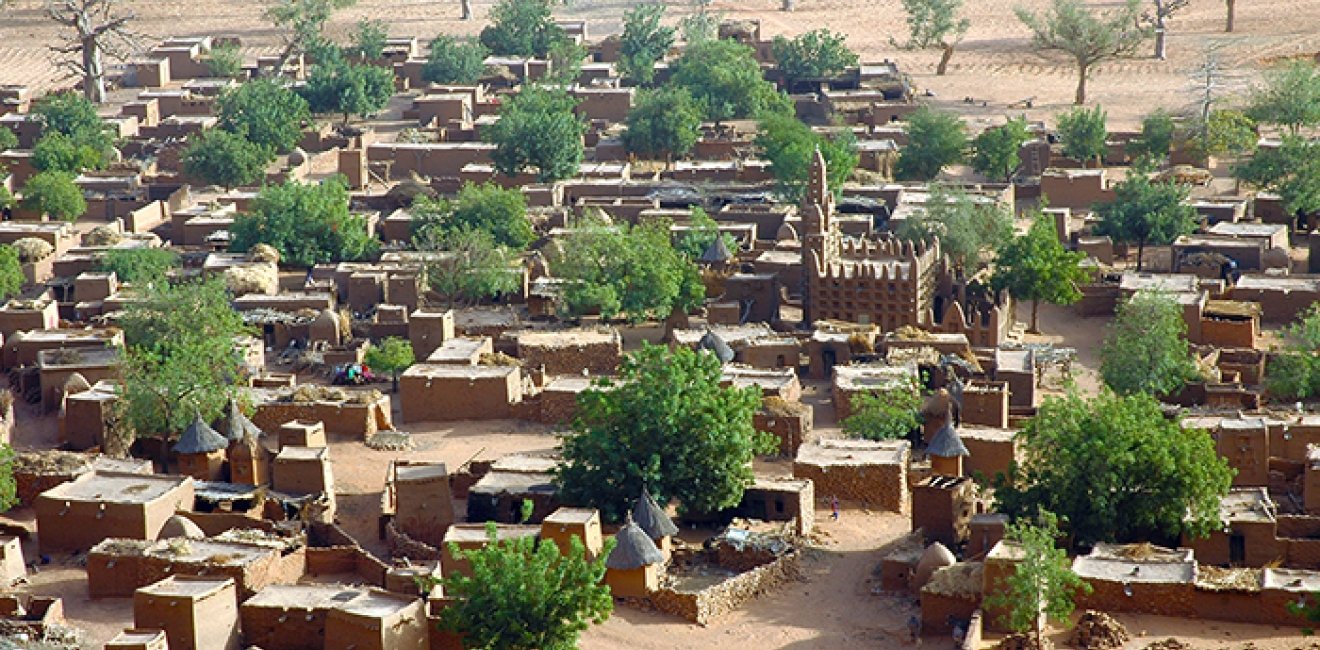

The problem is real and also affects the future of the secular state in Africa. Africa remains a profoundly religious continent and the public role of religions deserves more attention that it has received in the past. From the highest levels of the state down to the grassroots, the religious or mystical reading of public life remains predominant. It is necessary to speak of an African voice of secularism and secularization, itself plural, which distinguishes itself from the occidental voice. The majority of African countries are secular according to their constitutions, which indicates that in principle they do not favor any particular religion. Even the Sub-Saharan African countries with strong Muslim majorities, like Senegal, Mali and Niger, opted for secularism, which made it possible for Christian minorities and traditionalists to live peacefully alongside Muslims. It is this fundamental benefit which is the target of radical religious movements that recommend a return to Christian or Muslim states.

Many sociologists of religion see in religious radicalisms a reactionary posture or, more precisely, disguised forms of sociopolitical protest against some kind of marginalization and exclusion expressed in antimodernist and anti-occidental language. In any case, injustice, poverty and social inequality favor the growth of religious radicalism in Africa. As two analysts have written about Mali, "for shopkeepers and youth without employment or resources, these terrorist groups represent important opportunities for revenue in regions where the inhabitants consider themselves abandoned and forgotten."

Collaborative and Nonviolent Solutions

It follows that to counter this phenomenon, on the rise in certain regions of Africa, security and repressive solutions will not suffice. We must attack to root of the problem: the poverty and social exclusion which, in many of our countries, exposes a fringe of the population, especially youth frustrated by and excluded from the benefits of modernity, to religious, fundamentalist, and intolerant indoctrination. The struggle against violent religious radicalism in Africa, therefore, also includes economic and political solutions.

This struggle also includes education, and countries must face up to the question of religious indoctrination. It will be appropriate to involve religious elites in the struggle against religious radicalism, first and foremost in the promotion of religious tolerance in the education of youth. This is fundamental to peaceful coexistence in an irreversibly pluralist world. In Côte d'Ivoire, for example, during the period of crisis from 2000 to 2011, the religious elites assembled in an association called the "Forum des confessions religieuses" and worked to stop the political conflict from becoming interreligious. There were attempts to use religion to pit Christians against Muslims. Certain incidents at churches and mosques could have led to direct confrontations, but measured interventions by religious leaders contained frustrations and Côte d'Ivoire avoided an escalation of religious violence. Interreligious dialog is therefore important in preventing violence and, faced with the menace of religious terrorism, Christians and Muslims must collaborate.

Dr. Ludovic Lado is an anthropologist of religion and researcher at the Centre de Recherche et d'Action poir la Paix (CERAP) in Abidjan.

Translated from French by Teo Lamiot, Staff Intern for the Africa Program and the Project on Leadership and Building State Capacity at the Wilson Center.

Author

Director of Institute of Human Rights and Dignity, Center of Research and Action for Peace

Africa Program

The Africa Program works to address the most critical issues facing Africa and US-Africa relations, build mutually beneficial US-Africa relations, and enhance knowledge and understanding about Africa in the United States. The Program achieves its mission through in-depth research and analyses, public discussion, working groups, and briefings that bring together policymakers, practitioners, and subject matter experts to analyze and offer practical options for tackling key challenges in Africa and in US-Africa relations. Read more

Explore More in Africa Up Close

Browse Africa Up Close

The Innovative Landscape of African Sovereign Wealth Funds