This is an unedited transcript

Hi, I'm John Milewski. Welcome to Wilson Center. Now a production of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. My guest today is Robin Wright. Robin is a Wilson Center distinguished fellow and one of the country's foremost authorities on the Middle East.

She's an author of multiple books and an editor, and she also is a longtime contributing writer for The New Yorker. Robin was a diplomatic correspondent for The Washington Post and has reported from, get this, more than 140 countries. She's joining us to talk about the war in Gaza and the implications for the region. Robin, welcome. Always a pleasure to see you and to speak with you.

Always a pleasure to be with you, John. So we had some breaking news today about Hamas counterproposal to a cease fire proposal. And almost instantly, it's a nonstarter for Israel because it requires a complete withdrawal from Gaza. And Israel right now is not even willing to talk about that. So is this anything that is worth talking about or is this really back to the drawing board time?

The challenge for Israel is to find a formula that will diminish the presence or the political influence of Hamas, provide security for Israel and get back the 100 or 130 so hostages that have been held since October seven. The challenge for Hamas is getting an end to the war, ensuring that it survives as an ideal, a political entity or as a governing party, and to have some leverage over Israel and in a step that will ultimately lead to a Palestinian state.

Now, that's asking an awful lot. And I think there are still some stages to go through. At the end of the day, Gaza has been so destroyed more than 85% of the population have now been displaced. More than half the buildings in Gaza have been either damaged or destroyed. And the vast majority are dependent on some form of humanitarian aid.

The economy has collapsed. And so this is there's still a long way to go. But the one bit of leverage that Hamas has over Israel, over human lives, the people it holds. And so it's going to exact a high price. And I suspect that Hamas is going to demand the release of hundreds of Palestinian prisoners, as well as part of any eventual deal.

What when? Try to imagine an endgame, which at this stage of the conflict, it's hard to do. So the two state solution keeps coming up. But Benjamin Netanyahu has made clear that he's not interested. Is there any hope for some solution that doesn't involve a two state scenario? Well, I've covered peace talks since 1978, and I've covered every war since 1973 and in every previous peace process, there have been two parties, one that wanted a deal and the other that was pressured into talking and was willing to consider a deal.

Today, we are at a point that the two adversaries, Israel and Hamas, both have existential goals to destroy each other. And so that makes the idea of a two state solution or a political process that ends in peace or in dignity for everyone ever more difficult. I've never seen a harder a tougher moment in U.S. diplomacy in the Middle East and in shaping a future for the Middle East by the people in the region.

And Benjamin Netanyahu, the prime minister, has rejected the two state solution. Hamas has in the past engaged in what's known as a hudna, kind of a temporary cease fire, coexistence, no deal, no y peace process. But at least they coexisted if not formally. And I think that's probably the best we're going to get in the short term. The United States has been insistent that the two state solution is the ultimate goal, but it's very hard to see how we get there, because today there are not only two parties, there are three.

Remember, the Palestinians are divided. You have a Palestinian Authority in the West Bank and Hamas in power in Gaza since 2007, since the two Palestinian factions split. And how to get the Palestinian to speak with one voice is going to be a huge step because various U.S. administrations have tried. Are others of the Egyptians as well have tried to get the Palestinians to speak with one voice and they haven't been in, you know, 15, 16 years now.

So, Robin, how much does Benjamin Netanyahu's Netanyahu's political future factor into this equation? You know, you look at the public opinion polls in Israel and it seems as if the electorate would like to replace him now, But certainly that's not going to happen in the short term. Is there some scenario where a different Israeli government might consider options that Netanyahu won't even discuss?

Well, Prime Minister Netanyahu is has been in political trouble long before October 7th. Remember, there were mass protests against his proposal to agitate for judicial reforms that would have weakened the power of the court in dealing with issues of the state. You know, who was the ultimate power or or adjudicator? And and there are many in Israel who blame Netanyahu for not having the kind of response or the security in place that would have prevented what were terrible atrocities.

But I think we have to remember one thing, that even if Benjamin Netanyahu is not around that public sentiment is still shaped largely by what happened on October 7th. And I talked to a Palestinian pollster a few weeks ago, and she pointed out that with every war, the Israeli population turns further right. And at the last election, somewhere around 48, 49% of the population voted for right wing or far right wing parties.

She estimated that in the aftermath of what's played out now, that anywhere from from 60 to 64% of the population could vote for a right or right far right wing party. And so that could mean that many of the things that are on Bibi Netanyahu's agenda are still supported, even if Netanyahu is no longer around. This is this has been the most traumatic thing for the Jewish population, not just in Israel, but around the world since the Holocaust during World War Two.

And security is foremost in their minds. And while Netanyahu has had an incredibly long career, at the very end of the day, many feel that that he failed them. And so I think, you know, his prospects are now in question. But I think the sentiment of the Israeli population is not. You mentioned earlier that you've never seen such an intractable situation or a sticky wicket that the current set of circumstances, which is saying a lot because you've seen a lot.

So what has that done to the view of the United States in the region? Is there irreparable harm here for the very staunch loyalty that President Biden and the U.S. has shown toward Israel? Has that diminished its standing with other countries in the region? Well, let me just preface this by saying the reason I think it's so dire right now is because before October 7th, there were ten different conflicts playing out across the region, different adversaries, different issues, different flashpoints, different arenas.

What's happened since October 7th is that diverse conflicts are beginning to merge into one larger war. And that's why I think that the momentum of all of these things, whether it's the Houthis firing on ships in the Red Sea in the Gulf of Aden, and this is a waterway through which a third of the world's ships pass for commerce and for naval purposes.

You have the Americans in Iraq and Syria who are there to fight and contain the remnants, vices totally unrelated to the Arab-Israeli conflict. And then you have Israel's other flashpoints, the northern border with Hezbollah and so forth. So I think this is why it's so complicated. Now, when it comes to the United States. It traditionally has been the only power capable of brokering some movement.

Not always peace. There have been so many, many, many failed peace processes that the United States has led, gotten close and only to see them fall apart. If the United States doesn't make headway, I think it does diminish the standing of the United States, no matter who is in the presidency or in the White House. This is a moment that whether it's a Republican or Democrat, Democrat or Republican, that the world is looking for leadership and to use its influence as leverage to get the parties to some kind of compromise.

And I think one of the things we've witnessed in the last few weeks is the kind of rift, the very public rift between Israel and the United States. Secretary Blinken is in Israel as we speak today. He has been very consistent in what he said and President Biden and any spokesperson about the desire to contain this, a Nazi has spread to the broader region.

You and others have made the case that really in many ways, the spread is already there. The question is one of escalation, not really of whether there is a broader conflict. What are your concerns there? What are your thoughts on how could this become even a more a hotter war across the region with more nations involved? Or is there is it possible to keep a lid on this?

Well, I think we've probably crossed the threshold of escalation. There's been so much hype and speculation. Is it going to escalate? Is it going to escalate? Yeah, we've already gotten we crossed that point. But the question is, how can we contain the momentum? You know, this there is there's the way that these conflicts have been integrated and the Houthies saying they're not going to stop attacking ships in the Persian Gulf until the Gaza war is ended.

And, you know, U.S. troops were trying to carry out a mission against ISIS or coming under attack from militias and the axis of evil, which is a wide network of Iranian backed militias in the region that are allied with Hamas and Hezbollah, but have their own agendas domestically. And they want the Americans out unrelated to Gaza. So this is again, it's not just about whether the United States can get a deal between Israel and Hamas.

That is short, short term, you know, cease fire, exchange of hostages that then becomes in some way permanent and allows a political process to take place. I think it's you know, the steps are obvious. They have been for years in terms of how do you get to a two state solution. But there's always some issue that comes up that blocks things and then it deteriorates.

And we've gotten to a point that is going to be harder than ever. But then, even if in the best of all possible worlds, you get a deal, there's a not just a road map to we've had road maps before to a two state solution, but there is the beginnings of it moving beyond the Oslo Accords, making something that is tangible.

Then you have to deal with all these other flashpoints. And we talk about, you know, when did this all began? Was it the American invasion of Iraq in 2003? I think it goes back 40 years of the tensions emanate in many ways the kind of core issue where the flashpoint the original flashpoint was the Iranian revolution in 1979, which was designed as much as to get the US out of the region as to and the monarchy.

And for that and and Iran has has unfortunately been very successful at creating a network of militias willing to take on major powers, whether it's Israel, the United States or U.S. allies in the region. And so we have you know, we have an immediate problem and then we have a long term problem that dates back decades. And I don't think we actually get to a place where there's equilibrium in the region, a stable stability, even if there are still rivalries, political rivalries, there will always be somewhere where they're not fighting each other.

I think that's a much bigger picture and it's going to take much more than a few weeks or a few months. On the question of Iran and the role of Iran in the region and potentially behind the scenes in a conflict like this, you know, your work on Iran has set the standard really. And you've been watching this country for a long, long time.

How would you tell people to think about Iran in the current conflict? Of course, when there were U.S. troops killed a little over a week ago, right away, there were a lot of finger pointing at Iran. How should we think about Iran's role in what's happening today in Gaza? As I first went to Iran in 1973. So I'm now a half century into this country.

I've seen it both under the monarchy and the theocracy. Look, it's very easy to slap on labels like Iranian backed militias. And it is true that Iran has created or fostered armed, trained, financially aided, politically supported militias in Lebanon, Hezbollah, the Palestinian territories, both Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad in Iraq, an array of other militias that come under the rubric of the Popular Mobilization Forces and, of course, the Houthis in Yemen.

Now they all share a strategic goal, one to challenge Israel and to to get the United States out of the Middle East. But many of these groups have their own local agendas. Iran was able to to create or assist these people by going into countries where there was a very large, disgruntled, unhappy, unrepresented polity and Iran helped create militias.

But over the last four decades. All of these militias have integrated politically into each of these countries in ways that have made them very influential political parties that cannot simply be pushed aside with, you know, airstrikes and artillery. And so the real challenge is kind of understanding that it's the network dealing with each of these militias in context of their state.

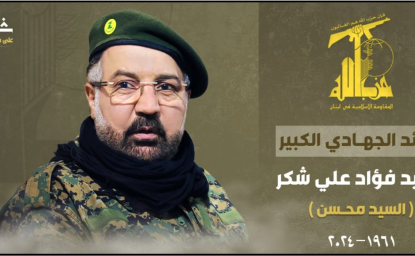

And one of the reasons Hizbollah has not joined in beyond I mean, Israel has fired more than 700 rockets or missiles into northern Israel, but it has been very restrained, given what its arsenal. It has 150,000 rockets or missiles aimed at Israel could do far more. Opening up a whole new front that is far larger than Hamas could.

I think it's been restrained in part because Lebanon is a failing state now. Hezbollah is a big political player, has cabinet positions, several members of parliament, and it knows that a war would be could be the end of Lebanon itself, because it's already a failing state. And so these groups have to deal with their own constituencies now. And the challenge is thinking big.

Imagine imaginatively, boldly, how do we deal with the kind of political reality realities? How do we deal with the populations that have gravitated to these extremist groups? And that's just a huge challenge. Undoing a problem with 40 years could take another 40 years. This is you know, this is something we've kind of let happen. And again, not not that we should necessarily use military force, but we need to understand the political realities on the ground.

We haven't been very good at that. A final thought, Robin and I and forgive me, I'm not asking you to speculate, but I'm just curious of how your your thinking about this. You know, probably the most accurate conclusion to a discussion like we've just had would be to be continued. Right. Because we don't know what's going to happen next.

But how are you thinking about this in terms of best case, worst case scenario for when this hot conflict in Gaza might be resolved in some manner? Are we talking about months or years? Well, you know, the immediate crisis is, you know, if we get a cease fire, one can only hope that it it lasts and it becomes kind of a fait accompli, a cease fire, that no one starts firing guns again.

The danger is the language is such by both sides that it's hard to ensure that it will a ceasefire will can be sustained. The some Israeli leaders have used words like annihilate Hamas. And I think that's virtually impossible because Hamas is an idea. It also represents or gives something for people to believe in, in a region where there is a vacuum of ideologies or isms that give anybody hope or feel like they're being represented by a senior European official who said to me, who's based in the region, spent his life in the region, who said to me recently that even his tennis playing Western educated colleagues and friends in places like Jordan admire Hamas not

for its ideology, didn't approve of its tactics, but admired or envy. The fact that it had stood up to the US and Israel. And this is the danger that there are these lurking problems in the region. The, you know, what is the future? Is it all of these autocrats and dictators who have consumed all the political space, sucked it up in ways that gives no room for people to participate in that kind of environment?

The you know, we could see a rebirth of the kind of political Islam that ultimately created the Islamic State. We'd all hope that that kind of movement of extremism had atrophied or died with the end of the Islamic State caliphate in 2019. And the danger is we see its rebirth in yet another form, in part because there are no alternatives.

So again, this is where I go back to the big picture. Yes, we're all consumed with is there a cease fire today? Is there a return of 130? So, you know, traumatized Israelis? The bigger picture is to find a way to stabilize the region, is going to involve a lot of big thinking, a lot of bold action and dealing with things that we've kind of tried to avoid for a long time.

And it's not something that the US can solve by itself. This is the region has to work for its own future to the optimism that a lot of us held in the early days of the Arab Spring seems a millennium away now, doesn't it? Well, at the end of the day, I believe that, you know, political science has been right about the three waves of democracy.

It takes that we saw that in Eastern Europe, whether it was in Hungary, you know, and in Czechoslovakia in the fifties, sixties. You know, there the Prague Spring didn't work so well, but it came back and it became a democratic state. I think this was the first wave we saw. And you it captured the spirit and the desires of millions of people.

The problem was they didn't have the networks, the political sophistication, the resources or the kind of alternative solid, tangible political alternatives or leaders even to take the place of the dictators. So, again, they need to mobilize, grow and figure out ways to create alternatives. But that takes time. It takes decades. And that's why I think this is a long term problem that we can no longer avoid.

You know, straight lines, fits and starts. Robin Wright, always a pleasure. And I always feel smarter after speaking with you. Thanks for joining us today. Thank you. Our guest has been Robin Wright. We hope you enjoyed this edition of Wilson Center now, and you'll join us again soon. Until then, for all of us at the center on John Molesky, thank you for your time and interest.