A blog of the Indo-Pacific Program

Donna Knox never met her father. She was born two months after he disappeared in North Korea in 1952 at age 26, a star collegiate hockey player for the University of Michigan who was the father of a young son and a daughter on the way.

Still, he loomed large in their lives as his wife and children waited for word on his whereabouts.

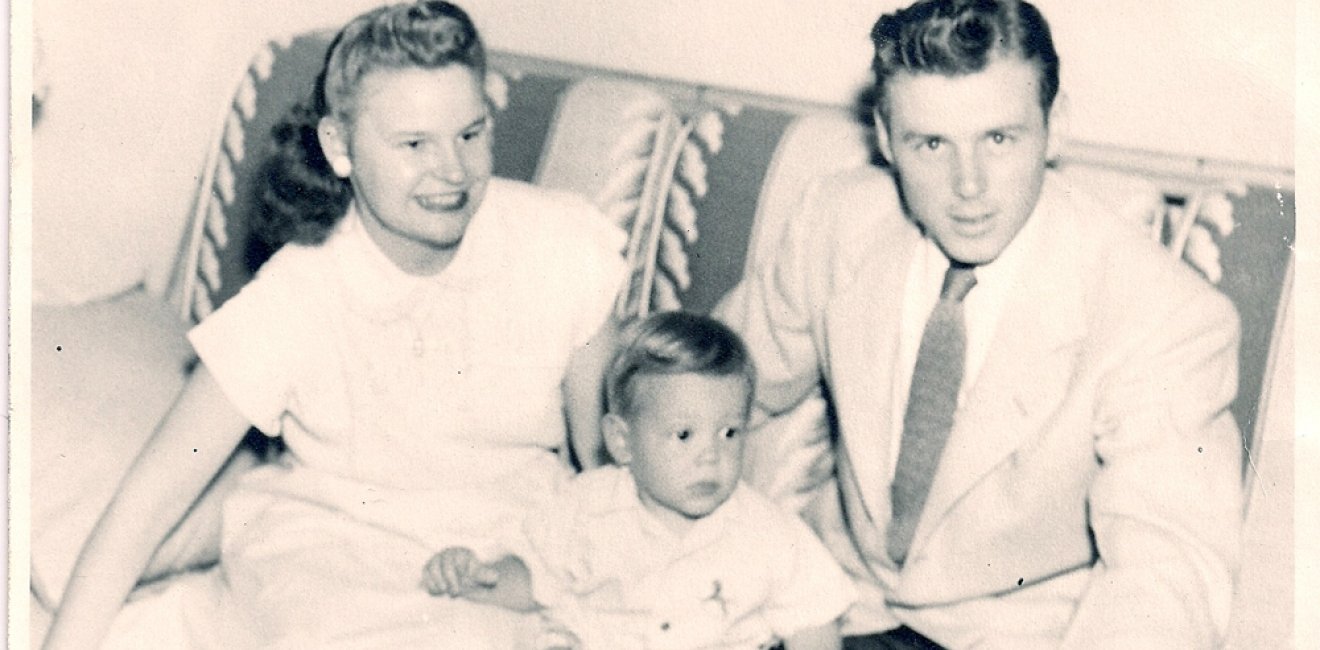

Hal Downes with his son Rick.

Image courtesy of Donna Knox.

“Our mom kept him alive for us,” Knox said recently by phone from her home in Maine. “I have his skates, his jersey, his wallet—every article you can imagine.”

Officially, “he was missing—he wasn’t dead,” she said. “So we kept waiting for him to come home.”

That was more than 65 years ago. Air Force Lt. Hal Downes remains missing in action from the Korean War, along with some 7,700 other American military personnel still unaccounted for decades after the three-year, U.S.-led UN battle against the North Koreans and Chinese for control of the Korean Peninsula.

Returning the remains of U.S. soldiers was among a handful of promises—along with a commitment to denuclearization—that North Korea’s Kim Jong Un made to President Donald Trump when they met in June for a historic summit in Singapore. While the United States and North Korea remain at odds over how to define “the complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula,” Pyongyang has moved forward with its promise to return war remains.

Officially, “he was missing—he wasn’t dead,” she said. “So we kept waiting for him to come home.”

Last week, Defense Department officials flew to the eastern North Korean port city of Wonsan to retrieve 55 sets of remains that the North Koreans say they believe date to the Korean War. The North Koreans could not identify the remains—or even confirm that they were the remains of Americans—and handed over only one set of military dog tags.

Still, 55 caskets draped in the flag of the United Nations were loaded onto a plane in Wonsan and then flown to a U.S. military base in Osan, South Korea. The images of American and North Korean officials working side by side served as a powerful reminder of the need for confidence-building measures between the wartime foes.

Image courtesy of United States Forces Korea Public Affairs.

The caskets came off the plane in Honolulu for DNA analysis draped in U.S. flags. On hand in Hawaii was Knox’s older brother, Rick, who was 3 when his father disappeared. Knox followed news reports of the ceremony.

“I watched them bringing the caskets off the plane, and I had a lump in my throat. It was very moving,” she recalled.

“Halfway through, I stopped to realize that my dad could be one of them,” she said. “I broke down and cried.”

Rick Downes (left) and Donna Knox (right). Photos courtesy of Donna Knox.

For 25 years, Knox and her brother, Rick Downes, have been closely involved with the Coalition of Families of Korean and Cold War POW/MIAs, pressing both U.S. and North Korean officials to push harder on finding and identifying Korean War remains as well as American POWs who were never repatriated.

After fighting for answers for so many years, Knox had forgotten to consider that one of those caskets may contain a clue that could help her find out what happened to her father after his plane went down in North Korea in 1952.

Lt. Hal Downes was a WWII veteran who was called back into the reserves in the spring of 1951. He reported to duty in September 1951, and began flying missions to Korea. On his 11th mission, just before midnight on Jan. 13, 1952, the engine of his B-26 bomber stopped. He was never seen again. His family has no idea if he died that day in the cold, or if he was taken prison and perhaps even spirited to Siberia to work for the Soviets.

Donna Knox is aware that it will be a long and complicated process to identify the newly returned remains—if they’re identified at all.

“One family is going to get a set of dog tags. Dog tags can be right or wrong...but that’s so much more than we used to have.”

“One family is going to get a set of dog tags. Dog tags can be right or wrong,” Knox told me. “But that’s so much more than we used to have.”

Officials may have loaded 55 caskets onto that plane in Wonsan, but there could be many more commingled remains, and some could turn out to be those of soldiers from other countries who fought alongside the Americans on behalf of the UN forces. During a landmark 1990-94 operation to recover U.S. remains, the 208 sets handed over by the North Koreans ended up containing the remains of more than 400 Americans, according to the Defense Department.

Though the technology used to identify remains has improved over the decades, one problem is the lack of detailed accounting from North Korea of the locations of wartime casualties, Knox says. Hundreds of UN warplanes went down across North Korea, particularly during fierce battles in the Jangjin Reservoir, better known in the United States by its Japanese colonial-era name, the Chosin Reservoir.

Like Lt. Downes’ plane, many went down in rice paddies and farming fields, and it’s not clear whether the locals reported finding planes or bodies, and what they did with them. Some bodies were buried in mass graves; many of those buried near rivers were washed downriver by the flooding that besieges North Korea during the summertime rainy season, making it hard for authorities to link the bodies to battles.

The names of some, including Army Cpl. Terrell J. Fuller of Toccoa, Georgia, were on a list provided in December 1951, by China and North Korea, of soldiers who died in their custody. Scientists analyzed DNA, dental and chest X-rays to identify him as one of the men whose remains were returned to the United States in the 1990s.

Fuller was accounted for in April of this year and will be buried in his hometown on Aug. 11. He had been missing since Feb. 12, 1951, and was declared dead in 1954.

Unlike Fuller, Lt. Downes was never declared dead. Their mother says Rick would cling to the front door, crying: “Daddy, Daddy, where are you?” They had one voice recording of their father—singing a song with their mother at a local store recording booth with their strong Massachusetts accents—that they played over and over.

In September 1953, the North Koreans released the Americans who had been held as prisoners of war. Knox says her mother “stood in front of her little TV with rabbit ears and watched the POWs come across the bridge at Panmunjom.”

“When he wasn’t there, she collapsed.”

Eventually, the young mother remarried. But Elinor Hull, now 92, never forgot Hal Downes, the father of her two children.

“She has pictures of him all over her room,” Knox says. “He was the love of her life.”

Follow Jean H. Lee, director of the Hyundai Motor-Korea Foundation Center for Korean History and Public Policy, on Twitter @newsjean. The Coalition of Families is on Twitter as @koreanwarmias.

Images Courtesy of Donna Knox and the U.S. Department of Defense.

The views expressed are the author's alone, and do not represent the views of the U.S. Government or the Wilson Center. Copyright 2018, Asia Program. All rights reserved.

Author

Journalist and former Pyongyang Bureau Chief, Associated Press

Indo-Pacific Program

The Indo-Pacific Program promotes policy debate and intellectual discussions on US interests in the Asia-Pacific as well as political, economic, security, and social issues relating to the world’s most populous and economically dynamic region. Read more

Hyundai Motor-Korea Foundation Center for Korean History and Public Policy

The Center for Korean History and Public Policy was established in 2015 with the generous support of the Hyundai Motor Company and the Korea Foundation to provide a coherent, long-term platform for improving historical understanding of Korea and informing the public policy debate on the Korean peninsula in the United States and beyond. Read more