Environmental Equity in China

The Great Proletariat Revolution, which led to the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949, was designed to rid the country of inequities that existed for over 2,000 years of dynastic rule. Mao Zedong envisioned building a strong, egalitarian utopia to benefit the country's downtrodden peasants and workers. While this "utopia" was rocked with disastrous political and development campaigns, the centrally planned economy with guaranteed jobs for urbanites and some subsidies for rural agriculture brought some economic equality to China—today many joke that under Mao's rule everyone was equally poor. When Deng Xiaoping launched reforms to revitalize China's economy in 1979, he, like Mao, wished to make China strong and stable. While his reforms, and those continued by his successors, have fueled a booming economy, the growth has left many behind—coastal regions flourish, but inland areas have stagnant economies; urban centers are beginning to resemble modern Western metropolises, whereas many rural inland areas are still as bucolic as 30 years ago. The government has attempted to address this widespread economic inequality through policies and campaigns to offer relief for those who have "fallen behind" in the economic boom. Stimulating more economic growth in the inland regions and rebuilding new social safety nets have been central strategies for poverty alleviation.

Another "inequality" stemming from China's long economic boom has been the asymmetrical impact of environmental degradation on certain regions and sectors of the population. The government has responded to serious environmental problems by strengthening previous pollution control and conservation legislation and welcoming international assistance to help solve some of the country's more intractable environmental problems. Paralleling the growth in international environmental nongovernmental organization (NGO) projects in China has been an explosion of domestic green groups. Ultimately, the success of these laws, investments, and activism to mitigate China's environmental problems will depend on whether they give all stakeholders a voice in designing and implementing the solutions.

In 2003, the China Environment Forum, University of Maryland, and University of Duisburg-Essen (Germany) joined together in the Tamaki Environmental Project, in which environmental experts from China, Germany, Japan, and the United States have been exploring the myriad issues associated with environmental equity in China. The research presented at these workshops (to be published in an upcoming book) focused primarily on issues relating to participatory equity (Who has an opportunity to voice their concerns about environmental problems in China?) and procedural equity (What are the institutions and processes that grant or limit access to environmental decision-making?). In addition to examining whether citizens are empowered to voice concern or influence the policy process regarding environmental threats, some participants in this project are investigating issues of regional environmental inequities in China.

At a pair of meetings held at the Woodrow Wilson Center, speakers discussed issues crucial to understanding the complexities of equity and China's environment: Jennifer Turner and Timothy Hildebrandt outlined legal opportunities and impediments for pollution victims to access information and pursue justice; Anna Brettell offered a look at options for citizens to voice pollution complaints and to be heard in the courts; Li Lailai discussed the growing role of the domestic NGO community to assure greater participatory equity; Fengshi Wu presented the unique role of government-organized NGOs (GONGOs) in enabling greater voice in shaping environmental policies; Wen Bo spoke about the currently small, yet important activities of community groups throughout China to spark grassroots activism; Aster Zhang discussed the regional inequities through the lens of conflicts between animal protection and poverty alleviation; and Andreas Oberheitman offered evidence of growing environmental inequities among different regions in energy use and production.

Legislative Obstacles and Opportunities

Along with recent legislation designed to stop environmental degradation, the Chinese government has provided some opportunities for citizens to voice their environmental concerns and assure greater participatory equity. As early as 1979 in the Environmental Protection Act, and more recently in 2003 in the Environmental Impact Assessment Law, the government has included language that in theory offers the public a role in affecting policy or airing grievances. However, according to Jennifer Turner, these laws lack special provisions to guarantee the public is heard. In hopes of increasing citizen voice in the environmental sphere, some multi- and bi-lateral organizations have integrated public participation components into their environmental projects in China: The World Bank requires citizen comment in all of its projects, while the U.S. EPA mandates that cities involved in its air quality monitoring network keep citizens informed on daily air quality—such information used to be viewed as a state secret.The nongovernmental sector is also committed to promoting public participation in China. International NGOs like Oxfam America and professional organizations such as the American Bar Association are expressly devoted to involving the public in their environmental projects. Even more importantly, the fledgling domestic NGO community is leading the charge in China to keep the public keenly aware and involved in environmental issues. Turner pointed out that most Chinese and international NGO initiatives promote information dissemination and public participation. For example, many NGOs regularly involve local communities in on-the-ground conservation projects, while others mobilize even greater numbers in mass environmental campaigns.

Despite favorable legislation and the work of NGOs in China, there are some major impediments to greater participatory equity in China. Timothy Hildebrandt noted that while local governments are often required to involve the public, they are reluctant to do so. Since the cadre promotion system is still closely tied to economic progress—not environmental sustainability—local officials are reluctant to pass along environmental information that might hurt an important industry, the local economy, and ultimately their professional future. Though some legislation in theory allows for the public to engage in environmental issues, they are often unable to do so because of the difficulty of accessing information. Most notably, the 1988 "Law of Keeping State Secrets" essentially makes all information a secret unless the government explicitly indicates otherwise.

It is common for the public to be under-informed about pertinent pollution or natural resource degradation issues. While environmental reporting is growing considerably within the Chinese news media, the government is often wary of disseminating negative environmental information. Thus, self-censorship in the news media also contributes to a dearth of information on some more sensitive environmental issues. Likewise, because of the secret status of much information, citizens are unable to access it themselves. Hildebrandt suggested that an appropriate resolution to this problem is not a broad, and potentially problematic, U.S.-styled Freedom of Information Act. Rather, the Chinese government might be more willing to adopt a EU-styled environmental right-to-know legislation that assures access to environment-related information and also helps guarantee legal remedies to resolve problems.

Going to the Courts

Anna Brettell related several stories of the early years of the People's Republic of China when pollution victims had few options to air grievances. While rare, during Mao's rule citizens sometimes protested severe pollution problems when all other means for recourse were exhausted. In one case, a group of villagers upset with a polluting shipping industry stormed a pier and destroyed loading equipment. These vigilante residents were imprisoned as "counter-revolutionaries" and it took the intervention of the politburo many years later for the villagers to be released. Memories of such harsh punishments led most to fear voicing any grievances. Since the early 1990s, however, Brettell noted that pollution victims in China are increasingly afforded the opportunity to legally register disputes with the government. As a consequence, previously disenfranchised citizens in China have been given greater procedural equity in resolving environmental problems.

Not surprisingly, as the economy has grown, so have pollution problems and the number of environmental complaints. Economic growth has sparked an industrialization boom in cities and rural areas. Over 50 percent of China's air and water pollution stem from small and medium enterprises located in rural areas. While urban areas have cleaned up many polluting industries, the explosion of private car ownership in big cities has made auto exhaust the leading polluter in China's cities. Thus, few Chinese citizens are immune from the impacts of pollution. Although rising incomes have enabled some pollution victims to pursue legal recourse in courts, affording and navigating through the court system has been difficult for most suffering damages from pollution. However, the situation is gradually improving for pollution victims.

Reforms in China's legal system in the early 1990s are at the heart of empowering pollution victims. Brettell noted that before reforms, courts would form a single team to investigate disputes. The team's decision, often biased towards protecting local economic interests, would usually be definitive, limiting the rights of plaintiffs to offer contradictory evidence. After legal reforms, the defendant and plaintiff, not the court, form two investigative teams. Legal battles are now more contentious but the playing field has been leveled somewhat between plaintiffs and defendants. In addition, prior to 1992, the entire burden of proof in pollution victim cases was placed on the plaintiff. However, today if the defendants deny the claim, they are liable to prove their innocence.The government has established more rights for pollution victims to be compensated and attempted to make polluting industries liable. However, China's courts do not have a systematic standard for setting compensation for victims and, more seriously, lack tools to force compensation payment. Moreover, while the legal system has been given more power, courts are still susceptible to intervention and pressure by the local party and government on behalf of polluting industries. Nevertheless, Brettell suggested that authorities have become far more responsive to citizens—particularly in well-publicized cases where there is a high level intervention in support of victims' rights. The government's heightened awareness of pollution victims is in large part a consequence of citizen groups and the news media publicizing the growing inequalities in suffering caused by pollution and local collusion to deny pollution victims their rights for compensation.

Bottom-Up Opportunities for Voice

Citizen groups and NGOs are indeed making their voice heard on environmental problems in China. According to Li Lailai, the growing number of environmental NGOs is evidence of the increasing demand-side institutional change in China. In other words, the growth of NGOs is in large part caused by a void left as new institutional arrangements have emerged in China; many social services once provided by the government are increasingly being eliminated, leaving a great vacancy for social groups to fill the gap. Moreover, China's leadership did not foresee today's serious environmental problems and the fragmented, top-down central government agencies struggle to enforce laws dealing with the complex challenges of pollution and natural resource degradation. Poor enforcement of environmental laws has meant environmental problems are perhaps one of the biggest instances of inequity in Chinese society. However, Li argued that NGOs could help assure greater environmental equity for all Chinese by helping the government improve environmental protection work and more importantly by serving as a bridge between the people and government.NGOs in China take two primary approaches to environmental work—either advocacy or policy research and project activities. Advocacy groups organize mass campaigns, educate the public about environmental programs, and mobilize interested citizens to work for change and appeal to the government. These initiatives may seem somewhat superficial in nature, however they provide a great service to citizens by pushing environmental issues to a more prominent position in the news media and serving to increase options for public participation. What is more, such advocacy and education projects increase public awareness and approval of NGOs in general. On the other end of the spectrum are groups involved in research and project development. These NGOs shy away from mass campaigns and instead devote their energy to working with local officials and communities on projects designed to solve specific environmental problems. For example, the Beijing-based South-North Institute for Sustainable Development has worked with local governments and banks to provide loans for farmers to construct biogas greenhouses. Li Lailai's NGO, the Institute for Environment and Development (IED) has helped the UK's Department for International Development (DFID) on a corporate social responsibility project in Liaoning and Sichuan provinces. IED acted as a liaison to help DFID consultants and the small and medium enterprise managers develop plans for better production and improved communication with local communities.

While NGOs are making a concerted effort to fill the void left by the downsized government and assure equity for all Chinese citizens, they face great challenges in their work. Most notably, Li pointed to the difficulty of legally registering NGOs with the Ministry of Civil Affairs. The small and new NGOs also struggle with securing operational funds, suffer from a strikingly high staff turnover rate, often lack credibility in the public's eye. Consequently, the survival rate of many NGOs is quite low. Li recently spoke with a government official charged with registering NGOs who reported that 70 percent of the groups he registers would not survive even a year.

Despite these limitations, Li maintained that NGOs in China are making important, albeit small, impacts on environmental and social problems in the country. Green NGOs are making a significant contribution to the maturing Chinese political system and burgeoning civil society. Li is optimistic about green NGOs in China, for many are led by charismatic, educated, and well-connected individuals who should serve the groups well and assure expansion in coming years. She feels there is great room for NGOs to develop even further, moving beyond their original charge to address more pressing issues that are not being dealt with by the government. Her optimism is supported by individuals in the Chinese government who recognize the important role that NGOs can play in society. Li recounted a conversation with Xie Zhenhua, minister of China's State Environmental Protection Administration, in which he implored her to keep "making noise" so he could "make noise" to other central government leaders—Minister Xie made a similar plea at a 12 December 2003 meeting of the China Environment Forum.

GONGOs Broadening the Voice in Shaping Policy

In addition to the growth of independent green NGOs, the expansion of environmental government-organized nongovernmental organizations (GONGOs) is another indication of significant institutional change in China. Since the early 1990s, various campaigns to downsize the government have led agencies to off-load employees into newly created research centers or GONGOs. Such entities have helped the government carry out research and pilot projects. For example, though China's State Environmental Protection Administration (SEPA) is charged with overseeing most environmental policies, with its limited number of employees, SEPA has had to depend on its various GONGOs and research centers for assistance.

As quasi-governmental organizations only partially dependent on state resources, GONGOs are often able to able to serve many important purposes: They introduce new ideas to their affiliated agencies and can act as a bridge between government and nongovernmental sectors—even helping to break an impasse among disputing agencies and bring more stakeholders to the table. According to Fengshi Wu, the unique place of GONGOs between state and society can encourage greater public participation and ensure environmental equity.

Fengshi Wu noted while many GONGOs may seem very autonomous they are not true NGOs for they do maintain unusually close relations with the government. Nonetheless, they are in some respects separate from the traditional scope of government agencies in that they have some financial, legal, and organizational autonomy. Not all GONGO staff members are government employees and the government only partially covers salary and operational costs. Like NGOs, however, GONGOs perform purely non-regulatory functions. They cannot, for instance, order local agencies to implement certain projects.

GONGO development began in the mid-1980s, not coincidentally soon after the central government began to acknowledge the breadth and depth of China's environmental problems. The government, having realized its lack of capacity to deal with the problems, began to form these quasi-governmental agencies in part to take advantage of the growing environmentalism throughout the country. Fengshi Wu profiled several environmental GONGOs that have emerged in the last two decades. Organizations are usually created by SEPA, but often founded in cooperation with foreign governments and multilateral organizations like UNDP, GEF, and UNEP. These "green" GONGOs address issues as diverse as facilitating public environmental education, advising the government on energy efficiency policies, supporting renewable energy businesses, and empowering citizen environment activists.Because many GONGOs are still quite young, evidence of their impact in China is largely anecdotal. Nevertheless, Fengshi Wu insisted they are performing a very important role in promoting environmental protection in China. Perhaps because they must compete for their funding, GONGOs are not passive political players; rather they offer creative policy alternatives, advocate new principles, and present innovative ideas to solving China's environmental problem. Most importantly, they fulfill a very important role in providing information to the public, giving them information to better protect themselves. In this, they offer many opportunities to promote participatory equity.

Voice from the Grassroots

When Wen Bo began his career in environmental activism thirteen years ago, he was detained by police for simply posting a sign on a college campus in celebration of Earth Day. The political space for environmental activism has grown considerably since those days. Despite onerous registration requirements, green NGOs have cropped up throughout the country, a symptom of China's growing environmental problems and the great number of citizens willing to engage in the taxing work to resolve them. Even some environmental GONGOs have undertaken somewhat activist roles. There are, however, small informal green groups that are unconstrained by government regulation. Their unique "under the radar" existence enables small informal groups to play a significant role in assuring participatory equity for even more Chinese citizens than perhaps the NGO and GONGO groups combined.

Surprisingly, nature clubs are among the more influential informal groups. Though they might begin as a rather benign crowd of birdwatchers, as environmental degradation negatively impacts their hobby, nature groups around China have mobilized and engaged in work akin to larger, better organized Chinese NGOs. Wen Bo presented a recent example of a Shanghai nature club that, in 2002, began to protest the planned development of a local wetland. The club informed the local news media of the imminent destruction of the wetland that was the habitat for many local and migrating birds. Club members constructed a Web site to inform the public about the development and instances of corruption involved in the project. In the end, influential government officials were pressured into canceling the development altogether thus saving the wetland from destruction.

According to Wen Bo, the Internet plays a key role in the work of many informal environmental groups in China. Web sites help groups circumvent the sometimes restrictive registration laws to which NGOs are beholden. The unregistered status of "Netizen" groups precludes the possibility of formally recruiting members. But by recruiting members through the Web site as simply "Web users" and asking for "donations," the groups are able to, in effect, act just like a registered NGO. Notably, registered NGOs are prohibited from forming branch offices in other cities, however Netizen groups can spread their message throughout the country.

Greener Beijing is the largest of these Internet groups, which has established itself as one of the most effective pressure groups in China. Notably, in 2001 television advertisements touting the medicinal benefits of consuming a rare species of turtle began to crop up on Hainan Island television stations. Though well over 1,000 miles from this Internet group's Beijing home, through its Web site Greener Beijing was able to spread the message to Web users throughout China to inform each other about the advertisements on Hainan. In chat rooms and Internet bulletin boards, word spread quickly and many members within the Greener Beijing network began to call the Hainan television station and government officials. Due to their efforts, the ads were pulled off the air.

These small informal groups can be very dynamic, using creative means to register, recruit members, raise funds, and perform work. By becoming a vehicle for individuals to air grievances and pressure local governments, informal organizations are providing a great number of Chinese citizens the opportunity to get involved and participate in the environmental policy process. These small groups do face the challenge of operating on a small budget and relying solely on volunteers. Lacking the legal status of formal groups, securing financial support is also quite difficult. Ideally, many of these groups would prefer to be registered, but the current legal framework for registration is an impediment.

Big But Vulnerable—Elephant Protection and Poverty Alleviation Conundrum

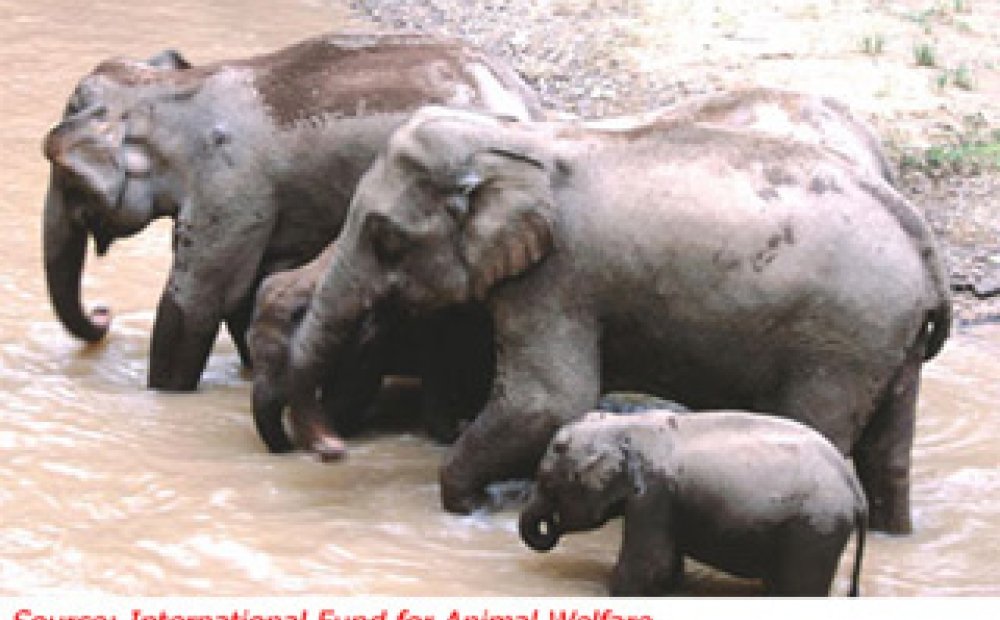

Aster Zhang's profile of the clash of growing human populations invading natural habitat and threatening animal species underlined how environmental inequities may very well be a bigger issue in China's rural areas than the cities. The Asian elephant is just one such species under threat of extinction by population pressures in southwest China. The original forest habitat for Asian elephants that once helped the species thrive, has been developed for agriculture or destroyed by the logging industry. Over the past fifty years, Asian elephant numbers have dwindled considerably as the habitat has been destroyed and its population fragmented. Some elephants have begun to, in effect, fight this encroachment.

Zhang took part in a study in Yunnan province that found elephant damage to crops and homes accounts for almost 20 to 50 percent of the average farmer's 150 USD annual income; additionally, over five years twelve people in the research area lost their lives to elephants. Retaliation against elephants have in turn led to two elephant deaths in one year; though illegal, growing demand in the ivory market caused the death of 16 elephant in 1996.

The economic and environmental implications of the elephant-human conflict are examples of overlapping regional inequities—unlike their east coast counterparts, poor farmers in southwest China lack access to markets and must often rely on subsistence farming. In addition to lacking economic opportunities these areas receive much less government investment for development and resource protection. Notably, an international NGO—International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW)—joined with Chinese researchers and local governments and communities to create a project aimed at correcting these economic and environmental inequities and assure that elephants and humans can live and prosper together, without conflict. Launched in 1999, this IFAW-led project first conducted surveys of the local economy, society and natural habitat to identify the key problems. This survey information enabled IFAW to design a three-pronged problem-solving approach: (1) provide scientific data for a "conservation corridor" design, (2) execute a community development project to support alternative eco-friendly economic activities, and (3) set up environmental education activities to help the communities understand the needs of the elephants.

Simao was the site of one particularly successful community development initiative in which IFAW created a micro-credit project involving groups of several families that organized themselves to secure $100 to $200 seed money. The money was used for development projects that provided steady income for the families, but did not threaten forest resources. Zhang reported that 98 percent of the village's families participated in the project. Two years into the project, $40,000 was distributed to 370 households; the rate of return was nearly 100 percent and the projects sparked a marked increase in the standard of living in the area. The economic success for the humans brought a windfall for the elephants in that a significant amount of land was been returned to its natural state. Zhang noted that rural people have the right for development, just as their urban counterparts. But the rural development needs to be kept in check, for if the local ecosystem is destroyed humans and animals alike will have no future.

Energizing Economies and Fueling Inequities

Regional economic inequity in China has become more extreme over the past twenty years—coastal regions boast a relatively high GDP, while revenues are markedly lower throughout the rest of the country. Similarly, there are great regional disparities in energy use with the east using much more than inland China. Andreas Oberheitman contended that because of differences in energy use, China also has great regional disparities in SO2 emissions. The highest emissions levels are found in well-developed areas, on the eastern and southern coasts of the country, as well as in some less developed poorer inland provinces like Heilongjiang, Inner Mongolia, and Anhui. These high pollution emission areas account for nearly two-thirds of China's total 240 million tons of SO2 annually.

Pollution from energy is not, however, limited to poor air quality in these areas. Oberheitman asserted that though the highest demand for energy comes from coastal areas, the primary energy source, coal, is located in underdeveloped inland areas. These high-energy use provinces must import fossil energy from across the country, putting a tremendous demand on China's weak transport infrastructure. Moving coal is a costly venture. In 2001, the total rail freight traffic of fossil fuels was nearly 700 billion tons; the average distance to transport this energy source was 555 kilometers, costing roughly 20 billion USD. Such long-distance coal transportation has led to an unintended, perhaps ironic, consequence—great amounts of energy are exhausted for the sheer purpose of transporting energy. Oberheitman explained that in some cases when all energy use is taken into account, it takes as much energy to move the coal as the energy it later produces. In addition to the costs of transportation, the environmental costs of mining the coal are borne more heavily by the exporting provinces. The costs of cleaning up these environmental externalities are not built into the sale of coal, for prices are kept low by government subsidies.

Oberheitman suggested several strategies that might lower China's dependence upon high sulfur coal for energy. The government has already made an effort through the "Go West" program to encourage better income distribution across China, which Oberheitman views as an opportunity to increase investment in energy-efficient technologies or renewable energy sources such as nuclear, wind, or solar energy. To deal with the high-energy use needed to transport energy, the government should reduce freight traffic and improve the overall transportation infrastructure.

But even if the government was interested in these strategies to lessen energy inequalities, the high costs may prove too prohibitive. Arguably only the economically developed coastal regions will be able to implement new low polluting energy options, while the poor inland areas will likely continue to rely on highly polluting fossil fuels and coal as they develop. New energy strategies for these regions must be more practical. Oberheitman suggested that washed coal could lessen the negative impact on the environment and bring down energy costs. This process minimizes the fuel's weight, making energy use and cost of transportation lower. Moreover, washing the coal significantly reduces sulfur levels, making it a less polluting energy source. While coal washing lessens the air pollution problems, it requires large amounts of water, a commodity that is in short supply in many regions of the country. The regional disparities surrounding energy production, transportation, and use are admittedly challenging, but must be dealt with in the long run if the Chinese government wishes to fully succeed in promoting economic and environmental equity in the China

The Tamaki Environmental Project continues beyond this series of meetings. The participants in these meetings have been joined by other environmental experts to contribute chapters to a comprehensive volume that will address many different issues relating to environmental equity in China. The Tamaki Foundation has generously funded these meetings at the Wilson Center, a summer conference in Germany, and the upcoming book. For more information on this initiative contact Jennifer Turneror Miranda Schreurs at the University of Maryland.

Drafted by Timothy Hildebrandt and Jennifer L. Turner.

Speakers

Hosted By

China Environment Forum

China’s global footprint isn’t just an economic one, it’s an environmental one. From BRI investments in Africa and Asia to its growing presence in Latin America, understanding China’s motivations, who stands to gain - and who stands to lose - is critical to informing smart US foreign policy. Read more

Environmental Change and Security Program

The Environmental Change and Security Program (ECSP) explores the connections between environmental change, health, and population dynamics and their links to conflict, human insecurity, and foreign policy. Read more