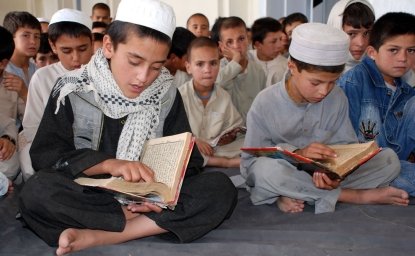

The Arab world has expanded educational enrollments faster than any other global region. The dramatic growth in student numbers supported by generous expenditures has not, however, delivered proportionate returns in quality or contributed to economic growth. Educational policy reforms, especially those supported by bilateral and multilateral aid agencies, typically focus on top-down technical solutions that overlook obstacles posed by national political economies. Too many internal initiatives primarily reinforce existing authoritarian orders rather than improve educational outcomes. In our new book, we identify obstacles to both internally and externally driven reforms resulting from Arab political economies and analyze prospects for greater success.

Just as economic privatization was subverted by cronies and their political patrons, today’s wave of education privatization is also likely to be captured.

Why reforms fail

Contemporary Arab education policy reflects neoliberal economic reforms adopted during the rising wave of globalization in the 1990s. Those top-down reforms were not intended by incumbent elites to truly liberalize political economies, but to preserve what Douglass North and his colleagues termed “limited-access orders,” by generating new resources for insiders. This resulted in stagnant crony-capitalist authoritarianism rather than dynamic, private sector-led economies.

Just as economic privatization was subverted by cronies and their political patrons, today’s wave of education privatization is also likely to be captured. As Christopher Davidson illustrates in our book, for example, US university-branch campuses in Gulf Arab states are intended by their government sponsors to serve more political than educational purposes. Adel Hamaizia and Andrew Leber explain that the Algerian and Saudi governments have sent vast numbers of students to universities abroad for the political reasons of providing patronage and deterring domestic radicalism rather than for acquiring skills needed for national development. Although not strictly a method of privatization, educating students abroad absorbs public resources that otherwise could be invested in domestic public educational institutions.

In poorer countries, such as Egypt, privatization is intended primarily to relieve budgetary burdens and to facilitate elite selection rather than to achieve pedagogical reform. Indeed, as we argue in this book, the Egyptian regime is intensifying its surveillance and control over private educational institutions, including their language of instruction, curricula, program offerings, and even their personnel, while also seeking to gain soft power and revenues from their presence.

In other words, education privatization is likely to create “crony students” dependent on the largesse of the state rather than endowing them with the means of achieving true political and economic independence.

Privatization, in sum, is likely to exacerbate educational shortcomings resulting from inequality. It will shore up limited-access orders through selective elite recruitment rather than by broadening minds and laying educational foundations for citizenship. In other words, education privatization is likely to create “crony students” dependent on the largesse of the state rather than endowing them with the means of achieving true political and economic independence. This is in fact the central finding of Calvert Jones’ investigation into the consequences of elite private education in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Other policies are unlikely to convert education systems into forces behind knowledge economies or liberalized political orders. Attracting donor support for public education seems intended to defray public criticism of ineffective government spending as much as it is to improve performance. If the latter, best practices such as enabling stakeholder participation and increasing autonomy to educational institutions would be more apparent. Disinterest in professionalization of educators, however, combined with efforts to subordinate them to central control, suggests that regimes do not want to empower stakeholders. This is true not just of primary and secondary school teachers, but also university faculty, as Florian Kohstall shows in his comparison of reform-seeking academic staff in Morocco and Egypt. The greater autonomy of university presidents and their institutions in Morocco, combined with more engagement with EU educational institutions, creates space where policy-focused professionals interact. But even in the relatively open Morocco, tentacles of centralization limit the influence of professionals and their organizations.

Preoccupation with political control is both widespread and harmful for education policies. The spread of computer-based teaching and learning—or EdTech—has the potential to upgrade student abilities, but also increase control over them and their instructors. Core curricular issues, such as the teaching of religion or language of instruction for minorities, have not been solved, reflecting governmental inability to address vital sociopolitical issues involved in education. Admiration for the putative Asian educational models, coupled with skepticism of traditional liberal ones, appears driven less by appreciation of pedagogical advantages than by the belief that it is more supportive of authoritarianism.

Crony capitalism has disempowered the private sector bourgeoisie, traditional advocates of quality education, while further weakening and subordinating public employees.

Like the content of education policies, the process by which they are made is also flawed. Merilee Grindle observes that not all stakeholders in education are decisionmakers, highlighting the overall infrastructural weakness of Arab states. Insiders refuse to empower outsiders by including them in decision-making even if their participation would improve outputs. Arab political economies have not generated class-based pressure on government to improve educational policy. Crony capitalism has disempowered the private sector bourgeoisie, traditional advocates of quality education, while further weakening and subordinating public employees. Unlike Latin America, the Arab world lacks meritocratic civil services and sidelines reformers within them from policymaking.

Finally, education in the Arab world is “de-regionalizing,” as proportionately ever fewer Arabs have educational experiences in other Arab countries. As nationalism supplants Arabism at this practical level, it opposes outside learning experiences that might then be applied “back home.” As Alisa Jones notes, the so-called “flying geese” model in East Asia, in which first Japan, then others including China and South Korea led the flock of states in their journey toward economic growth, was paralleled in education. There is no goose for other Arab states to follow in effectively reforming economic or educational policies. In sum, neither structural features of Arab political economies nor the making of policies are conducive to educational reforms. This begs the question: how will reform come about within existing orders?

Possible pathways to reform

There is a glimmer of hope in the decade-long series of Arab uprisings. They reflect dissatisfaction with the status quo, including with the quality of public services and the broken link between education and employment. Regimes are under enormous pressure to react to popular demand for such improvements. Several have embarked on cautious reforms intended to square the circle of preserving insider privileges while reducing popular discontent by improving access and quality. This could be a slippery slope down which partial reforms, once adopted, gain momentum that ultimately erodes the limited-access order’s hegemonic position.

At least in theory, educational reform is possible within the existing order, but with a caveat. In studies of democratization, such political shifts are typically caused by a crisis or rupture—such as economic breakdown, defeats in foreign wars, or political scandals—that compel actors in power to creatively rethink their existing approaches. The Arab uprisings in Algeria and Lebanon in 2019 and the 2020 pandemic are ruptures that revealed weaknesses in governance. In the past, the inadequacies of public services were deflected by appeals to nationalism, the struggle against Israel, or to religious commitment. Now, however, demand for improved and equitable service delivery has largely supplanted vague ideological concerns. The push for public-service reform is likely to intensify, driven by economic and demographic realities including urbanization, competition for private sector employment, gender equality, and the digitization of communication.

Some insiders may ultimately decide that reform is the safest response to ever-growing pressure for change, thus opening the door to coalitions with outsiders.

A related factor might be the awareness of performance on international assessments. Up to now, the various global measures of educational achievement such as PISA, TIMSS, or the rankings of the world’s top 500 universities, have largely passed unnoticed by Arab publics. But that is changing as these rankings appear more frequently in global media. Some insiders may ultimately decide that reform is the safest response to ever-growing pressure for change, thus opening the door to coalitions with outsiders.

Developments already under way may also contribute momentum to educational reform. As Kohstall has pointed out, in Egypt and Morocco bilateral and multilateral donors can and do foster change within education systems. It is possible such leverage will intensify as donors become more dissatisfied with recalcitrant governments or those regimes grow more fearful of public demands for reform. Donors and implementers, moreover, are not all multilateral behemoths. They also include a network of smaller private organizations that sponsor relatively unobtrusive projects, but whose aggregate contribution provides appropriate models for reform. However, the Soros Foundation’s support for tertiary education in Eastern Europe and regime reactions against it illustrate the potential for backlash against such undertakings.

Educational innovations introduced by external actors but embraced by Arab governments may have unintended consequences. EdTech, though embraced by Arab governments partly for its potential to control education systems and lower costs, may also have liberating effects for students and their instructors. Among these effects could be reduced reliance on rote learning, on canonical texts, and on centrally authorized sources in general. In their stead, more horizontal, user-guided learning techniques could flourish, thereby challenging vertically structured educational and political systems.

Privatization might have a similar, equally unintended liberating effect. Arab regimes are seeking to square the circle of encouraging privatization while ensuring control of that sector. It can be reasonably predicted that those involved in private sector education will chafe at government intrusions into their systems. In sum, regime intent to improve educational systems while maintaining, even enhancing control over them, may prove to be a contradictory undertaking.

The views expressed in these articles are those of the authors and do not reflect an official position of the Wilson Center.

Authors

Middle East Program

The Wilson Center’s Middle East Program serves as a crucial resource for the policymaking community and beyond, providing analyses and research that helps inform US foreign policymaking, stimulates public debate, and expands knowledge about issues in the wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Read more

The MENA Workforce Development Initiative

The Middle East and North Africa Workforce Development Initiative (MENA-WDI) aims to assess both current and projected challenges facing the region in developing the workforce and the implications for peace and stability. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

How Education Can Empower Young Women in MENA