Under the North American Free Trade Agreement, NAFTA, trade between the United States, Mexico and Canada greatly increased, and agricultural trade strongly supported this growth. Between 1993 and 2013 the total value of agricultural trade between the United States, Mexico and Canada grew 233% (accounting for inflation) from USD16.7 billion to USD82 billion. The US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which replaced NAFTA, contains updated policies and procedures necessary to ensure continued agricultural sector growth in all three countries. If utilized properly, the USMCA can not only solve some key lingering trade issues but also expand on the successes achieved under NAFTA.

The benefits to agricultural producers, mainly in the U.S. and Canada, include increased free trade access to each other’s markets. Under USMCA, American farmers gain increased access to the Canadian dairy, poultry, and egg markets, in exchange for Canadian’s increased access to American dairy, sugar, peanuts and cotton markets. Mexico benefited from the fact that the USMCA locked in the important gains they already made to agriculture under NAFTA. All three countries should also benefit from the promotion of the “USMCA brand” which increases the competitiveness of the North America trading block.

The benefits expand beyond producers, however, to consumers who will continue to gain from access to cheaper and higher quality fruits and vegetables. According to the International Food Policy Research Institute, the increase in availability and decrease in price of fruit and vegetables under NAFTA contributed to the 11% increase in total per capita consumption of vegetables between 1997 and 2017 in the United States, likely helping improve the nutritional content in many American diets. Consumers will also benefit from the USMCA’s emphasis on science-based decision making on the use and expansion of biotechnology. The National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine agree that, in general, commercially available genetically modified (GMO) foods are safe to eat and have fewer negative environmental effects than non-GMO crops. The United States Department of Agriculture argues that biotechnology in agriculture could be used to nutritionally-enrich crops, lower the levels of naturally occurring toxicants, and conserve natural resources by creating crops that grow with less fuel, fertilizer and water. Additionally, agricultural biotechnology can be used to design crops that produce high yields which will help producers meet increasing food demands and despite harsher environmental conditions due to climate change.

Agricultural workers will benefit from the USMCA’s stronger labor protections. These rights will be upheld by the interagency labor committees which are in charge of tracking and investigating any claims made under the rapid response labor mechanism. USMCA empowers workers because, unlike NAFTA, anyone can submit a claim alleging that an individual establishment is failing to uphold workers’ rights to collective bargaining and freedom of association, and it is the responsibility of the offending party to prove the violation does not affect trade. Under NAFTA, the assumption was reversed and the party bringing a case had to prove that the violation affected trade. The prohibition on importing goods from forced labor should also support better working conditions.

Lastly, the agreement’s emphasis on environmental protections will benefit all workers, producers, and consumers by encouraging each country to take steps to reduce the negative impact trade can have on the environment. The agreement requires each country to adopt, maintain and implement 7 multilateral environmental agreements and requires a customs verification mechanism between the U.S. and Mexico to combat the illegal trade of flora, fauna, fish and forestry items. Furthermore, all countries are obligated to reduce marine litter, make air quality data publicly available, and promote sustainable forestry management. Progress towards these goals will be monitored by the Committee on Environment.

The USMCA, however, isn’t perfect, and some key issues remain to be solved during the agreement’s implementation. These include disputes over dairy between the US and Canada, and debates over biotechnology, corn, and seasonality between the US and Mexico. These long-running and complicated disagreements can be resolved if the tools and infrastructure outlined in the agreement are properly utilized. If successful, the USMCA will not only resolve these issues, but also provide a framework within which the agricultural sectors of the three countries can expand on the economic gains made under NAFTA for producers, consumers, and workers.

US-Canada: Dairy

Under the USMCA, U.S. dairy producers gained access to an additional 3.59% of the Canadian dairy market when Canada agreed to: (1) create a new tariff rate quota (TRQ) for US imported milk products in certain categories, and (2) eliminate class 6 and 7 pricing. Eliminating class 6 and 7 pricing removes production quotas from non-fat solids, such as skim milk components, milk protein concentrates, and skim/whole milk powder, which are created as a biproduct of butter production. Without this class 6 and 7 pricing, foreign and domestic producers can compete in these categories normally. The creation of a new TRQ for the United States increased US market access to export fluid milk, cheese, cream, yogurt and several other dairy goods to Canada.

This was perceived as a significant gain to American dairy producers. However, since the deal’s implementation many American dairy organizations argue they have been unable to realize such gains. In a May 14th, 2021 letter to United States Trade Representative (USTR) Ambassador Katherine Tai, 70 such groups wrote that Canada is in clear violation of the USMCA because they are reserving a portion of the TRQs for processors, which limits the number of TRQs for which American dairy producers can apply. On May 25th, 2021, Ambassador Tai formally requested a panel review about the issue, and in July, the USTR released its first written submission. In this submission, the USTR argues that Canada’s allocation of TRQs is not being allocated in a “fair (free from bias) and equitable (fair, just reasonable)” manner. By reserving some TRQ access for processors, before others can apply for TRQ quantities, Canada is not following obligations under USMCA to allocate quantities requested under TRQ applications “to the maximum extent possible”. Furthermore, USMCA requires consultation with parties before implementing new conditions, limits, or eligibility requirements for TRQ-allocation systems, which Canada failed to do.

As the first panel request put forward under the USMCA, this dairy dispute represents the first test of the agreement’s resolution mechanism. The panel is expected to release initial results in the fall of 2021, but ultimately the report only provides non-binding suggestions and both countries are free to do as they choose to resolve the issue. For example, the dispute could be resolved as soon as early-2022 if the panel agrees with the US, and Canada accepts the results and updates its TRQ allocation system. If the panel agrees with the US but Canada decides to object to the ruling, or the panel agrees with Canada, the US could move forward with a suspension of benefits by posting tariffs of equal amount to the damage done by the limited TRQ allocation. Either way, Canada’s decision will be influenced heavily by Canada’s domestic politics, in particular the results of the September 20th election, which will determine if Prime Minister Trudeau’s Liberal party will hold a majority or minority number of seats in the House of Commons. In the future, in-person annual meetings between members of the Committee on Agricultural Trade or the Consultative Committees on Agriculture should be encouraged as a way to facilitate dialogue and solution building.

US- Mexico: Biotechnology

The USMCA was the first free trade agreement to include provisions addressing agricultural products created with genome editing and other genetic engineering. The agreement emphasizes sharing information about new technology in order to cooperate on development and usage, writing that parties “confirm the importance of encouraging agricultural innovation and facilitating trade in products of agricultural biotechnology” and that parties will work towards “promoting transparency and cooperation, and exchanging information related to the trade in products of agricultural biotechnology”. The text also includes obligations to encourage the efficient processing of biotechnology approvals, writing that “if an authorization is subject to expirations, [parties must] take steps to help ensure that the review of the product is completed and a decision is made in a timely manner, and if possible, prior to expiration”.

Of the two main disputes between the US and Mexico about biotechnology, one has to do with this obligation for efficient processing of approvals, the other do with a Mexican ban on imports of genetically modified (GMO) corn by 2024. Mexico has not approved any biotechnology product applications since May 2018, and as of October 2020, 19 products are awaiting approval, of which 18 have exceeded the statutory timeline for response. During a July 7th 2021 meeting with Mexican and Canadian counterparts, Ambassador Tai addressed this issue and pushed for the timely processing of biotechnological product approvals in Mexico. Given the clear language about biotechnology cooperation and the approval process in the USMCA, this issue will likely result in a USMCA dispute case. The ban on the imports of GM corn, passed as presidential decree in December 2020, however, is unlikely to result in a dispute case in the near future. The scope and impact of this decree is difficult to portend given that it does not specify whether the ban includes animal feed (which represents a significant share of US exports of corn), in addition to corn for direct human consumption. Given this vagueness, and the extended timeline for adoptions, it’s unlikely to be brought to a dispute case in the immediate future, however, it represents a major potential for future trade disruption and should be monitored closely.

US- Mexico: Corn-based sweeteners

The ban on GM corn plays into a wider picture about US-Mexican disputes over corn and corn based-sweeteners. These disputes started as far back as 1998 when Mexico brought a case against the US to the World Trade Organization (WTO) claiming the US was dumping high fructose corn syrup on the Mexican market (a case it lost). In 2001, the US brought a case against Mexico’s 20% tax on beverages made with high fructose corn syrup to the WTO (a case the US won). More recently, in September 2019, the Mexican senate approved initiatives to protect native corn as part of cultural patrimony. These were eventually passed into law in April 2020. This law, the “Federal Law for the Promotion and Protection of Native Corn”, establishes areas where native corn will be grown with traditional methods, recognizes community seed banks as preservation centers, and creates a national council of native maize (which has not been created yet).

A March 2021 letter to Ambassador Tai that was signed by over 30 American organizations alleges that the GM corn ban and the federal law making corn cultural patrimony amount to a coordinated effort between the Mexican government and advertisers to disparage US corn sweeteners, assert that US corn sweeteners are subsidized and dumped on the Mexican market, and claim that corn sweeteners are different from cane sugar (and worse with regards to their impact on health). The letter sums up all these issues by writing that “food and agriculture trade relationship with Mexico has declined markedly, a trend USMCA’s implementation has not reversed”. The issues relating to corn and corn-based sweeteners are both political and cultural in nature (for both countries). Because of this, they are unlikely to be resolved without utilizing the tools available under the USMCA, including the dispute settlement process.

US- Mexico: seasonality

While issues over corn and biotechnology affect growers throughout the US and Mexico, the issues surrounding seasonality are localized in the United States to the East coast, and in particular growers in Georgia and Florida. Given differing growing seasons and market structures, producers in the U.S. West coast are not facing as steep competition from Mexican agricultural growers, and in fact have deeply integrated agricultural markets with Mexican producers, leading them to oppose the inclusion of seasonality protections during USMCA negotiations. An International Trade commission (ITC) investigation into trade damages for blueberries, released February 2021, found no evidence of damages. Reports on squash, cucumbers, strawberries, and bell peppers (set to be released in December 2021 and 2022, respectively) could result in a similar ruling. Despite these rulings, disputes over seasonality will continue to linger into the future. While the USMCA does not include seasonal produce protections, Florida Commissioner of Agriculture and Consumer Services (and democratic gubernatorial candidate), Nikki Fried, has suggested the US could bring a case against Mexico under USMCA if Mexican produce is sold at a lower price due to weaker environmental and labor standards. If the US moved forward with retaliatory measures, a tit for tat response from Mexico would be likely. Mexican Under Secretary for Foreign Trade Luz Maria de la Mora already indicated that Mexico would start a dispute settlement case if the US implemented trade barriers to seasonal produce. These responses would end up hurting other agricultural growers in addition to consumers.

Instead of moving towards this type of response, discussions about seasonality in the US should be framed in terms of potential win-win situations for both countries, as has successfully be done with regards to the countries’ avocado trade. According to a study from Texas A&M University, by increasing the availability of avocados to year-round access, the avocado industries in both the US and Mexico were able to expand demand for the product and raise prices. Similarly, increasing demand for berries and other agricultural goods by providing them year-round could benefit both growers in Mexico and on the East coast of the US. It’s also important to keep consumers as part of the potential beneficiaries of any policy, as they can either gain from increased access to cheap produce or lose when products become more expensive or less available.

The USMCA has the tools and mechanism available to address agricultural concerns so that the trade relationship between the three countries can be strengthened for the benefit of producers, workers, and consumers. To ensure this happens three key actions need to be taken: 1) the US needs to confirm a chief Agricultural Negotiator for the Office of the United States Trade Representative in order to fill out leadership at the USTR and provide a liaison who can serve as a primary advocate to solve key agricultural issues; 2) all parties must prioritize face-to-face meetings (with health considerations addressed) so that committees can effectively cultivate working relationships; and 3) if direct talks do not produce breakthroughs all parties should rely on the dispute settlement mechanisms provided in USMCA. If the US, Mexico, and Canada can successfully use the USMCA framework and processes to find solutions, the agricultural sector can shine as an example of the successes that can come from promoting freer trade across North America.

Author

Mexico Institute

The Mexico Institute seeks to improve understanding, communication, and cooperation between Mexico and the United States by promoting original research, encouraging public discussion, and proposing policy options for enhancing the bilateral relationship. A binational Advisory Board, chaired by Luis Téllez and Earl Anthony Wayne, oversees the work of the Mexico Institute. Read more

Canada Institute

The mission of the Wilson Center's Canada Institute is to raise the level of knowledge of Canada in the United States, particularly within the Washington, DC policy community. Research projects, initiatives, podcasts, and publications cover contemporary Canada, US-Canadian relations, North American political economy, and Canada's global role as it intersects with US national interests. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

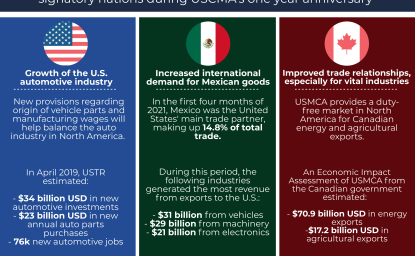

Infographic | USMCA at One

USMCA at One Year – Happy Birthday?