A blog of the Latin America Program

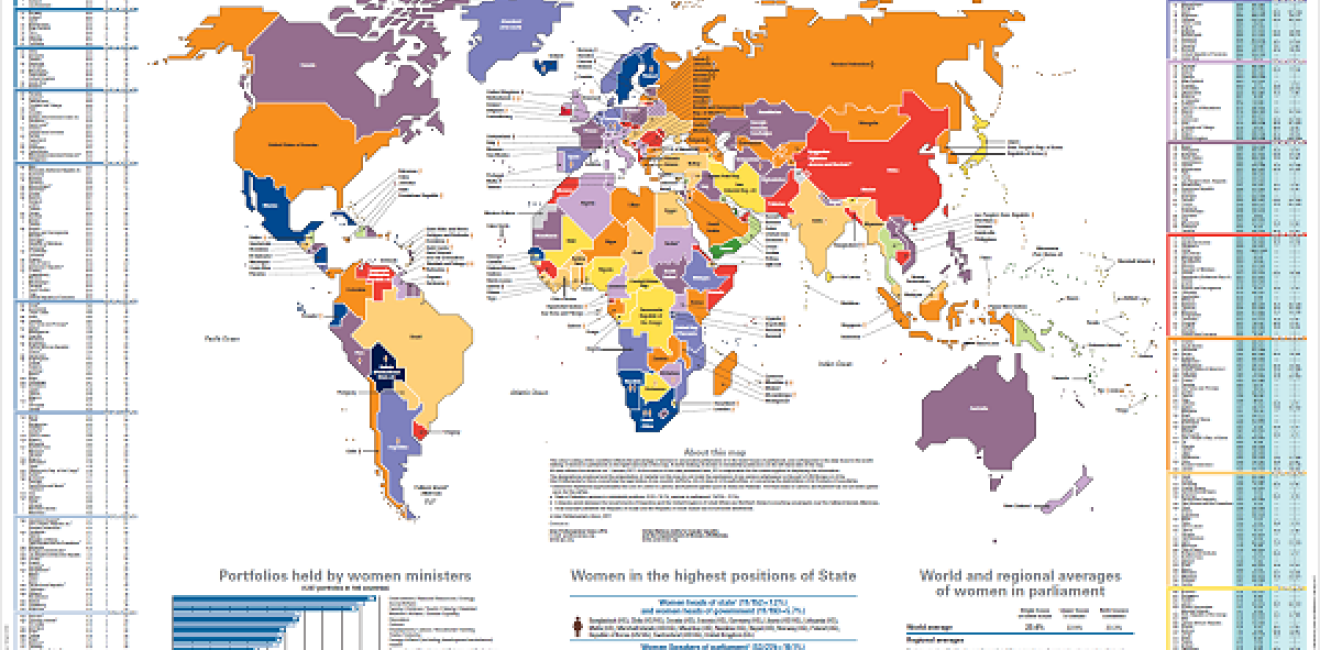

By law, women will occupy at least half of Argentina’s legislature by 2019. But in the executive branch, the country has a long way to go. A new report from UN Women shows the country’s continued struggle to elevate women to cabinet positions. The report, “Women in Politics,” ranks Argentina 95th out of 187 profiled countries for the number of women in ministerial positions. Of the country’s 23 ministries, only four, or 17 percent, are led by women. Argentina’s security minister is a woman, but the other high-profile ministries, including finance and defense, are led by men. Last month, when President Mauricio Macri sacked his commerce and energy ministers, he swapped men for men.

For its congress, Argentina was an early adopter of a gender quota system – in place since 1991 – that has helped increase the number of women in the Argentine legislature. In the UN Women report, Argentina ranked 16th in that category, with 39 percent of seats in the Lower House and 42 percent of seats in the Senate held by women. Argentina has also led the region’s efforts to address domestic violence and femicide, through its high-profile Ni Una Menos civil society movement. In June, Argentina’s Lower House approved legislation to decriminalize abortion, an issue now before the Senate. Historically, women have held some of Argentina’s highest government positions, including the presidency, vice presidency and governorship of Buenos Aires Province, home to 40 percent of the country’s population.

At the same time, the low number of female ministers shows what Argentina’s national politics might look like without the gender quota. Meanwhile, despite the increased presence of women in the Argentine congress, the country is just now attempting to address its gender pay gap, among the worse in the region. Today, Argentine women earn only 76 percent of the salary of men in similar positions, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Lights out: Crime curfew

Argentina is among the ten countries where locals are most afraid to walk alone at night, according to the latest Global Law and Order report from the pollster Gallup. The survey found that only 40 percent of Argentines feel safe on a solo nighttime stroll, compared to a 68 percent global average. Over all, Argentina received a low rank on the index – tied with Brazil, and just above Zambia and Uganda – based upon surveys about confidence in the police and experiences with robberies or assault.

Argentina’s struggles are par for the course in Latin America, the worse performer in Gallup’s global index, where only 42 percent of the public has confidence in the local police, compared to 82 percent in the United States and Canada. Nevertheless, insecurity and drug trafficking in Argentina – especially in gangland Rosario, in Sante Fe province – have become leading public concerns, and were important factors in the last presidential election.

Politically, however, crime is a winning issue for Mr. Macri, at least compared to economic management. Last year, cocaine seizures more than doubled in Argentina, and the country’s murder rate fell by 10 percent, according to official data. In an April poll by Giacobbe & Asociados, 39 percent of respondents identified the president’s coalition, Cambiemos, as the political movement best equipped to address insecurity, more than double the second-most popular response, kirchnerismo (17 percent). In the Economist Intelligence Unit’s 2017 Safe Cities Index, Buenos Aires was the top performer in Latin America.

Economic rescue: Political landmine

After two months of economic instability, by mid-July, Argentina’s International Monetary Fund agreement and major cabinet changes had managed to stabilize the peso. But the damage had been done: The peso is the worst performing major emerging market currency, logging a 30 percent decline since January. As a result, inflation expectations increased from 25 percent in April to 30 percent in June. Expectations for the economy are at the lowest level since Mr. Macri took office.

Fortunately for Mr. Macri, the potentially radioactive political costs of the IMF bailout have been muted, as the Peronist opposition has been unable to capitalize on his unpopular decision. The government hopes Argentines will forget about the bailout long before next year’s presidential election. In the meantime, the international financial community remains in Mr. Macri’s corner. In detailing the $50 billion bailout earlier this month, IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde praised Argentina’s reformist government for its “systemic transformation of its economy,” and blamed the recent crisis on “challenging circumstances” mostly outside of Mr. Macri’s control.

But when one digs deeper into the document, it becomes clear that the IMF program is full of potential landmines that could imperil Mr. Macri’s reelection. Most significantly, it expects Argentina to balance its budget by 2020 – an ambitious goal that the IMF recognizes would require a “significant up-front adjustment.” Though the IMF supports preserving social programs, the fiscal adjustment would leave Mr. Macri little wiggle room to use fiscal policy to juice the country’s contracting economy. Meanwhile, to cut costs, the IMF expects Mr. Macri to reduce sharply the public sector wage bill, which consumed a staggering 12 percent of GDP in 2017, through attrition and a reduction in the real wages of public sector employees (i.e., raises that do not keep up with inflation). This would be a major challenge for Mr. Macri, as public sector unions are combative, aligned with kirchnerismo and offer potential foot soldiers for Mr. Macri’s labor union nemesis, the Moyano family. In these days of austerity, Mr. Macri will have limited resources to negotiate with the unions.

The IMF program also calls for a reduction in infrastructure spending, a government priority and a traditional option for any administration looking to boost economic activity before an election. The IMF expects public-private partnerships to compensate for reduced public spending, which would prevent job losses and pacify the construction workers’ union, a key Macri ally. Indeed, Mr. Macri projects $26 billion in private infrastructure investment in the coming years. But these potential investors will be stung by the IMF deal: The agreement anticipates the suspension of scheduled tax cuts, including export taxes on soy.

Any austerity program is politically costly, but the IMF’s tainted brand in Argentina makes the bailout especially perilous for Mr. Macri. In her public comments, Ms. Lagarde has been exceedingly sensitive to the political realities in Argentina. But the program’s up-front austerity is totally detached from Argentina’s electoral calendar. After all, not only will budget cuts hurt the president’s standing with key constituencies, but the agreement also grants the central bank greater autonomy. Like the budget cuts, that make sense in the long term. But in an election year, central bank independence could lead to persistently high interest rates that further sap economic growth, and limits to the inflation-be-damned peso printing that Argentine leaders typically favor while campaigning.

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Argentina Project

The Argentina Project is the premier institution for policy-relevant research on politics and economics in Argentina. Read more

Explore More in Weekly Asado

Browse Weekly Asado

Dengue Haunts South America’s Summers

Lessons from Costa Rica’s Economic Transformation

Women and Latin America’s Digital Revolution