A blog of the Latin America Program

“To these people who say democracy is being dismantled, my answer is yes, we are not dismantling it, we are eliminating it, we are replacing it with something new,” Félix Ulloa, the vice president of El Salvador, told The New York Times earlier this month, days before El Salvador’s presidential election.

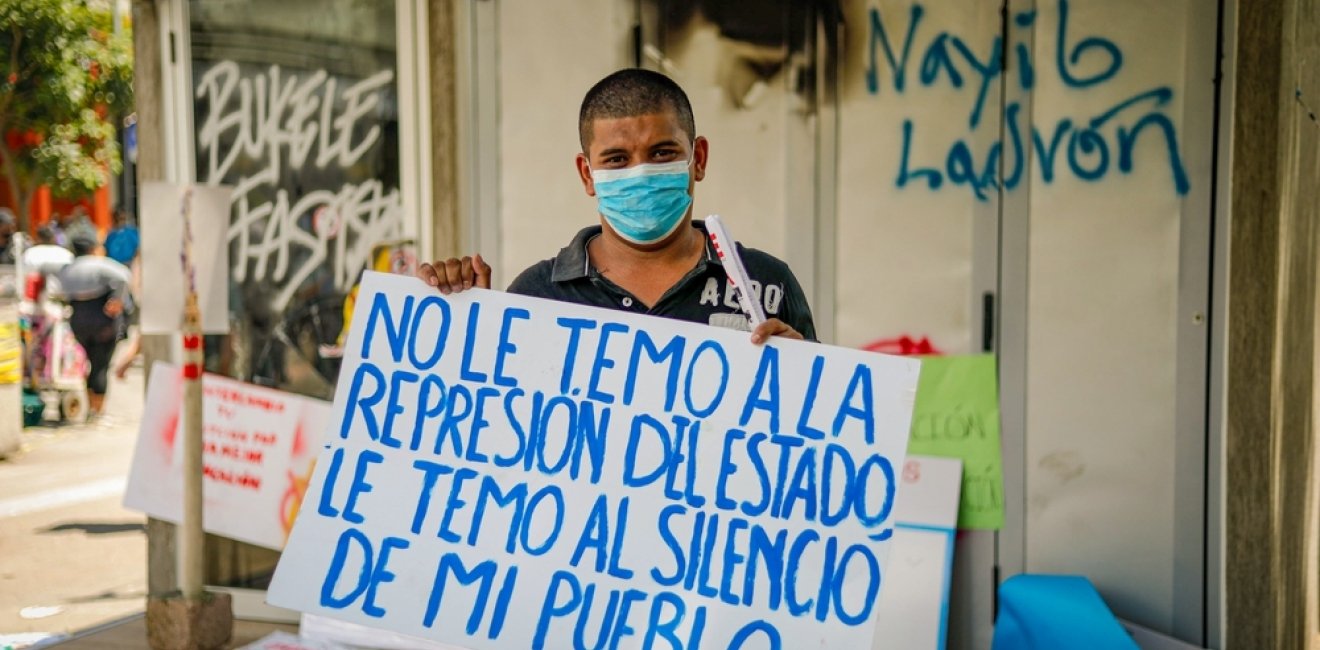

Two days after Ulloa’s blunt declaration regarding the direction of President Nayib Bukele’s administration, the candidate amended his running mate’s statement, insisting he was constructing El Salvador’s first “true” democracy, discarding a broken system that failed the population and served the interests of only a corrupt few. Bukele’s determination to remake the Salvadoran state is clear. His political party, after all, is named Nuevas Ideas. However, the “something new” promised by Ulloa looks suspiciously like something old, one-man rule. Even so, Bukele’s popularity is complicating efforts to counter his corrosive effect on democracy, with implications beyond El Salvador.

The ‘something new’ promised by Ulloa looks suspiciously like something old, one-man rule. Even so, Bukele’s popularity is complicating efforts to counter his corrosive effect on democracy.”

That is troubling. In the United States, Latin America experts argue that democracy matters more in this hemisphere than in other regions for reasons of geography and cultural proximity. Undoubtedly, the US record defending democracy in the region is mixed, blemished by a history of interventions against elected governments and support for authoritarian right-wing governments during the Cold War. Still, beginning in the late 1970s, the United States has largely supported democrats against threats to democracy from the right and left. That policy is based on the idea that democracy is more likely to produce sustainable social, political, and economic gains to satisfy popular aspirations and undermine the logic of revolutionary change. This argument is not only heard in Washington; on September 11, 2001, 34 countries in the region signed the Inter-American Democratic Charter, pledging to “promote and defend” representative democracy.

Nevertheless, more than 20 years later, democracy is under strain in many parts of the region and the Inter-American Democratic Charter feels more like a high point than a turning point. In that context, the Biden administration has viewed Bukele with wariness. His storming of the Salvadoran Congress in 2020, alongside soldiers and police, to pressure lawmakers over a budgetary dispute raised alarm bells. So did his tendency to use state instruments to persecute critics; the presence of corrupt figures in his inner circle; his hostility to independent journalists; and his disregard for constitutional constraints on his power. Bukele’s economic mismanagement, including his bet on Bitcoin to spur growth, elevated concerns that an economic failure there could add vast numbers of Salvadoran migrants to the 20 million people already on the move across the Americas.

For now, El Salvador is not Nicaragua, where the regime imprisoned all major opposition candidates before the last election. But nor can it be called a constitutional republic, given the circumstances of its February 4 elections. Bukele held the election under a state of emergency and won a second term despite a constitutional ban on reelection.

That poses a challenge for US policymakers because Bukele’s successes, especially in fighting criminal gangs, and his popularity tend to overshadow his authoritarian behavior and stand in contrast to the inability of many democratic governments to address violent crime. That is not a minor issue. Latin America and the Caribbean is among the most violent regions in the world, accounting for around one-third of all murders though it is home to just 8% of the world’s population, according to the International Crisis Group.

El Salvador is not Nicaragua, where the regime imprisoned all major opposition candidates before the last election. But nor can it be called a constitutional republic, given the circumstances of its February 4 elections.”

El Salvador was long among the most violent countries in this violent region, with a history of failed negotiations between governments and gang leaders that allegedly continued into the Bukele administration. That changed in 2022 following the announcement of a state of exception that suspended civil liberties and led to the arrest of 75,000 people suspected of gang affiliation. Salvadorans, at least those who have avoided arbitrary detention, are generally, and understandably, relieved by the suppression of gang violence. The vastly improved security climate, and Bukele’s sleek public messaging, have restored a sense of national pride. In a region that features mass migration, stagnant economies, and increasingly powerful organized crime groups, El Salvador sometimes feels more like a success than a crisis to many observers outside the country.

The problem is that the policies that brought Bukele quick success carry the seeds for long-term failure. The concentration of power in the hands of a single individual intolerant of competition is a common pattern in Latin America–one that almost always leads to policy errors and democratic decline. There is a reason the most autocratic nations in the hemisphere are also its largest sources of migrants. In El Salvador, for example, the same opaque decision-making apparatus that brought the gangs to heel also led to the failed Bitcoin experiment and has discouraged domestic and foreign investors.

As a result, the United States faces the awkward challenge of dealing with a popular, twice elected leader, unfettered by constitutional guidelines.

Public criticism by the US government of Bukele’s subversion of democratic institutions seems to have migrated to private channels, and demonstrations of public engagement with Bukele are now common. Even so, in congratulating Bukele on his controversial reelection, Secretary of State Antony Blinken emphasized the importance of “fair trial guarantees and human rights.” But Bukele seems impervious to international pressure, public or private. In hisvictory speech, he assailed foreign critics, asking, “Why do they want to see the blood of Salvadorans?” That dynamic of intolerance for even mild critiques seems likely to continue.

That approach might be effective, especially where US goals do not run counter to core interests of the Salvadoran government, such as cooperation to improve El Salvador’s economic performance. It will be less effective when Salvadorans interpret the lack of public US criticism of Bukele’s undemocratic behavior as tacit approval of such actions. More distressingly, US silence in the face of human rights abuses signals to others in the Americas that patience and popularity are the recipe for swatting away criticism from Washington and undermining the Inter-American Democratic Charter.

Author

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

Dengue Haunts South America’s Summers

Lessons from Costa Rica’s Economic Transformation

Women and Latin America’s Digital Revolution