Eastern Europe and Cuba: The Missile Crisis, the Soviet Empire Retreats Back

How diplomats from Eastern Europe reported on the Cuban Missile Crisis and its aftermath.

A blog of the History and Public Policy Program

How diplomats from Eastern Europe reported on the Cuban Missile Crisis and its aftermath.

The deployment of Soviet medium-range missiles only 90 miles from Key West in 1962 brought the world as close as ever to a superpower nuclear conflict. Unsurprisingly, the Cuban Missile Crisis attracted immense interest by contemporary students of international affairs and subsequently by Cold War historians.

After the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, new evidence from Soviet archives as well as from Eastern Europe highlighted Khrushchev’s original explanation for sending medium-range missiles to Cuba. Accordingly, in 1961, a Soviet embassy report painted a very dire situation on the island with US-backed counter-revolutionary forces gaining momentum.[1]

The interruption of diplomatic relations with the US in January 1961 brought the immediate danger of military aggression against Cuba, the head of the Czechoslovak intelligence observed.[2] At the same time that Cuba’s security prospects waned, Havana’s economy also worsened. To signpost the urgent need for tangible support for the new Cuban regime, Czechoslovak diplomats in Havana informed Prague of the Soviet envoy’s admission that the threat of US-sponsored counter-revolution left Castro with no other choice but to turn to Marx and Lenin and to rely on the help of the Soviet Union and the other socialist countries.[3]

Amid the rapidly changing situation in Cuba, with the new regime’s turn to the left and the perceptible US threat, Khrushchev decided to launch the transatlantic transfer of the missiles in utmost secrecy, keeping even the East European socialist leaders in the dark. The Soviet Party chief’s brash initiative confused the other socialist states. According to the Polish ambassador, Moscow’s goal to install missile launchers in Cuba was not completely clear. The explanation given by the Soviet Deputy Premier Sergei Mikoyan that Moscow wanted to use the missiles to obtain a guarantee for Cuba had obvious holes, Jeleń argued. To him, the Soviet move seemed more like a political ploy than military strategy. Warsaw’s emissary in Havana concluded his critical observations by stating that the Soviet Union did not make a mistake in withdrawing the missiles as the Cubans suggested but rather by installing them in the first place.[4]

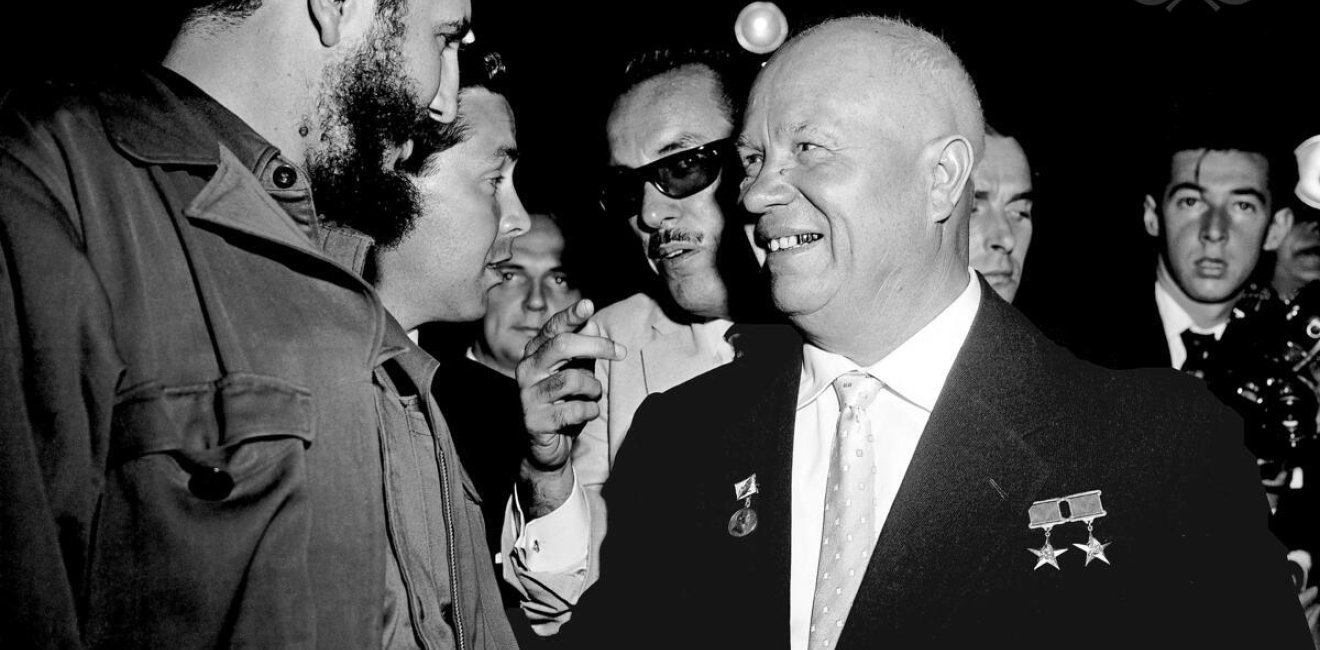

While East European leaders felt sidelined by Khrushchev, Eastern European diplomats felt ignored by the Cuban authorities during the crisis. The Soviet ambassador, Aleksandr Alekseev, however, enjoyed close relationships with the Cuban leadership, allowing him not only to take the central stage in the events but also to provide valuable insights as to the origins of Castro’s disagreement with the Kremlin’s management of the crisis. As a Polish dispatch noted, this could not be said for Alekseev’s predecessor, Sergei Kudryavtsev, who failed to develop a sufficiently close relationship with Castro personally.[5] According to another Polish report, Kudryavtsev’s dismissal was made at Fidel Castro’s explicit request, showing the Cuban leader’s hands-on approach in his dealings with the Revolution’s new friends. [6]

The way the crisis was resolved between Kennedy and Khrushchev without Fidel Castro being closely involved incensed the sensitive Cuban leader, highlighting his fear of Cuba’s subjugation. An Albanian party report testified to the worsening Soviet-Cuban relations in the wake of the missiles’ withdrawal, zeroing in on the “enraged” Fidel, who believed the Soviet leader treated Cuba not as a socialist country but as a satellite state.[7]

A decade later, Fidel’s brother, Raúl, shared in a very frank conversation with the Bulgarian leader Todor Zhivkov that at a Politburo meeting of the Cuban Communist Party, without specifying when Fidel admitted that Khruschev’s approach was correct as Moscow’s objective for Cuba “to exist and continue to exist” was fulfilled. According to Fidel, the Soviets were right then because “Cuba still exists now.” Arguably, with this admission, Fidel Castro had forgiven Moscow for a difficult chapter in Cuba’s relations with the Soviet bloc.[8]

Information of the Soviet Ambassador in Cuba on 18 April, 1961

Bolesław Jeleń, 'Information Note', 1962 December 13

Bolesław Jeleń, 'Memo to Department VI [Latin America]', 1962 August 14

Information on the Situation in the United Revolutionary Organizations of Cuba, 1962

Stenographic Protocol of the Meeting between Todor Zhivkov and Raul Castro Rus, 1974 March 11

[1] [undated document from Soviet Embassy in Cuba requesting Soviet support against “counter-revolutionary gangs”] c. April 1961, NAČR, ÚV KSČ, Antonín Novotný – Zahraničí, Karton 121, Komunistická strana Kuby

[2] J. Miller, “Nebezpečí vojenské agrese proti Kube a návrh na další opatření čs. rozvědky na podporu revoluční Kuby” [The danger of military aggression against Cuba and a proposal for further measures of Czechoslovak intelligence in support of revolutionary Cuba], 6 January 1961, Archiv Bezpečnostních Složek [Security Services Archive] (ABS), RN 80618 I.S SNB, p. 3 [39].

[3] "Informatsiya sovetskogo posla iz Kubȳ ot 18 aprelya" [Information of the Soviet ambassador in Cuba on 18 April], n.d. (c. 1961), NAČR, ÚV KSČ, Antonín Novotný – Zahraničí, Karton 121, Komunistická strana Kuby, p. 1. See also Minutes of Conversation: Gustáv Husák and Fidel Castro, 22 June 1972, NAČR, KSČ-ÚV 1945-1989, Praha - Gustáv Husák, k. 376, p. 11/1 ž.

[4] Bolesław Jeleń, "Notatka informacya" [Information note], 13 December 1962, Archiwum Ministerstwa Spraw Zagranicznych [Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs] (AMSZ), D. VI, 1962, Blokada Kuby, 52/65, W-5, pp. 2-3 [3-4].

[5] Bolesław Jeleń [Memo to Department VI [Latin America]], 14 August 1962, AMSZ, D. VI – 1962, Kuba, 52/65, W-4, p. 3

[6] A. Krajewski, "Ocena pozycji Polski na Kubie w okresie wizyty min. Rapackiego, dokonana na podstawie rozmów, które przeprowadziłem w Hawanie po Jego wyjeździe” [Assessment of Polish position in Cuba during the visit of Minister Rapacki, based on the conversations I had in Havana after his departure] draft, 2 July 1962, AMSZ, D. VI – 1962 Kuba, 52/62, W-4, p. 1.

[7] “Të dhëna mbi gjedjen në organizatat e bashkuara revolucionare të Kubës” [Information on the situation in the United Revolutionary Organizations of Cuba], n.d. [c. 1962], Drejtoria e Përgjithshme e Arkivave [General Directorate of Archives] (DPA), f. 14, l. 3/1, d. 7, p. 3.

[8] Memcon, Todor Zhivkov - Raúl Castro, 11 March 1974, Tsentralen Dyrzhaven Archiv [Central State Archive] (TsDA), f. 1B, op. 60, a.e. 142, p. 5.

A leader in making key foreign policy records accessible and fostering informed scholarship, analysis, and discussion on international affairs, past and present. Read more

The Cold War International History Project supports the full and prompt release of historical materials by governments on all sides of the Cold War. Read more

The Nuclear Proliferation International History Project is a global network of individuals and institutions engaged in the study of international nuclear history through archival documents, oral history interviews, and other empirical sources. Read more