A blog of the Africa Program

Some Rwandan youth show symptoms of trauma associated with the 1994 genocide despite being born after the traumatic events. Such symptoms suggest that young people have unlived memories haunting their minds, leading them to feel and behave similarly to adults who went through past traumas. How can one make sense of and treat those suffering from unlived traumatic pasts? This is a challenge for the hundreds of thousands of youths with no first-hand memories of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda but are still living in the shadow of trauma etched into the fabric of Rwandan society.

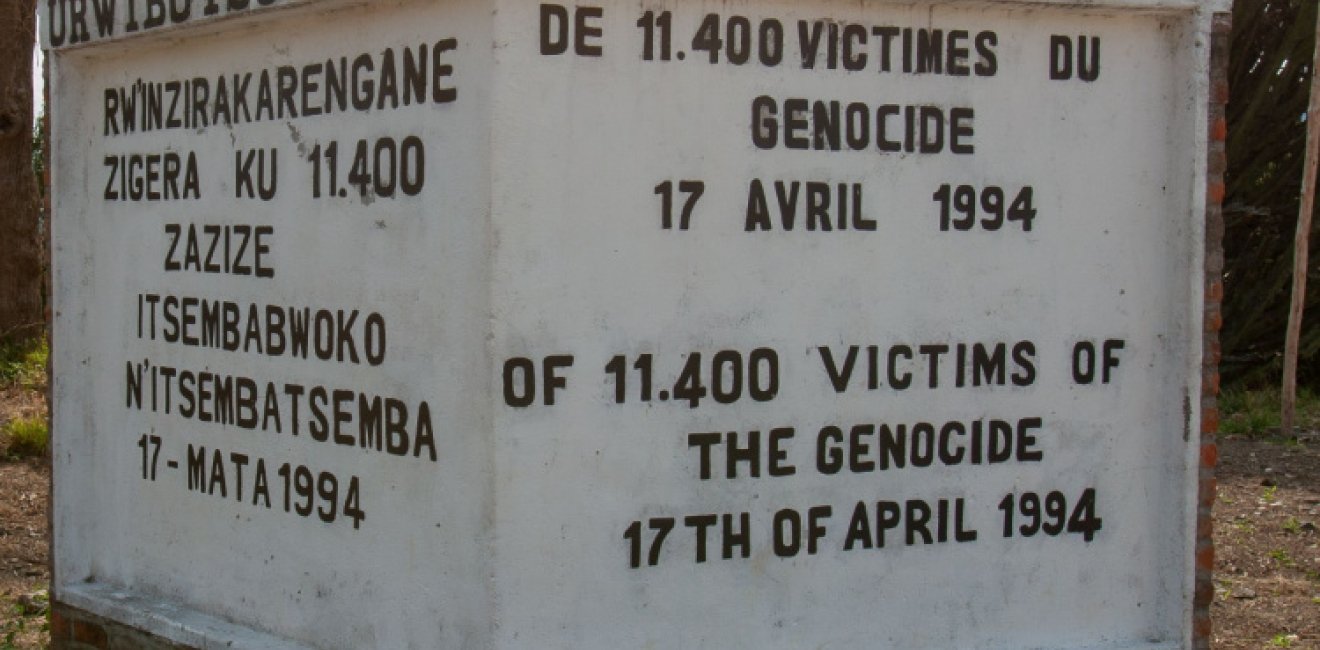

The 1994 genocide in Rwanda took more than one million lives in just 100 days. Those who witnessed the genocide were deeply traumatized by its horrific acts. Even though the genocide happened before many of today’s Rwandan youth were born, the personal experiences of parents, families, and communities continue to breed lasting pain, grief, anger, and disbelief in the generations that have followed. The latter may determine how this generation makes sense of this unlived past, which is crucial for peacebuilding.

Factors to Help Make Sense of Traumatic Memories

Despite the passage of time, family, social, and cultural narratives continue to influence how post-genocide youth interpret and understand the 1994 genocide. Sensemaking is processing the meaning of past, ongoing, and future events. To make sense of the past, younger generations in Rwanda depend on knowledge transmitted through family stories, collective memories, school curricula, and the cultural environment in which they grow. The media, material representations, and symbols found at memorial sites commemorating the genocide also play a pivotal role in shaping the understanding and unlived memories of post-genocide Rwandan youth.

Intergenerational trauma and memory transmission are other means through which post-genocide youth interpret and internalize the events of the 1994 genocide—transmitted emotional and psychological scars from one generation to another influence how younger generations perceive and interpret historical trauma. Moreover, verbal communication of experiences in post-genocide societies, such as oral history and storytelling, strongly impacts the perspectives and cognitive frameworks of post-genocide youth.

Barriers to Rwandan Youth’s Ability to Understand an Unlived Past

Making sense of the dark chapter of violence that continues to mark Rwanda’s identity remains a struggle for younger generations. As mentioned in my previous blog, parental silence, the ability of elders to disclose the horrific details of the past, and efforts to prevent children from developing feelings of hatred or desires for revenge have developed a mindset among older-generation Rwandans that children cannot or should not comprehend that past. Rwandan parents who were perpetrators of the genocide shy away from talking about the past to present a positive image of themselves to avoid shame for themselves and their children. Other parents harbor anger, which prevents them from moving beyond agonizing memories and providing truthful accounts of the traumatic past.

Youth may also struggle to make sense of unlived traumatic pasts due to their perceptions that parents’ experiences are made-up stories. An example from the Cambodian context shows that some parents avoid conveying past experiences to their progeny because they imagine that their children do not believe the genocide memories shared with them through transmitted knowledge. When parents share experiences, their accounts sometimes sound unbelievable to the next generations due to the temporal horizon: youth did not witness the past with their own eyes, and therefore, they cannot understand this past in the same way as those who have directly experienced it. Youth disbelief can lead to denial of the past as history seems implausible. The youth cannot concretely grasp it and imagine such traumatic events being carried out by human beings towards other human beings, especially in their own country and communities.

Discourse about the past could help younger generations learn from history while developing a sense of positive self-identity and ensuring youth develop into adults who will champion the prevention of future violence. However, parents continue to remain silent as disclosing the past brings back painful memories. Consequently, descendants of both genocide survivors and perpetrators develop confusion instead of having a clear sense of what happened during the genocide. The inability to make a clear sense is heightened by incongruities between messages delivered at home, those taught in schools, and those transmitted in public remembrances and communities. As a result, people who suffer from psychological trauma—including Rwandan children who did not live through the genocide—are likely to develop negative perspectives about themselves and the world, which portends the risk of continued violence in Rwanda in the future.

Conclusion

The experiences and perceptions of Rwanda’s post-genocide youth reflect the enduring impact of the 1994 genocide. The inability of older generations to appropriately communicate memories affects Rwandan youth’s ability to make sense of the unlived past, which could cause these memories to disappear from history. Yet, its disappearance may hinder youth from constructing their complete knowledge of the past and affect their identity construction, thus struggling to contribute to a peaceful society in the future. Space and approaches to promote intergenerational communication of the genocidal past memories from older generations to younger ones should be prioritized to facilitate young Rwandans to construct coherent narratives about the past and, thus, their identity. Families, at school, public debates about genocide history, and other settings would enable intergenerational communication of the past. And it is by having enough knowledge about this past that they can participate in the prevention of violent conflicts in the future.

Marie Grace Kagoyire is a Rwandan researcher interested in understanding how young people make sense of the genocide memories as they navigate them in everyday life. She is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Stellenbosch, South Africa. She was a Southern Voices Network for Peacebuilding Scholar for the Fall 2023 term in Washington, DC.

The opinions expressed on this blog are solely those of the authors. They do not reflect the views of the Wilson Center or those of Carnegie Corporation of New York. The Wilson Center’s Africa Program provides a safe space for various perspectives to be shared and discussed on critical issues of importance to both Africa and the United States.

Author

Ph.D. candidate in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, under the Chair for Historical Trauma and Transformation, Stellenbosch University

Africa Program

The Africa Program works to address the most critical issues facing Africa and US-Africa relations, build mutually beneficial US-Africa relations, and enhance knowledge and understanding about Africa in the United States. The Program achieves its mission through in-depth research and analyses, public discussion, working groups, and briefings that bring together policymakers, practitioners, and subject matter experts to analyze and offer practical options for tackling key challenges in Africa and in US-Africa relations. Read more

Explore More in Africa Up Close

Browse Africa Up Close

The Innovative Landscape of African Sovereign Wealth Funds