China, Latin America, and the United States: The New Triangle

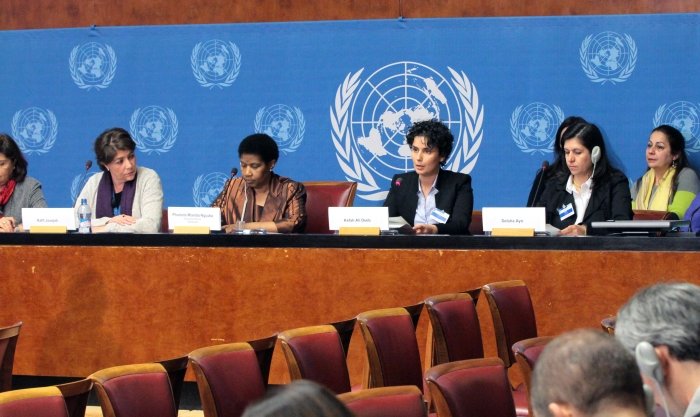

On May 26, 2010, the Latin American Program, the Institute of the Americas, and the Institute for Latin American Studies of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences held a conference to explore the dynamics of the China-Latin America relationship, as well as the implications for the United States of China's growing economic and political presence in the Western hemisphere.

An Overview of the China-Latin America RelationshipIn a keynote address, Enrique García, president and CEO of the Andean Development Corporation (CAF), a Latin American development bank, indicated that despite last year's economic downturn, the global economic crisis has not obstructed Latin America's path toward sustained economic growth, macroeconomic stability, and positive external balances. According to García, the region is projected to grow by 4.5 percent over the next year, with some countries by as much as 7-8 percent. This is partially due to the implementation of conservative fiscal and monetary policies, continued central bank independence, and strict financial regulations.

García warned that despite the benefits of high export prices, the concentration of exports to China in specific areas, such as soya, raw materials, and minerals, makes Latin America vulnerable to an economic downturn and reinforces its traditional production structures. In order to create more equitably distributed, sustainable growth, the China-Latin America trade model must move beyond free trade agreements. However, current levels of Chinese foreign direct investment in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) are low, and most is targeted at the tax havens. The fundamental questions for the China-Latin American relationship, he said, are how to improve trade quality and how to diversify direct investment beyond raw materials.

What a Growing China Means for Latin America's EconomiesProfessor Chai Yu of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences stated that China's development model is unique in that GDP growth is driven by consumption, foreign and domestic investment, and to a lesser extent, exports. Between 1993 and 2009, the majority of China's imports and exports, 59.9 percent and 46.5 percent, respectively, were with trading partners in Asia; Latin America only accounted for 6.9 percent of China's imports and 5 percent of its exports. Brazil and Chile have been the principal Latin American beneficiaries of Chinese growth.

Nonetheless, Yu explained that China is attempting to make the results of economic development felt more broadly by its population through "inclusive" development, which she viewed as an opportunity to promote a stronger relationship with Latin America. She suggested that with increased cooperation, China and Latin America's relationship could parallel that of China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), whose size of membership in the early 1990s and concerns about China's economic development were similar to that of Latin America today.Ambassador Sergio Ley, Mexico's former ambassador to China, outlined historical links between China and Mexico. Latin American conquistadores first transported Chinese silks, porcelain, teas, and spices through Pacific Ocean ports and Mexico en route to Spain, where the goods were purchased using Mexican silver. Centuries later, China and Mexico's relationship was challenged by the Mexican financial crisis in the 1980s. Subsequently, Mexico began to implement protectionist measures in response to the proliferation of cheap Chinese products in the Mexican market. From the Chinese perspective, the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement and the delayed Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with China represented a realignment of Mexico's interests away from China. Indeed, Mexican businesses were duly concerned with the effect that competition would have on Mexican development. However, trade between the two countries continued to grow and by 2009, Ley said, Mexico was China's largest trading partner in Latin America and China was Mexico's second largest trading partner.

Nonetheless, the specific dynamics of the China-Mexico economic relationship reveal certain imbalances and challenges. While Mexican imports from China totaled $32.5 billion in 2009, exports to China from Mexico measured only $3.9 billion. In addition, China has become one of Mexico's main competitors in the U.S. market. To address this, Ley suggested structural economic reforms, Chinese investment in the Mexican manufacturing sector, and continued attempts to increase Mexican exports to China.According to Mauricio Mesquita Moreira of the Inter-American Development Bank, China played an important stabilizing role in Latin America and the Caribbean during the recent global financial crisis. As the world's exports fell in 2009, LAC's exports to China grew. Moreira posited that this export growth boom, largely composed of natural resources, was partially due to China's internal resource constraints and obstacles within the WTO accession process. The complementarities between China and LAC are evident: if China grows by 10 percent, the demand for LAC exports grows by 25 percent. The downside is that the benefits of this trade are not evenly distributed across the region; Chile, Peru, Brazil, Argentina, and Costa Rica make up a demonstrably larger share of exports to China than other LAC countries.

Further, Moreira echoed prior panelists in noting the disparity between the massive trade between China and LAC, and the small amount of Chinese FDI in the region. In 2008, total Chinese FDI to the region (excluding tax havens) was $48.9 million, paling in comparison to Latin American's overall FDI of $122 billion. Between 2001 and 2009, China's cumulative FDI to Brazil was $172.7 million, a significantly smaller sum than Japan and Korea's FDI inflows of $9,344.63 million and $793.98 million, respectively.

In the face of China's massive labor market and cheap wages, Moreira suggested that Brazil and Mexico capitalize on their low-wage areas in the northeast and south. LAC countries should increase their productivity, and in the case of Mexico and Central America, use their comparative advantage of proximity to the United States to focus on goods that are time sensitive and require "speed to market." He also noted a "market failure" in which 90 percent of the final costs of goods shipped to China are freight costs that do not go to the country of origin, but to the shipping companies; this inefficiency could be an opportunity for LAC countries to extract higher rents from the natural resources it exports to China.Nelson Cunningham of McLarty Associates argued that from a strategic perspective, China's interests appear to be purely commercial; this is unlike Russia's ideologically-based military and diplomatic alliance with Venezuela, which he viewed as a means to balance U.S. influence in Latin America. However, on Latin America's part, the partnership may have indeed been initiated to serve as a "strategic counterweight" to the region dependence on the United States; twelve years ago, China accounted for only 4 percent to 6 percent of Latin American trade, but is now a top trading partner for many countries in the region. Nonetheless, the relationship has not necessarily fulfilled these expectations. For example, popular accusations have been leveled against Brazilian President Lula da Silva that China took advantage of him through both the commercial arrangements between the two countries and in negotiations over China's accession to the WTO.

Building a strategic relationship with China is challenging not only because of low levels of Chinese investment in the region, but also because the investment that does occur generally employs Chinese laborers and materials brought over for specific infrastructure projects. In addition, the China-Latin America relationship lacks the deep cultural kinship that exists between Latin America and the United States and Europe. Within this context, Cunningham posited that the relationship between China and Latin America will remain strictly commercial, but recommended for the United States to be vigilant that the partnership not become political. In order for the United States to maintain its privileged relationship with the region, it must compete with China commercially by lowering trade barriers to Latin American exports and expanding preexisting commercial and corporate ties.

China and Latin America: Political and Economic Partners, or Competitors?

"Are we looking at China and Latin America oil as [a] panda or a dragon?" asked Jeremy Martin, director of the Energy Program at the Institute of the Americas. Estimates project that China's demand for oil will grow from 8 million barrels per day (mbd) to 16 mbd by 2030; current imports as a percentage of consumption are over 50 percent. Beijing's general strategy for satisfying Chinese demand consists of securing access to a diverse array of material reserves and inserting themselves into production positions in oil projects. Despite its ready economic capital, China must face increased competition for oil resources in today's world where there are few easy targets.

As a result of the failed and conflictive U.S. (Union Oil Company of California, or UNOCAL) and Ecuador (Andes Petroleum Ecuador Ltd.) acquisitions in 2005, China has learned that it can no longer "go it alone" in the Western hemisphere. China's strategy now includes mergers and acquisitions (M &A) through the purchase of local shares, joint ventures with local companies, and oil swaps, where long-term credit is exchanged for oil. According to Martin, oil swaps are becoming the "most important arrows in Beijing's quiver." This is exemplified by a Venezuela's recent agreement with the Chinese Development Bank to receive a $20 billion credit line that can be repaid in oil. Brazil has negotiated a similar $10 billion credit line that will provide Petrobras with a portion of the massive capital needed to develop its recently discovered pre-salt deep sea fields. In closing, Martin warned against overstating the current energy relationship between China and Latin America, noting that while a $10 billion oil swap for Brazil may sound considerable, it is less than 20 percent of Petrobras' annual capital expenditure program of $47-50 billion.

Dr. Sun Hongbo of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences pointed to strong Chinese economic growth, national oil companies, government, and financial organizations—especially the Chinese Development bank—as the four elements driving Chinese energy cooperation with Latin America. A new trend emerging from this mix is the increased cooperation between financial organizations and national oil companies. Sun listed five models that China employs for cooperation: 1) a technical service model, 2) a joint development model, 3) an infrastructure-building participation model, 4) a loans for oil model, and 5) a bio-fuels technology joint research model. These models can be seen across various countries with which China is cooperating.

For example, in Mexico, Chinese companies had provided nearly $1 billion in engineering services for oil projects by the end of 2007. Sun also cited successful joint ventures in Colombia and Ecuador—including the Andes Petroleum purchase of all of Encana's assets in Ecuador—as areas of successful cooperation. In addition to the China-Brazil loan-for-oil agreement, China will also cooperate with Brazil in the development of renewable energy sources such as biofuels. However, given that Latin America only accounted for 7.58 percent of China's oil imports in 2008, Sun doubted that Latin America would play a strategic role in guaranteeing China's future energy security. While opportunities for growth and investment are present for both China and Latin America, China's national oil companies are confronting risks of social conflict at the local level, political instability, intense competition, environmental clauses, transportation costs, and the uncertain U.S. response to China's presence in the region. Sun also pointed out that Latin America can still be viewed as a strategic alternative for China to diversify its oil importing.Philip Yang, Petra Energia Brazil, offered three propositions for understanding the substance and implications of China's energy plans in Latin America.

First, he asserted that China's oil policy is the facet of China's energy policy which is likely to have significant implications for Latin America. According to Yang, China's growing oil demand and the country's reliance on oil imports is what matters most to Latin American countries. This is for three reasons:

1. Latin America and Brazil in particular constitute one of the world's most successful oil exploration frontiers;

2. China is hungry for oil and emerges as a global source of FDI;

3. The oil industry is one of the few in the energy sector that is not site specific.

Second, Yang stated that despite of the potential for a dynamic interaction between China and Latin America in the realm of the oil industry, the Chinese presence in Latin America and especially in Brazil is very meager. For example, China's FDI (non-bond investment) in Latin America accounts for only 1 percent of China's total investment stock.

Yang set forth three possible explanations for China's overwhelming presence in exploration and production in Africa and its near absence in Latin America.

1. For foreign countries, China uses a "confidence-building ladder approach" in the order of trade, services, and then investment. Trade data between China and Latin America supports this hypothesis: trade flows grew dramatically, and then services also increased, but to a much lesser extent and only in a few countries. The third step of the ladder – investment – is yet to come for Latin America because it hasn't reached the level of total confidence for China to invest in the region.

2. China has a clear investment preference targeted to only two types of destinations:

(a) High trust societies, where the rule of law prevails with clarity; and

(b) societies with a "loose" regulatory framework

This hypothesis would explain, for example, the strong priority that the Chinese are giving to a country such as Australia—the top destination of China's OFDI in 2009—as well as China's widespread presence in Africa.

3. The third explanation has to do with political motives. Chinese NOCs would combine their oil interests with political and strategic influence.

Finally, Yang referred to what he called "the untold story": that Brazil's onshore oil production potential was totally abandoned. The staggering success of the offshore reserves overshadowed and continues to overshadow the vast onshore potential. This helps explains the current absence of China in Brazil. He stressed that from 1953 to 1998, Petrobras held a monopoly. Because it assigned the bulk of its budget and its best thinkers to deepwater exploration, there was simply no one else to undertake onshore exploration.

Yang indicated that with modern geological and geophysical tools, Brazil's onshore potential constitutes a new great oil and gas exploration frontier. The potential for hydrocarbons in Brazil's onshore deposits may present an order of magnitude similar to that of the pre-salt, and with much less risk. China and the United States could play an important historic role in this development.Cynthia Sanborn of Lima, Peru's Universidad del Pacífico situated the presence of Chinese state-owned firms in Latin America in the context of the region's still fragile political democracies. These democracies are characterized by an increased concern for industry diversification, changing roles for the state and political institutions, and the presence of new actors such as global NGOs, the Catholic Church, indigenous communities, and environmental organizations that demand a voice in natural resource policy.

In the case of Peru, mineral exploitation accounts for one-fourth of tax revenues and six percent of GDP—although in some regions it is much higher—and thirty-four percent of mineral investments are from China. While Peruvian governments have a strong desire to attract Chinese investment and increase private development of its industries, national authorities have been largely unable to provide an effective regulatory framework for foreign firms or mediate between these firms and the communities where mineral extraction will occur. As a result, the Chinese have had to learn to implement community relations at the local level and deal with conflicts as they rise.

For example, Chinalco, a major Chinese state owned enterprise, hired experts and local staff with extensive knowledge of community relations; committed to investing in environmental clean-up; and cultivated relationships with local authorities in order to undertake a large copper project in the Junin region. In addition, the company is negotiating compensation to local residents for voluntarily relocating in order to accommodate the open pit mine they plan to build. Sanborn concluded that both responsible national policy makers and effective civil society actors are necessary for mitigating the development impacts of mineral extraction and preventing social conflict. Absent this oversight, local communities must rely on the voluntary and often volatile action by firms themselves.

Hosted By

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more