El Voto Femenino

El Voto Femenino

This year, the United States commemorates a century since the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, when the United States became the first nation in the Americas to approve women’s suffrage.

In 1929, Ecuador became the first nation in Latin America to grant women the right to vote. Since then, almost all democratic Latin American countries have passed legislation to extend voting rights to women and implemented quotas to increase female representation in their national legislatures. The region has seen 11 female presidents, beginning with the first elected female president, Nicaragua’s Violeta Barrios de Chamorro in 1990. Still, a century since the milestone voting rights decision in the United States, gender equality in Latin America is far from achieved.

Despite most countries requiring quotas for representation, women in Latin America hold less than a third of cabinet posts, a third of legislative seats, a third of judicial appointments to the highest court and less than a fifth of mayoral positions.

This persistent lack of female representation and influence has weakened gender-oriented policymaking, including on issues such as poverty, reproductive rights and gender-based violence that have a disproportionate effect on women.

The Foundational Years

The U.S. women’s suffrage movement and the passage of the nineteenth amendment had a transnational effect on feminist movements. But throughout Latin America, feminist movements also had their own priorities and strategies, and their progress was oftentimes tied to broader social transformations that helped advance feminist movements.

This was clear in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920). During the conflict, female combatants known as adelitas fought alongside their male counterparts, changing the image of women. Female participation contributed significantly to the revolution’s success, which lead to the gradual expansion of labor and education rights, and catalyzed the country’s first feminist congresses.

The First International Feminine Congress, held in Buenos Aires in 1910, gave Latin America some of its most prominent suffragist voices, such as Paulina Luisi, Amanda Labarca and Sara Justo. They laid the foundation for subsequent feminist movements throughout the continent. In Uruguay, the 1917 constitution afforded women equal civil and political rights, including the right to vote, but women did not cast ballots in a national election until 1938. In 1929, Ecuador adopted a new constitution that expanded suffrage to women, but it included only those who were literate. Women who lacked formal education, and the majority of the indigenous population, did not earn the right to vote until 1978.

The Vote

The 1930s saw important advancements in women’s rights in Latin America. In 1933, during the 7th Pan-American conference in Montevideo, participants recommended nations adopt treaties on women’s political and civil rights. In 1938, the Inter-American Commission of Women adopted the Lima Declaration in Favor of Women’s Rights, which promoted women’s right to “political treatment on the basis of equality with men and to the enjoyment of equality as to civil status.”

Gradually, countries in the region passed laws advancing gender equality. In 1961, for example, Paraguay became the last country in Latin America to enact universal suffrage, though challenges remained, as literacy requirements continued to deprive indigenous and Afro-descendant women of their voting rights.

Dictatorial Years

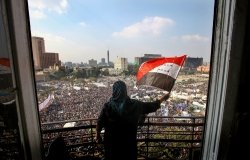

After a period of impressive advancements in expanding women’s rights, political instability and authoritarianism jeopardized these gains. By the 1970s, most Latin American countries were governed by dictatorships, restricting all citizens’ political and civil liberties. During this time, women organized for political change through civil society organizations, which condemned extrajudicial killings and kidnappings at the hands of the state.

Democracy made a comeback in the 1980s, marking a new phase for women’s movements in Latin America. Key to the post-authoritarian agenda was addressing the lack of women’s representation in elected office. In 1991, Argentina became the first country to mandate that 30 percent of its legislature be female. Since then, practically all Latin American countries have passed similar legislation, though some have been more successful than others in enforcing gender-based quotas.

Meanwhile, female heads of state in Latin America are not uncommon nor a particularly modern phenomenon. The first woman to lead a country in the region was Argentina’s Isabel Martínez de Perón, who was her husband’s vice president and succeeded him following his death in 1974. Sixteen years later, Nicaragua elected the first female president in Latin America. She was followed by Guyana’s Janet Jagan in 1997, Panama’s Mireya Elisa Moscoso in 1999, Chile’s Michelle Bachelet in 2006, Argentina’s Cristina Fernández de Kircher in 2007, Costa Rica’s Laura Chinchilla in 2010 and Brazil’s Dilma Rousseff in 2011.

Road Ahead

While women have broken the glass ceiling in many nations in the region, politics remains a male-dominated sphere, and men remain the gatekeepers. Most of the region’s female presidents were elected after serving as first lady, or on the coattails of male predecessors, though there are exceptions, such as Ms. Barrios de Chamorro, Ms. Moscoso, Ms. Bachelet and Ms. Chinchilla.

Worryingly, however, female politicians are still subject to harsher scrutiny than their male counterparts. A study of Colombian female representatives, for example, found that a quarter felt silenced or unsupported by members of their own party.

Filling the Gaps

Women elected to public office in Latin America are whiter and wealthier than the general population. That said, indigenous, Afro-descendent and LGBTQ politicians have made notable inroads. In 2010, Eufrosina Cruz became the first female and indigenous chair of the state congress in Oaxaca, Mexico and is considered one of her country’s most powerful women. In 2018, Espy Barr of Costa Rica became the first Afro-descendent woman to become vice president in Latin America. In 2019, Claudia López was elected mayor of Bogotá, the first openly gay woman to hold a mayoral position in a major city. That same year, Joenia Wapichana was elected as the first indigenous woman to serve in Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies.

Though the region has made strides in addressing its historic erasure of women in public life, there are consequences to its halting progress in recent decades. Racial, ethnic and gender minorities continue to be underrepresented, and notable gaps remain in policies to benefit all women. Indeed, as a result of the region’s unfinished business in assuring gender equality, many countries in Latin America still face staggering rates of gender-based violence – most of which goes unprosecuted – and lag in reproductive rights. That said, new female voices in policy circles are drawing attention and advancing legislation to address the region’s gender equality hurdles, giving new hope to Latin American women.

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more