In 2022, the major news centered on leadership transitions in both al Qaeda and ISIS. The turbulence at the top, however, was not matched by drastic changes or new advantages on the battlefield. Both activities of both movements generally followed the patterns of 2021, though some notable developments indicated possible future changes.

Al Qaeda Leadership

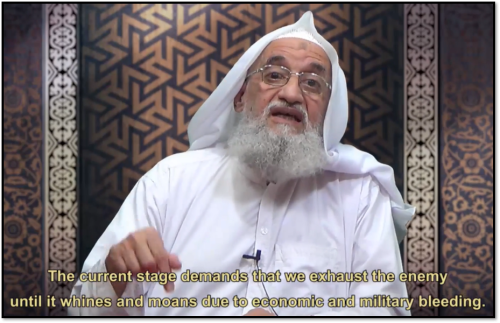

On July 31, Ayman al Zawahiri was killed when the United States fired a pair of Hellfire missiles as the al Qaeda leader stood on the balcony of his apartment in Kabul, where he had been living for several months with the support of the Haqqani network, a radical faction of Afghanistan’s Taliban. Zawahiri, a septuagenarian Egyptian doctor and a major al Qaeda ideologue, had succeeded Osama bin Laden, who died when U.S. special operations forces raided his home in Pakistan in May 2011. The new emir was reportedly Saif al Adel, an Egyptian in his sixties based in Iran. But by the end of 2022, al Qaeda had still not acknowledged the death of al Zawahiri or announced his replacement.

Al Qaeda’s silence on succession raised questions about the health of the organization. Zawahiri’s tenure was considered by some analysts to have been fairly successful, since he kept al Qaeda from falling apart during the meteoric rise of ISIS, a breakaway that became its main rival among Sunni jihadis. Zawahiri also lived to see al Qaeda’s Taliban allies return to power in Afghanistan in 2021. But he actually left behind an organization in disarray.

Zawahiri was known largely for his books and recorded statements. Most were long and tedious—uninspiring even for his jihadi admirers. As a commander, he was unable to compel obedience and guide events on the battlefield. In 2013, he sought to prevent the rise of ISIS by ordering Abu Bakr al Baghdadi to return to Iraq and not interfere with Jabhat al Nusra, the Syria-based affiliate of al Qaeda. Baghdadi refused to obey, and subsequently his forces swept through Syria and Iraq to create a caliphate—and become al Qaeda’s main jihadi rival. Zawahiri disavowed Baghdadi in 2014.

Zawahiri’s presence in Kabul in 2022 indicated that the Taliban—or at least the Haqqani faction of it—was once again hosting al Qaeda in direct violation of the U.S.-Taliban accord reached in February 2020. Since their return to power, Taliban leaders have routinely lied about the presence of al Qaeda members and leaders on Afghan soil; it has clearly supported some of them. On the other hand, the international community had evidence that the Taliban restricted some al Qaeda activities in Afghanistan and that the terrorist group has not been able to regroup. In July 2022, a U.N. team that monitors sanctions reported that the Taliban had prohibited al Qaeda from plotting external attacks from Afghan soil. Al Qaeda also did not appear to rally jihadis from around the world to come to the Taliban’s “Islamic emirate” to create a jihadi safe haven, as it had in the 1990s. In August, National Security Council spokesperson Adrienne Watson claimed that al Qaeda had not reconstituted in Afghanistan. She said less than a dozen al Qaeda core members were in Afghanistan. In November, Christine Abizaid, director of the U.S. National Counterterrorism Center, testified that the United States had “no indication” that the al Qaeda core in Afghanistan was involved in plotting external attacks. By the end of 2022, U.S. officials were adamant that the threat to the U.S. homeland from al Qaeda was minimal.

So predictions of an al Qaeda revival after the Taliban returned to power were not borne out. Although Al Zawahiri was gone, al Qaeda would not admit it, perhaps out of fear of embarrassing the Taliban. Nor would al Qaeda publicly name a successor. All of this could reflect either al Qaeda’s heeding the orders of the Taliban or concern with the fact that the most likely successor, Saif al Adel, was in Iran. His presence in a predominantly Shiite country was problematic since Iran was viewed by rank-and-file Sunni jihadis to be a political and religious rival.

Al Qaeda Branches

The various factions in the broader al Qaeda network have not ceased functioning even as the future of al Qaeda leadership remained a major question. The branches or affiliates were local jihadi groups that previously pledged loyalty to al Qaeda but in many ways were independent actors. They were broadly aligned with al Qaeda strategically and ideologically, but for the most part carried out missions against local enemies in view of eventually establishing their rule. The decentralized nature of the al Qaeda network suggested that al Zawahiri’s death will not significantly impact the network’s overall functioning.

The most successful al Qaeda affiliates were in Africa — al Shabab in Somalia and Jamaat Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) in the Sahel. In 2022, both were dynamic and dangerous organizations that posed major security challenges in their areas and beyond. JNIM was technically a subordinate faction of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghrib (AQIM), which was al Qaeda’s North African franchise. AQIM previously carried out terrorist attacks mainly in Algeria, but for several years it has struggled to rebuild since increased counterterrorism pressure between 2013 and 2018 led to the death of some 600 fighters. To the extent that it continued to have influence, it was via JNIM.

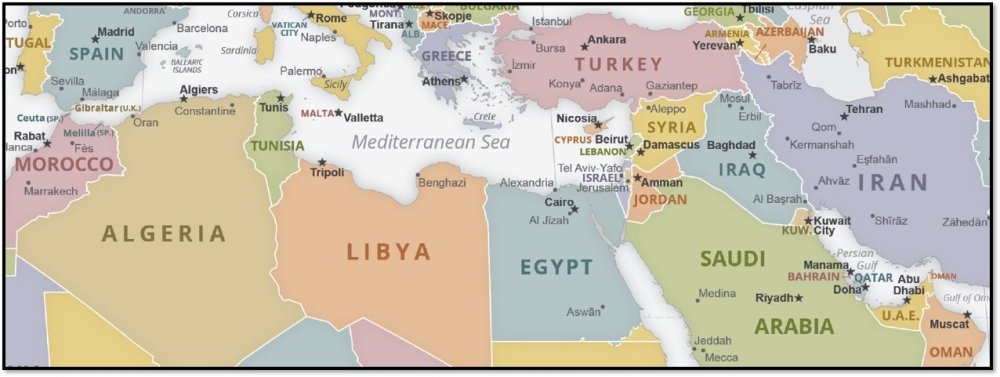

In the Middle East, by comparison, al Qaeda did not fare well in 2022. Its strongest affiliate had been Jabhat al Nusra from 2013 until 2016. But in 2016, it left al Qaeda and later changed its name to Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS), which has ruled much of Idlib Province since 2017. When Jabhat al Nusra left al Qaeda, some al Qaeda loyalists in Syria formed a new affiliate called Hurras al Din. It was initially highly active, but HTS later clamped down on its activities and arrested some of its members and leaders. By the end of 2022, Hurras al Din appeared to be defunct.

The most significant affiliate in the Middle East was Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) based in Yemen since 2009. The U.N. team monitoring sanctions put AQAP’s strength at “a few thousand fighters.” In her November testimony, Abizaid, the NCTC director, said that AQAP was still “intent on conducting operations in the West and against U.S. and allied regional interests.” Yet AQAP has also faced setbacks in recent years due to U.S. counterterrorism operations combined with the chaos of Yemen’s civil war. In 2022, it still carried out sporadic attacks on the other combatant parties in Yemen’s civil war, including the Yemeni and the Houthi rebels. But AQAP was not a driving force in the conflict. It no longer tried to control territory and had lost much of its popular appeal.

ISIS Leadership

ISIS also experienced leadership turnover in 2022, although it did not shy away from acknowledging the losses. On February 3, Abu Ibrahim al Hashimi al Qurashi, the pseudonym of Amir Muhammad Said Abdal al Rahman al Mawla, was killed in a U.S. special forces raid on his compound in Atmeh, Syria, a town along the border with Turkey. The ISIS spokesperson was also apparently killed around this time. A month later, the new ISIS spokesman announced that Abu al Hasan al Hashimi al Qurashi was the new caliph.

On November 30, ISIS announced that Abu al Hasan had recently been killed in battle. A CENTCOM statement reported that he had been killed by Syrian rebels in the southern province of Deraa in mid-October. Abu al Hasan had lasted little more than eight months. The new caliph was Abu al Husayn al Husayni al Qurashi. Yet while little was known of his background or identity, Abu al Husayn reportedly belonged to a new and younger generation of ISIS leaders. The first generation—which came of age during the U.S. occupation of Iraq (2003 to 2011)—appeared to be passing the torch to younger men whose experience began with the rise of ISIS in 2013-14. Abu al Husayn was “not from the original team,” a U.S. military official told Voice of America. The leadership transition showed that “there are people who are trained and ready to come behind them,” the official said.

After the loss of each caliph, ISIS has orchestrated propaganda photos showing hundreds of ISIS fighters—from Syria to Afghanistan, and from Egypt to Mozambique—swearing allegiance to the latest caliph. ISIS has not personalized the caliphate by focusing on the leader. By the end of 2022, there were no significant signs of dissent or dissatisfaction within the global ISIS network. Yet having to announce the loss of two caliphs in a year is probably unsustainable.

ISIS suffered other losses in 2022. At least six other senior ISIS officials were reportedly either killed or detained after Abu Ibrahim’s death.

ISIS Provinces

Even with the loss of leaders, the various provinces in the global ISIS network remained active from Africa to Central Asia in 2022. The largest number of ISIS operations have shifted south toward Africa in recent years. In 2022, ISIS boasted several “provinces”—or wilayat in Arabic— in sub-Saharan Africa, including in Nigeria in west Africa, Mali in the Sahel, the Democratic Republic of the Congo in central Africa, and Mozambique in southern Africa. It also boasts a particularly active franchise in Afghanistan along the Pakistan border known as ISIS-Khorasan Province or ISIS-K.

Unlike al Qaeda, ISIS still had a strong presence in 2022 in the Middle East, particularly Iraq, Syria, and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. ISIS released a weekly newsletter called al Naba documenting insurgent attacks in its various provinces. The pace of attacks was somewhat lower in Syria and steeply down in Iraq compared with previous years.

In 2021, ISIS averaged 84 attacks and 148 casualties per month in Iraq, while it claimed an average of 38 attacks and 64 casualties per month in 2022, according to al Naba. Attacks in Iraq consistently declined in 2022, despite an upsurge during Ramadan. The cause—whether due to leadership deaths, the effectiveness of Iraq’s counterterrorism operations, or the movement running out of steam—was unclear. The next year may reflect whether 2022 was an anomaly or the start of a trend.

In Syria, attacks in 2022 were also down compared to 2021, though not to the degree in Iraq. In 2021, ISIS averaged 29 attacks and 70 casualties per month in Syria, while it claimed an average of 21 attacks and 58 casualties per month in 2022. The attacks were largely in central Syria and the Euphrates River valley. The most noteworthy ISIS operation was a January attack on a prison controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a U.S.-backed militia in northeast Syria. The prison assault led to a 10-day battle between ISIS and the SDF that freed dozens of ISIS detainees but ended up killing hundreds of ISIS fighters and dozens of SDF forces. The clash renewed attention to the thousands of ISIS detainees held since the collapse of the caliphate in 2019. ISIS has long sought to free prisoners and beef up its dwindling numbers.

In Egypt’s Sinai, ISIS was an enduring problem in the mostly uninhabited desert areas near the border with Israel, despite coordinated Egyptian and Israeli operations against it. In 2021, ISIS averaged 9 attacks and 17 casualties per month, while it claimed an average of 7 attacks and 19 casualties per month in 2022, according to al Naba.

Author

The Islamists

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

What Trump’s 2025 Inauguration Speech Says About US-Mexico Policy