A blog of the Polar Institute

On December 13th, the US Department of Defense and Canadian government combined to award a total of up to $25M US in grant funding to Fireweed Metals, a Canadian mining development company, to advance the Mactung tungsten project toward a final investment decision and enable Fireweed to build some necessary project infrastructure. By funding specific requirements of the mine – permitting work, development studies, and infrastructure – that are among the most important for Arctic critical minerals projects and the least financeable by private capital, the US and Canada’s support for Mactung can be seen as a model for how to best advance critical minerals production in the Arctic.

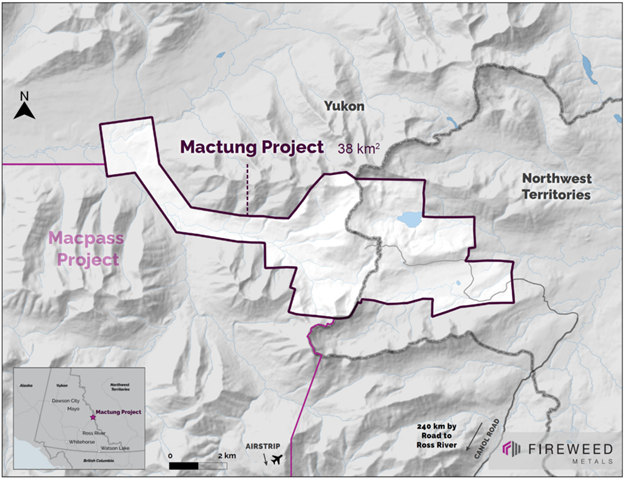

Mactung, one of the world’s largest tungsten deposits, sits east of the Continental Divide on the border between the Yukon and the Northwest Territories. It is remote even by the standards of the Canadian Arctic; the closest human settlement, the 355-person First Nation community of Ross River, is 200 km away. Two airstrips, one on either side of the provincial boundary, provide access in winter. The deposit (known as Mactung) was first discovered in 1962 near the MacMillian Pass, but has never been developed, despite its world-class size and high grade.

That may change in the coming years.

The Mactung project’s location. Image credit: Fireweed Metals

Tungsten is a minor metal in terms of market size (est. $5 billion in 2024) and is mostly used in tungsten carbide drill bits and other applications that call for particularly hard metals or alloys. DOD is funding Mactung through Title III of the Defense Production Act of 1950, which “targets investments that create, maintain, protect, expand, or restore domestic industrial base capabilities that are critical to the Department and the American Warfighter.” Only about 8 percent of tungsten worldwide is actually used directly in defense applications, according to the International Tungsten Industry Association, but the language of the DOD award emphasizes the criticality of tungsten nonetheless, calling the metal “a critical input for military-grade steel production, aerospace components, munitions, and ground vehicle armor.”

China currently controls 80 percent of the tungsten mining and processing supply chain and has been ramping up restrictions on tungsten exports to the US in recent months (along with other minor, but critical and overwhelmingly China-dominated metals like gallium, germanium, and antimony). The US has been proactively working to scale back dependence on Chinese tungsten; the 2022 REEShore Act prohibits the use of Chinese tungsten in military technologies starting in 2027 (bizarrely defining tungsten as a “rare earth metal”), and the US announced 25 percent import tariffs on Chinese tungsten products the day before the Mactung funding decision.

The Mactung grant can arguably be seen as a blueprint for US polar leadership with respect to critical minerals, as well as highlighting the priorities of US leadership in the Arctic. Mactung is far from the only current or potential source of ex-China tungsten, nor is it likely to be one of the first new ones developed. On its own, the joint grant is not necessarily a difference-maker for the project. Fireweed, backed by the Lundin Group, a Swedish/Canadian mining consortium, has been steadily advancing Mactung with private market funding for several years. But in fact, what is interesting about Mactung is that DOD is willing to support a non-US-based Arctic mining project at this crucial pre-construction stage in its development.

In the mining world, companies often lament an “orphan period” after the excitement of discovery of a new resource has faded and the long work of economic studies, permitting, financing, and ultimately construction remains. A disproportionate number of Arctic mining projects languish indefinitely in the orphan period, held by small junior companies with little hope of building the mines on their own. The biggest reason for this, as Mactung itself shows, is the lack of regional infrastructure. The deposit was discovered sixty-two years ago and is arguably the best undeveloped tungsten project on earth today – yet its location has ensured that it has remained unmined. The last project owner before Fireweed went bankrupt in 2014.

The Mactung funding grants are important because they address some of Fireweed’s actual biggest current needs – funding in this pre-construction phase of advancing economic and engineering studies and permitting. On the Canadian government side, the funding will also specifically target crucial infrastructure, “improvements of approximately 250 kilometers of road, upgrades to an existing transmission line between Faro and Ross River, and the construction of a new transmission line from Ross River” to the project site.

This approach to funding Mactung is distinct from many previous government efforts to help Arctic projects advance. The US EXIM Bank, for instance, issued a Letter of Interest for a loan for the construction of the Citronen Fjord zinc project in northeast Greenland relatively early in its diligence process, but then conducted further diligence over multiple years without actually providing any project funding. (After more than two years, EXIM ultimately withdrew its LOI for Citronen Fjord at the project owner’s request, largely because of unfavorable movements in both interest rates and zinc prices.) The EXIM approach of only offering funding at the time of a construction decision, in the author’s view, does not work well for many Arctic projects, because it neglects to fund projects during their long pre-construction orphan period when companies are most likely to fail. EXIM and the government of Greenland also assumed in the case of Citronen Fjord that the company would bear 100% of the costs of constructing a port and other transport infrastructure, something that most would-be Arctic miners would struggle with.

There is a passing reference to “engagement and consultations with First Nations” in the Canadian funding decision, which is critical and deserving of further emphasis. Mactung sits on the traditional lands of two First Nations groups as well as the Sahtu Settlement Area (on the NWT side of the border). In a statement to CBC, the Na-Cho Nyäk Dun expressed concerns with potential pollution and water consumption from the mine as well as “moral opposition” and “ethical questions” regarding tungsten’s applications in munitions. Thus far, Fireweed has received all required permits, and the Yukon Environmental and Socio-Economic Board had recommended approval of the Mactung mine (after more than five years of review) when Mactung’s previous owner applied. But years of further permitting and negotiation of an Impact Benefit Agreement lie ahead for Fireweed, and a recent heap leach pad failure at a gold project in the Yukon that released as much as 300,000 cubic meters of cyanide solution has brought the environmental dangers of mining disasters to the forefront in the territory. The Na-Cho Nyäk Dun are asking for a federal audit of the disaster, as well as an investigation of “broader issues surrounding mineral management in the territory.” Bi-national support for the mine will mean little if the First Nations groups that host it are not active and supportive participants and stakeholders.

DOD’s grant decision for Mactung has the hallmarks of a successful US approach with respect to financing critical minerals projects in the Arctic. It has “crowded in” additional host government investment; it is supporting a project that is undeniably relevant to US national security interests; it is made at the lifecycle stage at which the mining company is most in need of non-dilutive funding to continue advancing the project, and where every dollar counts most (and thus the grant can be small in terms of absolute dollars). Meanwhile, the Canadian grant recognizes the two paramount realities of Arctic economic activity. One is that even world-class projects may be uncompetitive without initial direct government support for project infrastructure. The second is that buy-in from Indigenous Arctic communities, as the subsequent infrastructure funding plan calls for, is essential. This latter principle in particular will be tested in the coming years; Fireweed will have to conduct detailed environmental and other studies to mitigate any concerns that the Na-Cho Nyäk Dun and other First Nations groups have. The joint grants are an important step to help advance these.

- [1] Disclaimer: The author holds no securities of Fireweed Metals and has no financial interest in the project; the information contained herein is for general interest.

Author

Polar Institute

Since its inception in 2017, the Polar Institute has become a premier forum for discussion and policy analysis of Arctic and Antarctic issues, and is known in Washington, DC and elsewhere as the Arctic Public Square. The Institute holistically studies the central policy issues facing these regions—with an emphasis on Arctic governance, climate change, economic development, scientific research, security, and Indigenous communities—and communicates trusted analysis to policymakers and other stakeholders. Read more

Explore More in Polar Points

Browse Polar Points

Greenland’s New Governing Coalition Signals Consensus

Fulbright Arctic Initiative IV Scholar at the Polar Institute