The Trump Administration Embraces the Saudi-Led War in Yemen

President Trump enthusiastically promised Saudi Arabia wholehearted support for its campaign to roll back Iranian influence in the Arab world during his visit to Riyadh May 20-21, offering a $110 billion arms sale package to prove it. And it will shortly begin re-supplying the Royal Saudi Air Force with $500 million worth of smart bombs and other munitions in preparation for what is shaping up to be a make-or-break battle in the stalemated Yemeni civil war.

In question is the strategic Red Sea port of Hodeida now in the hands of Iran’s Yemeni allies. The outcome may well decide whether the already war-fragmented nation is re-divided into North and South Yemen as it was for 23 years until 1990. It may also determine whether Iran ultimately establishes a naval base in Hodeida from which to threaten U.S. warships and commercial ships passing through the nearby Bab el-Mandeb Strait. Already, Iran’s new-found allies in Yemen, Houthi rebels and their allies, have attacked both military and civilian ships in or near the strait with missiles, rockets, and a drone boat.

The risk is high that the Trump administration will now be blamed for making the world’s worst humanitarian crisis even worse. Hodeida is the main gateway for delivering desperately needed relief supplies into the mountainous interior where millions of Yemenis are suffering from famine as a result of the war that has laid waste to much of the country’s infrastructure and health facilities and taken 10,000 lives. The battle over Hodeida is certain to close down its port for months.

UN reports say that 17 million Yemenis, about half the population, are “food insecure,” and 6.8 million are “one step away from famine.” More recently a fast-spreading cholera outbreak has affected 124,000 people and caused nearly 1,000 to die already. These reports blame both sides for the humanitarian catastrophe, but place the onus on bombings of civilian targets by the Saudi-led coalition.

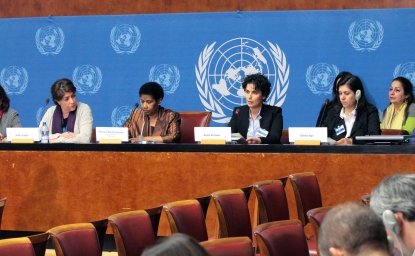

International humanitarian groups, the UN’s special peace envoy for Yemen, and a sizeable faction in Congress have all been pressing the Trump administration to stop the attack on Hodeida. A Senate resolution on June 13 to block the latest $500 million munitions sale came within four votes of passage. Even if blocked by Congress, the Trump administration was reportedly ready to send some of the 17,000 “smart” laser-guided bombs and unguided “dumb” ones already approved by Congress last year, but blocked by the former Obama administration because of high civilian casualties.

Even Trump’s military advisers have been counseling the Saudis to strive for a political solution rather than a military victory, just as former President Obama did previously to great Saudi dissatisfaction. “Our goal is to push this conflict into UN-brokered negotiations to make sure it is ended as soon as possible,” said Defense Secretary Jim Mattis during a visit to Riyadh in mid-April. But the UN special peace envoy, Ismail Ould Cheikh Ahmed, reported to the Security Council on May 30 that he had made no progress in cajoling the warring parties toward a political compromise. The Houthis, who shot at his car the last time he showed up in Sanaa, have said they will no longer deal with Cheikh Ahmed, alleging he is biased against them.

The ambiguous U.S. military attitude stems partly from serious doubts about the military capabilities of the Saudi-led coalition of nine Arab countries backing Yemen’s internationally recognized government of President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi. It is based in the southern port city of Aden. After more than two years of fighting, the Yemeni capital, Sanaa, is still occupied by the Houthis and their powerful military ally, former President Ali Saleh, who has maintained the loyalty of key army units.

The Saudi coalition depends heavily on Special Forces from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Yemeni tribesmen supporting Hadi’s government for ground fighting. But the U.S. military assessment is that they are not ready militarily to launch the most complicated and consequential battle of the war.

Meanwhile, it is far from clear Trump regards Yemen of special importance. In his Riyadh speech to leaders of 50-plus Muslim nations, he called for “responsible nations” to work together to end the humanitarian crisis in Syria but said nothing about the even worse one unfolding in Yemen.

Trump seemed to go out of his way to avoid mentioning Yemen’s strategic location on the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, stating instead that the “entire region is at the center of the key shipping lanes of the Suez Canal, the Red Sea and Straits of Hormuz.” In fact, most maritime trade between Asia and Europe, including 4.7 million barrels of oil a day, pass through the 16-mile-wide Bab el-Mandeb Strait that commands the southern opening into the Red Sea that leads northward to the Suez Canal.

Pentagon officials, however, are well aware of the Houthi threat after a series of missile, rocket, and boat attacks from the Yemeni coast last year on both commercial and military ships. In October, two U.S. warships, the USS Mason and USS Ponce, were subjected to missile fire but suffered no hits. In response, U.S. Navy ships launched a cruise missile that took out radar sites located in Houthi-controlled territory along the Yemeni coast.

If the Saudi-coalition succeeds in driving the Houthis out of Hodeida, there is some hope of keeping Yemen united. But if no attack is launched or it fails, the likelihood of seeing Yemen stay together seems slim. Already the country is drifting toward a reiteration of the old North and South Yemen. A southern secessionist movement has been revived and is contesting the authority of the Saudi-backed Hadi government even in Aden. UAE forces, increasingly sympathetic to the movement, took control of the Aden airport from pro-Hadi forces at the end of May.

The Saudis remain determined to take back Hodeida, believing this will finally give them the necessary military leverage to force Houthi leaders to accept the demands of U.N. Resolution 2216 adopted in April 2015. These include the Houthis-Saleh forces withdrawing from the capital, handing over their heavy weapons (presumably to the internationally recognized government), and accepting a political compromise worked out before the Houthis seized Sanaa in September 2014.

The Saudis’ main objectives are to keep Iran from establishing a permanent foothold in Yemen, cut the Houthis’ military ties to Tehran, and prevent them from establishing a separate militia modeled on the Iranian-created Hezbollah in Lebanon.

The Saudi plan to take back Hodeida counts on a combination of Yemeni tribesmen and Emirati Special Forces, which have been training for months at a UAE naval base in Assab, Eritrea for a simultaneous sea, land, and air assault. But U.S. military advisers who have reviewed their performance warned in April that more training was needed before launching the complex operation. This is one reason it has been postponed five times, according to Saudi sources, though international pressure to forgo the assault and a shortage of U.S.-provided munitions seem just as significant.

The same combination of UAE-Yemeni forces successfully drove al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula from the port of Mukalla in eastern Yemen in April 2016. But in that case, al-Qaeda mostly withdrew its forces without putting up a fight. By contrast, the battle for Hodeida is expected to be more like the prolonged struggle by U.S.-backed Iraqi forces to oust Islamic State fighters from Mosul. Hodeida is the last Red Sea port in Houthi hands, and they have had ample time to prepare their defenses since the attack has been advertised as “imminent” for the past three months.

Even if the Saudi-led coalition goes ahead with its assault on Hodeida, the prospects for a pyrrhic victory remain high. The Houthis could still cut the roads leading out of the port city and could easily paralyze ship traffic by firing their Russian- and Iranian-provided missiles from the nearby mountains they still control. Relief supplies still would not get delivered. In any case, the outcome holds enormous consequences for both Yemen’s future and the first test of the new Trump administration-Saudi alliance against Iran.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not reflect those of the Wilson Center.

Author

Former Washington Post Middle East Correspondent

Middle East Program

The Wilson Center’s Middle East Program serves as a crucial resource for the policymaking community and beyond, providing analyses and research that helps inform US foreign policymaking, stimulates public debate, and expands knowledge about issues in the wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Designating Houthi Militia as FTO: A Matter of US Security and Global Stability

In Yemen, Russia Drops Political Diplomacy to Support Houthi Militants