A blog of the Indo-Pacific Program

North Korea has persistently refused to negotiate on the issue of denuclearization with the United States since the breakdown of the second summit at Hanoi in February last year and working-level negotiations at Stockholm in October. At the same time, it has continued to develop its nuclear weapons and ballistic missile capability.

Given this context, the result of the upcoming U.S. presidential election is expected to have a significant impact on North Korea policy going forward.

Return to summits under Trump?

If President Donald Trump is reelected, he will seek to jumpstart negotiations using the approach we saw in 2018 and 2019: a top-down, summitry-led process of direct meetings between himself and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

However, the breakup of his second meeting with Kim, in Hanoi in February 2019, demonstrates how summits held without sufficient prior preparation through sustained working-level negotiations are likely to end in failure. At the same time, the experience of working-level talks at Stockholm in October 2019 between the United States and North Korea confirmed just how progress on the nuclear issue is difficult to achieve.

At present, North Korea has said it will not participate even in working-level negotiations unless the United States ends its “hostile policy.”

Thus, if President Trump wins reelection, he may consider prioritizing the largely symbolic demonstration of ending the “hostile policy” through measures that improve relations.

Such measures could potentially include the posting of diplomats at liaison offices in each other’s respective capitals that would function as de facto embassies. Liaison offices or interest sections have previously played the role of transitional institutions in U.S. relations with hostile states, and have helped to resolve conflicts and build trust.

But for North Korea, there is no guarantee that opening liaison offices would ultimately lead to a normalization in relations with the United States, and the actual gains from such a move are not that large. Hence, there may be limited interest in Pyongyang in such proposals. Additionally, if the coronavirus pandemic continues, North Korea may remain passive to interaction with the United States to ensure limit the potential entry of COVID-19 into the North.

Big changes under Biden

If former Vice President Joseph Biden wins, we can expect big changes in U.S.-North Korea policy.

Biden has indicated that efforts would be redirected toward working-level negotiations and to prioritize international coordination in order to develop a concrete agreement before proceeding with another U.S.-North Korea summit.

“Fewer summits, tighter sanctions, same standoff,” Reuters summed up in August.

If Biden is elected president, it appears likely that Washington’s North Korea policy will become tougher than current Trump Administration policy.

In November 2019, Biden declared: “There will be no love letters in a Biden Administration.” A month later, in response to the question “Would you continue the personal diplomacy President Trump began with Kim Jong-un?” from the New York Times, he said “No.”

The New York Times also asked: “Would you tighten sanctions until North Korea has given up all of its nuclear and missile programs?” and he responded “Yes.”

The New York Times also asked: “Would you tighten sanctions until North Korea has given up all of its nuclear and missile programs?” and he responded “Yes.” He also said he would consider using military force, but “force must be used judiciously to protect a vital interest of the United States, only when the objective is clear and achievable, with the informed consent of the American people, and where required, the approval of Congress.”

Biden has consistently stuck to the view that a summit with Kim would only be possible if certain conditions were met. In a Washington Post survey of Democratic presidential published in September 2019, Biden said he would continue with Trump-style direct meetings with the North Korean leader even without substantial concessions toward denuclearization − only if “North Korea satisfies certain conditions.”

Similarly, in a January 2020 Democratic Party presidential debate, Biden said he would not meet Kim Jong Un without preconditions.

He said that by meeting with Kim, President Trump had given the North Korean leader “legitimacy and weakened the sanctions we have against them.” He pledged to strengthen relations with South Korea and Japan, while “putting pressure on China to put pressure on [North] Korea to cease and desist” their nuclear program.

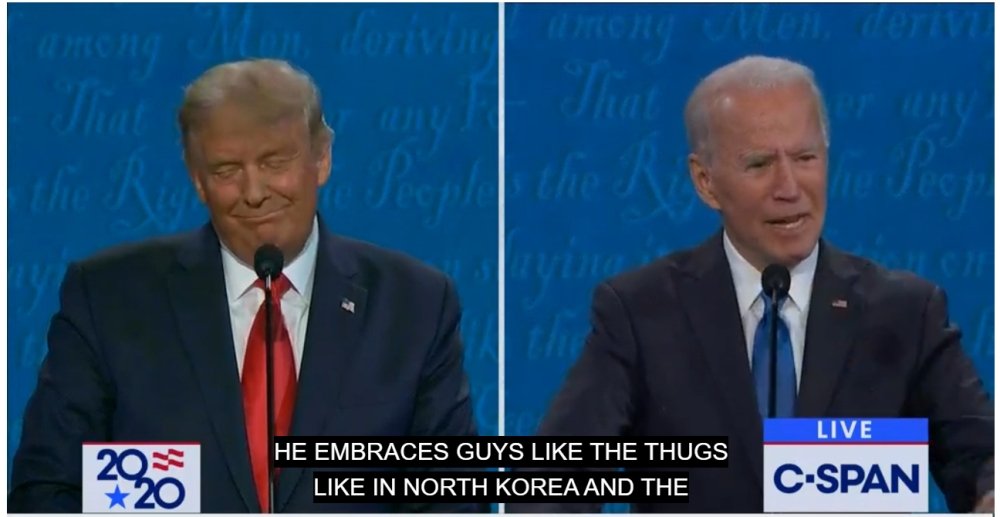

And during the Oct. 22 presidential debate, Biden said he would only meet with Kim Jong Un on the condition that “[he] agrees to draw down his nuclear capacity.”

Biden’s apparent skepticism toward a summit with Kim stems fundamentally from his view of Kim as a “dictator,” “tyrant,” “butcher” and “thug.” While campaigning in Iowa, Biden criticized Trump Administration policy, saying: “We are embracing thugs like Putin and Kim Jong Un.”

“This president's talking about love letters with a butcher,” he said, referring to Kim. “This guy had his uncle's brains blown out sitting across the table, his brother assassinated in an airport. This is a guy who has virtually no social redeeming value.”

In November 2019, the Korean Central News Agency responded to Biden’s remarks with characteristically colorful language: “A rabid dog in the US has another fit of spasm, being greedy for power. … Rabid dogs like Biden can hurt lots of people if they are allowed to run about. They must be beaten to death with a stick, before it is too late.”

A spokesman for the Biden campaign responded: “It’s becoming more and more obvious that repugnant dictators, as well as those who admire and ‘love’ them, find Joe Biden threatening.”

In his August 2020 speech accepting the Democratic nomination, Biden said: “The days of cozying up to dictators" were over. In the second Presidential Debate, he also referred again to Kim Jong Un as a “thug.”

Clearly, if Biden wins, he will take a skeptical attitude toward negotiations with North Korea and would likely rely on pressure and even stronger sanctions.

It could take six months for the Biden Administration to assemble a new foreign policy and security team and to establish the new direction of North Korea. Negotiations with the North Korea could be expected to begin in the latter half of next year at the earliest.

Given that South Korea’s next presidential election is scheduled for March 2022, the latter half of 2021 will be right when South Korean politics enters full-scale campaign mode. This may weaken the potential policy momentum of the Moon Administration in Seoul.

In the meantime, there is real risk that North Korea will have further developed its nuclear weapons and missile capabilities, and denuclearization will be a yet more difficult goal to realize.

Therefore, it would be best if a potential Biden Administration moves quickly to minimize the gap in negotiations with North Korea through closer cooperation with Seoul.

Biden has previously stressed the role of close cooperation with allies South Korea and Japan and pressuring China in resolving the North Korean nuclear issue. This is a good sign.

“After three made-for-TV summits, we still don't have a single concrete commitment from North Korea,” he told the Washington Post in September 2019. “If anything, the situation has gotten worse.

“As president, I will empower our negotiators and jumpstart a sustained, coordinated campaign with our allies and others – including China – to advance our shared objective of a denuclearized North Korea,” he said.

In response to New York Times questions for candidates in December 2019, Biden said: “I would work with our allies and partners to prevent North Korea's proliferation of nuclear weapons to bad actors… And I would insist that China join us in pressuring Pyongyang.”

China’s role

The single most important reason why North Korea currently refuses to negotiate with the United States on denuclearization is that it believes it can develop its economy through cooperation with China, without giving up its nuclear weapons.

Thus, if the U.S. government is unable to get active cooperation from China on the North Korean nuclear issue, it will struggle to succeed in negotiations with the North, regardless of proposals it puts on the table.

North Korea can refuse to negotiate with the United States, but given its need to cooperate with China to survive, North Korea would struggle to refuse to participate in talks if China is involved.

Summits and working-level talks involving the United States, China, and the two Koreas through a “four-party talks” framework are essential to ensuring that China is actively involved in the process of denuclearization and the issue of reciprocal measures. North Korea can refuse to negotiate with the United States, but given its need to cooperate with China to survive, North Korea would struggle to refuse to participate in talks if China is involved.

If four-party talks are held, a comprehensive range of issues, including denuclearization, a peace treaty, security for the North, sanctions relief and normalizing relations between Washington and Pyongyang, can all be discussed. If such talks happen, we can hope for actual progress on the nuclear issue.

Strategic competition between the United States and China limits the potential for Washington to cooperate with Beijing on the North Korea issue. Yet, China wants North Korean denuclearization, too. Hence, if a creative and rational alternative with respect to denuclearization and the international response is put forward by the United States in close cooperation with South Korea, then China can be expected to cooperate for the stability of the region. Regardless of who wins in November, it will soon be time to move beyond the current bilateral framework for negotiations on the nuclear issue, and to actively engage with China in the process.

Chinese cooperation is the biggest issue in the North Korean denuclearization process.

If four-party talks begin and should they result in real progress, then it will come time to expand them further to include Russia and Japan in a reconstituted six-party talk framework.

This will allow for the prospect of normalization of relations between Pyongyang and Tokyo, adding further pressure to North Korea to push forward decisively with denuclearization.

Seong-Chang CHEONG is a fellow at the Wilson Center’s Hyundai Motor-Korea Foundation Center for Korean History and Public Policy and is a senior research fellow at the Sejong Institute in the Republic of Korea (South Korea).

The views expressed are the author's alone, and do not represent the views of the U.S. Government or the Wilson Center. Copyright 2020, Asia Program. All rights reserved.

Author

Senior Research Fellow, The Sejong Institute, South Korea

Indo-Pacific Program

The Indo-Pacific Program promotes policy debate and intellectual discussions on US interests in the Asia-Pacific as well as political, economic, security, and social issues relating to the world’s most populous and economically dynamic region. Read more

Hyundai Motor-Korea Foundation Center for Korean History and Public Policy

The Center for Korean History and Public Policy was established in 2015 with the generous support of the Hyundai Motor Company and the Korea Foundation to provide a coherent, long-term platform for improving historical understanding of Korea and informing the public policy debate on the Korean peninsula in the United States and beyond. Read more