A priority for the first 100 days of the new government is the organization of the G20 in Brazil. To this end, Lula's administration must set a vision and outline the themes of the Brazilian presidency, appoint the members of the organizing team, define the host city, coordinate with the current Indian presidency of the bloc, and prepare background studies and public debates if it wants to set a transformational agenda and chart a path for collective action on critical global issues.

Only through collective action will the G20 be able to strengthen all countries' positions in the face of the transformations shaping the future of the world and achieve the goals set by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Agreement.

The first of these transformations is the rise of Asia. China, India, Indonesia, Japan, and South Korea altogether account for 32% of trade flows, 39% of GDP (PPP), 63% of the population, and 18% of the geographical coverage of the G20. India is expected to rise to the world's second-largest economy by 2050. Asia is also setting the pace of the digital-technological revolution and inauguring a more competitive, sustainable, and innovative productive paradigm.

This paradigm is born amid nearshoring, reshoring, and powershoring of industrial processes and other structural changes in global value chains that will determine countries' competitiveness, access to markets, and the future of work. The G20 can support the world's transition to industry 4.0 and digital agriculture through initiatives that ensure both processes happen in a timely, competitive, and sustainable way for the Global North and South alike.

The second transformation is the global energy transition and the impact of China's decarbonization on global energy markets. As the world's largest consumer of primary energy, a contraction in China's coal, oil and gas demand may severely reduce imports of these products over the long term. Positive impacts are expected in global nuclear and hydropower markets, as China plans to increase nuclear power sixfold and double hydroelectricity.

Whether countries will weather the impacts or reap the benefits from a zero-carbon China depends on their export profile and readiness to transition to a low-carbon economy. The G20 can help countries anticipate these impacts and identify elements that could contribute to their repositioning in low-carbon industries. For example, the bloc could encourage the development of green standards and taxonomies to increase the interoperability among carbon markets and the fungibility of carbon credits worldwide. Building on the natural vocation of countries like Brazil for the generation of carbon credits, this initiative could be further associated with biodiversity protection and poverty eradication in the Global South.

The third transformation is the disruption of food supply chains and the global hunger crisis. Fueled by conflict, climate shocks, and Covid-19, the problem escalates as the war in Ukraine drives up the cost of food, fuel, and fertilizers. In just two years, the number of people facing, or at risk of, acute food insecurity increased from 135 million in 53 countries pre-pandemic to 345 million in 82 countries today.

Leveraging on members’ experience, the G20 can help meet the world’s immediate food needs while supporting initiatives that build resilience. Brazil and China, for instance, have eradicated hunger and poverty while Brazil and the U.S. are agricultural powerhouses. The measures announced at the G20 meeting in Bali last year could be complemented by the launch of a global alliance to rally support and finance for initiatives that aim to increase agricultural productivity, end hunger, and eradicate poverty.

Charting a path for collective action will require the mobilization of resources, including through the Inter-American Development Bank and the New Development Bank - where Brazil currently holds the presidency. The Brazilian government could further aim to expand access to special funds like the China-Latin America Cooperation Fund, the Investment Fund for China-Latin America and the Caribbean Industrial Cooperation, and the Special Fund for China-Latin America Infrastructure. Monitoring pledges made in previous G20 meetings and other initiatives, like the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, would also serve the purpose.

What will be achieved will depend on Brazil’s ability to build bridges between the world’s largest economies and offer a positive and transformational agenda that speaks to the needs and reality of the Global South. Today, the G7, the group of the largest developed economies (USA, Germany, Japan, France, UK, Canada, and Italy), is very cohesive and has generated initiatives that have fed the G20.

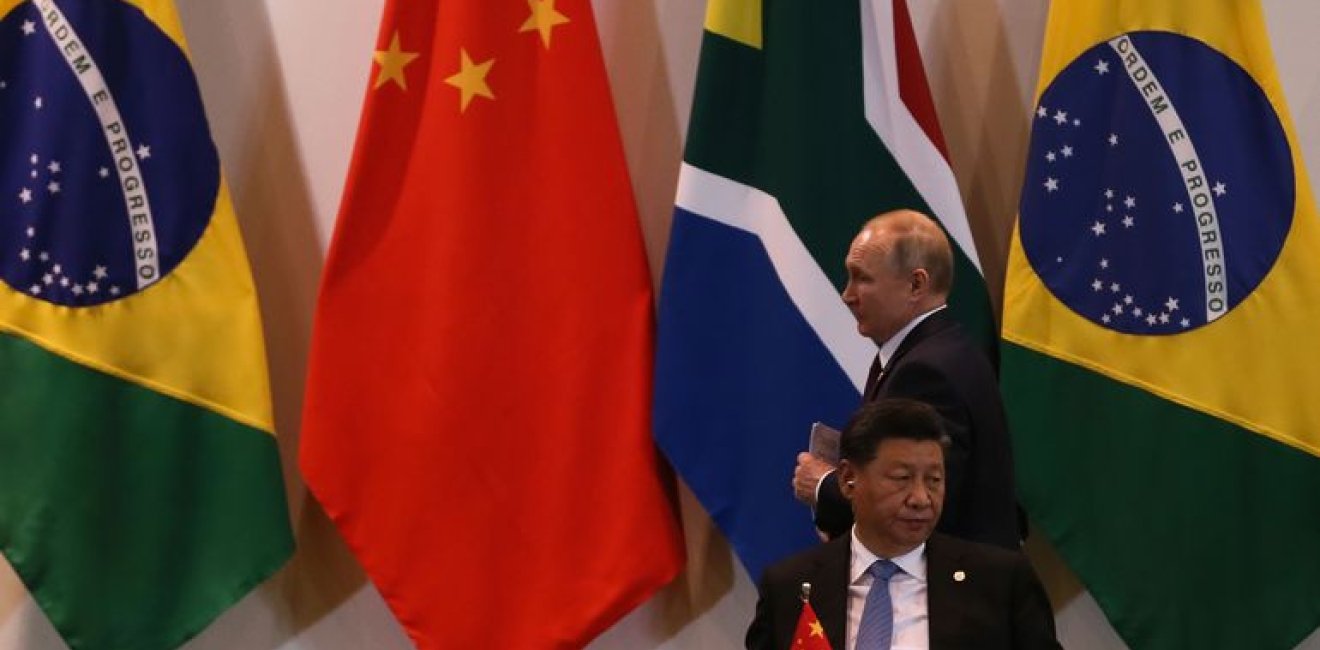

The scenario is more fragmented on the side of emerging economies, with Russia and China fueling criticism on the BRICS, on the one hand, and the revitalization of IBSA as a space for political coordination among the Indian, Brazilian, and South African rotating presidencies of the G20, on the other. The new government must act fast and with purpose, reassuring the world that it stands committed in addressing some of the major global challenges of our time.