El Salvador has become the most violent place on earth. The country’s security situation has dramatically deteriorated in recent months, with homicide rates skyrocketing over the summer to levels unseen since the country’s civil war. The wave of violence peaked in August, with over 900 homicides in one month. The homicide rate for 2015 will almost certainly exceed 100 per 100,000 individuals, compared to 68.6 in 2014 and 43.7 in 2013, according to El Salvador’s Institute of Legal Medicine (IML) and National Civil Police (PNC).

Though it remains unclear whether criminal gangs, transnational organized crime, the government’s own tactics, or other actors are driving the violence, the government continues to state that a majority of the homicides result from in-fighting between the Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18 gangs. A recently-published report from El Salvador’s Attorney General attributes 65 percent of homicides to the gangs, despite police evidence that the number might be 35 percent.

Regardless of who is behind this unprecedented uptick in violence, the state has struggled to gain control of the situation. Though the government of President Salvador Sánchez Cerén has recently launched El Salvador Seguro (Secure El Salvador), an ambitious security plan emphasizing prevention and rehabilitation, its implementation has been overshadowed by the uptick in violence and a subsequent return to repressive security measures. Thus, despite the de jure policy of prevention and rehabilitation, the de facto policy has prioritized direct confrontation with the gangs using police and military forces. These confrontations have in turn led to large-scale indiscriminate arrests, which have been proven to do little to stem the violence.

The skyrocketing violence has serious consequences for migration, economic growth, governance, and Salvadoran democracy itself. Though the number of homicides has eased off its high from last summer, violence remains unacceptably high and the gangs and the state remain locked in a stalemate with no end in sight. Here, we examine how this situation arose, the government’s response, and prospects for the future.

- The failure of the 2012 gang truce heavily influenced the current situation: To understand why violence has escalated in El Salvador, we have to return to March 2012 when a truce was signed between the Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18 leadership, with the tacit support of the Salvadoran government, then led by President Mauricio Funes. The truce emerged when the Funes government, understandably anxious to lower a ballooning homicide rate, engaged in dialogue with gang leaders through trusted mediators. The dialogue led to an agreement and eventually a de facto truce when the government transferred gang leaders from maximum security prisons to lower-security facilities. This was done ostensibly so gang leadership could enforce the truce. While the truce initially cut homicides by half, it did not stem extortions and other criminal activities and thus remained largely unpopular among many Salvadorans. Secretive negotiations with gang leaders and the widespread belief that the government had offered benefits to imprisoned gang leaders in exchange for a reduction in homicides undermined the public’s trust in the truce. By the end of its first year in March 2013, more than half of Salvadorans had a negative opinion of the truce, even though the homicide rate remained comparatively low. By the end of its second year in March 2014, most experts and Salvadorans agreed that the truce was dead. It should also be noted that during this time U.S. policy was strongly and vocally opposed to the truce.

While the truce experiment enjoyed a short period of surprising success, it lacked a sustainable foundation and ultimately opened the possibility for the astronomical levels of violence today. The truce was negotiated from a place of desperation on the part of the Funes government, leaving some with the impression that gangs could use violence as a potent political tool to force the government into negotiations. For many, the truce implied that the gangs had gained recognition as legitimate political actors whose greatest negotiating leverage came from the violence they could unleash. In this view, once the gangs created enough chaos, the government would make concessions, including transferring gang leaders to lower security prisons and allegedly even paying them to maintain the truce. When the truce faltered and later collapsed, the gangs would use the political capital the truce had given them to attempt to force the government back to the table.

- The return to repressive policies has exacerbated the situation: President Sánchez (who is from the same left-of-center political party (FMLN) as Funes), took office in June 2014 promising a different approach to the gangs than his predecessor. In January 2015 he clarified that he would not pursue further negotiations with the gangs. Instead, he decided to pursue a starkly different policy of confrontation with the gangs that has inevitably off a cycle of escalation and brinkmanship between the gangs and the state.

The government sent gang leaders back to maximum security prison in mid-January. Around the same time, government rhetoric began emphasizing “going to war” with the gangs, a stark departure from the dialogue President Funes had supported. The director of the PNC, Mauricio Landaverde, underscored this shift when he said that “All members of the PNC that have to use weapons against criminals due to their work as officers should do so with complete confidence. The PNC and the government will protect them.” Accompanying this shift in language was an uptick in extrajudicial killings, some attributed to death squads and others attributed to the police forces themselves. Around the same time, the gangs began targeting law enforcement personnel and have killed over 50 police officers and 16 soldiers so far this year. In May, the President sent 600 additional soldiers in three military battalions to patrol the streets alongside the police, further exacerbating the atmosphere of militarization in the country. In July, the gangs responded by enforcing a public transportation strike that paralyzed the streets of San Salvador. In August, the Salvadoran Supreme Court approved a law labeling the gangs as well as their “collaborators, apologists, and financiers” as terrorists, permitting longer prison sentences and lessening the burden of proof in criminal cases.

The new terrorist designation has facilitated more aggressive government crackdowns on suspected gangs. Joint police-military units have conducted indiscriminate arrests of as many as 200 youth at once for alleged “acts of terrorism.” In many cases, those arrested are later released or remain in pre-trail detention for an extended period of time.

Though aggressive policies such as those described above do little to dismantle the gangs in the long term, they remain politically popular with Salvadorans who are eager to see a government “do something” to fight the gangs. According to a recent poll by Salvadoran newspaper La Prensa Gráfica, 72.1 percent of Salvadorans believe that insecurity is the principal problem facing the country, up over 10 percent from 2014. Given such high levels of concern with insecurity, arrests of hundreds of individuals may appear more impressive than a targeted arrest of a single gang leader. These massive arrests give off the impression of a government that is winning the “war against the gangs” despite the fact that government and police leadership itself has acknowledged that repression alone is not an effective long-term strategy. Such policies simply grab low-hanging fruit while doing little to tackle gang leadership or prevent, rehabilitate, and reinsert existing gang members.

- The government is also pursuing an ambitious prevention and rehabilitation plan: While hardline security measures have dominated the government’s policy toward gang violence this year, the government has also developed an ambitious plan prioritizing prevention, rehabilitation, and reinsertion. The government recently launched El Salvador Seguro (Secure El Salvador), a multi-year, $2.1 billion dollar plan to tackle citizen security issues. The ambitious plan, developed by the National Council on Citizen Security and Coexistence (CNSCC) includes an action plan with 124 recommendations to improve the security climate. Violence prevention is the centerpiece and will receive nearly 75 percent of the plan’s funds if fully implemented and funded. A second component of this plan is a proposed reinsertion law which offers educational opportunities, job creation, and drug addiction therapy for gang members who have not committed serious crimes and are willing to renounce their gang affiliation. This law is currently under consideration in the Legislative Assembly’s Security Commission.

The question of course remains whether or not the government will be able to pay for such an ambitious plan. Though the government has taken important steps to fund the El Salvador Seguro plan, they are still far away from their $2.1 billion goal. In recent months the government acquired $100 million in loans to support these programs and passed a new 5 percent telecommunications tax intended to defray the plan’s costs. President Sánchez has also suggested that he hopes the United States will contribute, along with various state institutions, the private sector, and individual donors. Nevertheless, with a gang population of more than 60,000, according to 2012 estimates by the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, it will be a challenge to come up with enough money to implement the rehabilitation law, not to mention the $2.1 billion needed for El Salvador Seguro.

In addition to El Salvador Seguro, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has funded a number of community-based prevention strategies as a part of the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI). Specific programs, with funding totaling more than $88.2 million from 2012 to 2018, include 118 community youth centers, vocational training in 55 municipalities, youth and family workshops in conflict prevention, and 25 victims’ assistance centers that in 2014 alone helped more than 10,000 victims of gender-based violence. This prevention work, which crosses multiple sectors in education, economic growth, employment, public health, and governance, has had a demonstrated impact in reducing crime and increasing citizens’ sense of security. Furthermore, these programs represent the majority of U.S. security assistance to El Salvador. In 2015, the United States spent nearly $3 on humanitarian and development aid to every $1 spent on military and police aid.

Efforts at prevention and rehabilitation, encouraging as they might be, continue to be overshadowed by shocking levels of violence and the bellicose rhetoric of “war” favored by the Salvadoran government.

- The situation is bleak, and there is no foreseeable end to the violence: Despite the positive impacts of many USAID funded prevention programs and the potential positive impact of a fully funded and implemented El Salvador Seguro program, the security situation in El Salvador is bleak. Neither the gangs nor the government is prepared to concede, and further escalation seems likely. Efforts at prevention and rehabilitation, encouraging as they might be, continue to be overshadowed by shocking levels of violence and the bellicose rhetoric of “war” favored by the Salvadoran government. Efforts at creating rehabilitation and reinsertion programs are well intentioned but will fail without adequate financial support from the international community. While the number of homicides may be declining somewhat, the wave of insecurity does not appear to be abating and will continue to pose an immense challenge to the Salvadoran people and their government in 2016.

What is the way forward amidst such violence? We offer two suggestions, neither of which is easy to accomplish. First, some form of dialogue between the government and the gangs is becoming increasingly necessary. A formal negotiation or truce may be unrealistic and politically unpalatable to most Salvadorans, but it is increasingly apparent that the government’s heavy-handed repressive strategies are only producing more casualties and are unlikely to lead to an unconditional surrender by the gangs. Someone within the government has to demonstrate the courage to begin a dialogue that can reduce the violence and open an opportunity for other more constructive approaches to take root.

The more constructive approaches such as working directly in youth prevention and rehabilitation are already included in the government’s Salvador Seguro plan. USAID has been at the forefront of this work, but their efforts and those by members of the Salvadoran government have not been given an opportunity to take root and flourish in high crime areas where the iron fist is the predominate approach. It is time for this type of work to become a priority if El Salvador is to avoid another bloody year like 2015.

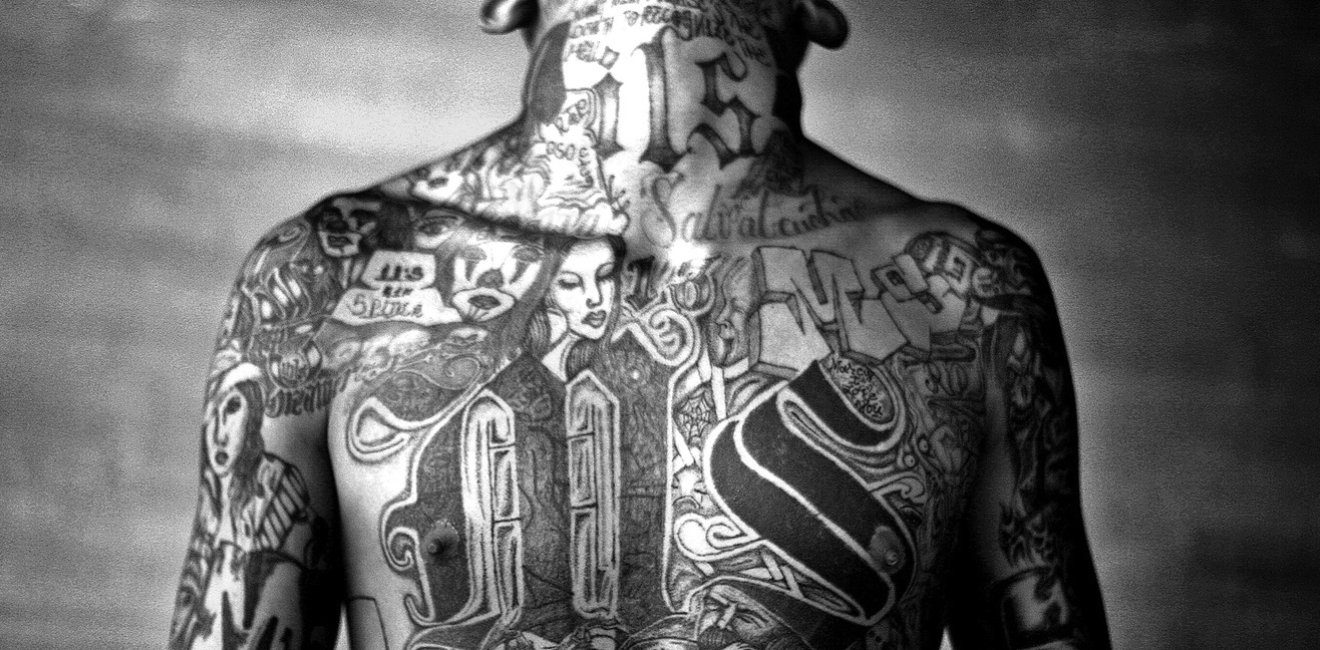

(Sony World Photography Award by markarinafotos is licensed under Creative Commons BY 2.0)

Authors

Director of Policy and Strategic Initiatives, Seattle International Foundation

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Imamoglu’s Arrest Sparks Nationwide Unrest and Raises Fears for Turkish Democracy