Event Report and Transcript: Assessing Warsaw Pact Military Forces

A transcript of the CWIHP Event "Assessing Warsaw Pact Military Forces: The Role of CIA Clandestine Reporting" and event report written by moderator A. Ross Johnson.

To read the transcript, please click here.

Only twenty five years ago, Europe was divided into opposing camps buttressed by military forces of NATO and the Warsaw Pact -- the most lethal concentration of opposed military forces in close proximity in peacetime in human history. The United States and its NATO allies devoted vast resources to analyzing the capabilities, strategy, and tactics of Warsaw Pact forces intended for use in military conflict in Europe. U.S. and NATO intelligence agencies drew on many sources to provide policymakers and military planners with their assessments. These included public or open source discussions, signals intelligence, overhead imagery, defense attaché reporting, and clandestine reports from Soviet and East European military and civilian "insiders," both defectors and agents in place.

The Wilson Center’s Cold War International History Program convened on January 16, 2014, a discussion of the role of intelligence derived from clandestine human and technical sources in the Central Intelligence Agency’s analyses of Warsaw Pact military capabilities for war in Europe from 1955 to 1985. This meeting was a sequel to a 2011 Wilson Center discussion of Soviet control mechanisms within the Warsaw Pact also based on CIA human intelligence reporting. The January 2014 meeting was one of a series of CWIHP publications and discussions that have focused on the external capabilities and internal dynamics of the Warsaw Pact drawing on new documentary evidence.

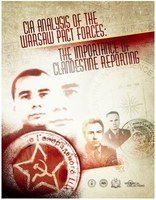

The January 2014 discussion was based on public release by CIA of a large tranche of internal Warsaw Pact classified documents and other information obtained clandestinely and translated and disseminated by CIA to senior U.S. policy makers. These intelligence reports were utilized to assess the political and military balance in Central Europe between the Warsaw Pact and NATO during the Cold War. The collection, consisting of some one thousand newly released documents and some five hundred previously released items, numbering some 25,000 pages, is available online and on an interactive DVD available from the Government Printing Office.

This document release augments earlier CIA releases on the Warsaw Pact Wartime Statutes, on preparations for martial law in Poland, and other aspects of Soviet military affairs available at the CIA's FOIA Electronic Reading Room. Mark Kramer, Director of the Cold War Research Project at Harvard University, characterized the new documentary release as "an extraordinarily important collection for people who are interested in the Warsaw Pact, and Soviet military planning, in all aspects of Soviet East European relations." Barry Watts, a veteran military operations analyst, recalled his earlier experience as an Air Force fighter pilot and member of the Department of Defense Checkmate team when he found CIA technical assessments more useful than those provided by Air Force Intelligence.

The latest tranche of released CIA documents were introduced at the Wilson Center discussion by Joan Bird and John Bird, both retired CIA analysts of Soviet military affairs who led CIA’s effort to select and declassify the documents. Joan Bird explained the provenance of the documents. Once obtained by CIA from human sources that included Soviet Colonels Pyotr Popov and Oleg Penkovsky and Polish Colonel Ryszard Kuklinski, they were translated and circulated to a very narrow set of senior policymakers in order to protect the identity of the Soviet and East European individuals who provided the information. This category of intelligence reports differed from information provided by low-level defectors and refugees, which was routinely distributed to a much wider circle of U.S. officials. Not all relevant documents are included in the release; specific reports that the Birds recalled reading as analysts could not be located in the archives. The human source intelligence reports in the new collection are complemented by reports from clandestine technical intelligence sources and by synthetic analyses including National Intelligence Estimates that incorporated the essence of the clandestine reporting without detail that might reveal the source.

The high-level intelligence reports indicate the date of the original document and the date of dissemination of the translation to policymakers. Documents were sometimes obtained only years after their original date, and the volume of material after the 1950s sometimes delayed translation. A 138 page Soviet military manual was distributed in translation fourteen years after the original was published. (Document VII-100) In other cases, the process was much quicker. An intelligence report on an April 1978 Warsaw Pact military exercise was distributed in translation on November 17, 1978. (Document VII-103) Mark Kramer had compared selected translations with original Russian and Polish documents now available from former Soviet bloc archives and reported that some translations were flawless, others problematic, but none that he reviewed so flawed as to distort the meaning.

Reviewing the content of the released CIA documents, John Bird pointed to a number of examples that informed CIA analysts and U.S. policymakers about Soviet and Warsaw Pact military capabilities. (Additional examples are given in the Bird’s paper introducing the documents are available here). Popov provided a copy of the Soviet Field Service Regulations issued in 1949 and still in use in the early 1950s (Document I-20) that ignored the use of nuclear weapons in line with Stalin’s reliance on massive conventional forces at that time. During the 1961 Berlin crisis Penkovsky provided current information on the reluctance of the Soviet High Command to see the crisis escalate, fearing a major conflict for which they were not ready – information conveyed personally to President Kennedy by CIA Director Allen Dulles. Penkovsky also supplied a copy of the updated Soviet Field Service Regulations of March 1959 (Document III-3), which envisaged the use of nuclear weapons in a European conflict. Penkovsky also provided serial copies of the top-secret edition of the periodical Military Thought that contained an ongoing discussion among top Soviet military planners about the role of theater nuclear forces.

Human sources were complemented by overhead imagery. Photographs from U2 airplanes and early Corona reconnaissance satellites, supplemented by human reporting, provided a comprehensive picture of Soviet forces in Cuba during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis – the first movement of an expeditionary Soviet Group of Forces outside the Soviet Union since World War II and a snapshot of how Soviet forces would be constituted in wartime. Later in the 1960s, higher-resolution satellite imagery coupled with information on Soviet force structure provided earlier by Penkovsky gave U.S. decisionmakers a more realistic assessment of Soviet military capabilities than the inflated numbers of Soviet intercontinental missiles and Soviet combat divisions contained in earlier National Intelligence Estimates. In the 1970s, human and technical sources enabled CIA to provide detailed information on classes of Soviet and East European weaponry to senior American officials engaged in the first conventional arms control negotiations (Mutual and Balanced Force Reduction talks) with their Soviet counterparts. By then, John Bird noted, the challenge for the analyst was not too little but too much information, requiring careful screening to focusing on what was truly important.

Barry Watt cited the example of realistic CIA appraisals of the capabilities of SU-24 (Fencer) Soviet all-weather attack aircraft introduced in the mid-1970s, based on clandestine human and technical sources, which indicated a combat range of less than half that estimated by the Air Force Foreign Technology Division at the time.

Mark Kramer noted that the released CIA documents, although prepared to inform policymakers at the time of original distribution and now dated, still help us clarify important aspects of Warsaw Pact history. He cited the example of Marshal Zhukov’s remarks to the commanders of the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany in March 1957 (Document I-39) on Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Revolution. Zhukov said that Soviet forces initially withdrew from Budapest because of loses their one division incurred at the hands of the Hungarian fighters before returning in force to suppress the Revolution. Zhukov’s remarks also illuminated the offensive nature of Soviet military planning for war in Europe, including the use of nuclear weapons, and a decision at that time to deny the emerging East German army still viewed as not fully reliable the use of up-to-date Soviet weapons systems. A second example of the value of the documents as a historical source is the detailed series of reports on the numbers and capabilities of Soviet tactical nuclear weapons deployed in several East European countries.

The series of CIA document releases complements other once-secret materials on the Warsaw Pact from East European military archives that have become available over the past twenty-five years thanks to the efforts of CWIHP, the Parallel History Project, the declassification initiative of Polish Defense Minister Radek Sikorski, and others. The released CIA documents are valuable for historians of the Cold War on two grounds – first, for what they tell us about the CIA’s understanding of the Soviet-East European military complex at the time, and second what they add to our knowledge today of the Warsaw Pact, especially given the inaccessibility of Soviet military archives.

Documents & Downloads

About the Author

A. Ross Johnson

Senior Adviser, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty; former Director, Radio Free Europe

Before his passing in February 2021, A. Ross Johnson was a Wilson Center History and Public Policy Fellow and Senior Advisor for Archives at RFE/RL. He was a former director of Radio Free Europe.

Read More

Cold War International History Project

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Through an award winning Digital Archive, the Project allows scholars, journalists, students, and the interested public to reassess the Cold War and its many contemporary legacies. It is part of the Wilson Center's History and Public Policy Program. Read more

History and Public Policy Program

The History and Public Policy Program makes public the primary source record of 20th and 21st century international history from repositories around the world, facilitates scholarship based on those records, and uses these materials to provide context for classroom, public, and policy debates on global affairs. Read more